Have you ever read a book where someone had pleurisy, or gout, or hysteria, and wondered…how come I never hear about anybody getting that anymore? Well, you’re in luck: It’s Outmoded Diseases Week at LWON, and we’re going to tell you. About some of them, anyway. We’re starting off with neurasthenia, a disease suffered by the famous: Teddy Roosevelt, Virginia Woolf, Marcel Proust, and all three James siblings (Alice made a career of hers).

1867: 53-year-old female, no occupation

1867: 53-year-old female, no occupation

Diagnosis: neurasthenia

Talk very nervous and excitable. Complains of mistiness of vision and palpitations and of general weakness, chiefly of both arms and right leg, right foot is very numb. Does not drag leg when walking. Has been unable to do any work for a year.

The nerves of a neurasthenic are weak, (“-asthenia” meaning incapacity, as in the muscle weakness of myasthenics). That is to say, the nerves are incapable of carrying enough energy, they over-react to the senses, they provide insuffcient motor force. Afflicted patients present with a number of diverse and vague symptoms but in general, have lost control over their sensations, thoughts, impressions, and muscles. This varied but general debility has no physical explanation; it is solely a matter of the body’s inability to function. Neurasthenia is a morbid condition of the brain.

1900: 25-year-old female, husband a laborer

Diagnosis: neurasthenia

Complaint: headache, backache, palpitations, indigestion, shortness of breath, pricking and jumping pains all over. Duration 3 years.

Neurasthenia was named in 1869 by an American neurologist, George Beard, and is treated by specialists in neurology. It occurs in intellectuals with refined nervous systems and in masters of men and captains of industry under great nervous strain and in women whose naturally sensitive nervous systems are burdened with the necessity of reproduction and overwhelmed by education. It has become a fashionable disease and is widely diagnosed, especially among members of the upper classes who consult physicians in private practices. Neurologists working in public charity hospitals also record many neurasthenics among the lower classes.

The neurasthenic patients are advised to take rugged vacations or calm vacations, are treated with rest cures, prescribed nerve tonics, administered electric therapy and hydrotherapy. None of these treatments work except those that do.

1930: 34-year-old male clerk

Diagnosis: neurosis

After the war age 30, patient went back to work as a clerk. Afraid of meeting people. Had to give up work. It was as if he had lost all his power and he could not walk more than fifty yards. After 2 months of bed rest, he felt much better and kept at work about 2 years before he got the next bad attack of nervous exhaustion. He felt immensely tired and used all his spare time and weekends to lie down for rest.

Somewhere around 1930, neurasthenia disappeared; no one was diagnosed neurasthenic any more. Explanations vary. Maybe the neurasthenics themselves disappeared: Freudians say that greater understanding of the unconscious led to more effective psychoanalytic treatments; feminists say that women’s emancipation decreased women’s need to express frustration by getting sick. Or more probably, neurologists, unable to find a physical basis for their patients’ ills, moved the diagnosis from the brain to the psyche, from neurology over to the field of psychology.

And sure enough, according to a study of records of a public hospital in Queen Square, London, the disappearance of the diagnosis of neurasthenia coincided with the appearance of a diagnosis of neurosis. Neurosis was split first into 4 sub-categories, then into 11; and if all sub-categories were added together, the fraction of neurotics was the same as the earlier fraction of neurasthenics.

1934: 59-year-old female, lace cutter

Diagnosis: anxiety neurosis

She feels weak all over and occasionally the use seems to go out of her left foot. Her legs feel numb and heavy and her hands and feet tingle and occasionally ‘go all scarlet.’ Two years ago she had what she described as a ‘stroke.’ She went black and seemed to lose all power in her arms and legs for a few moments. She was completely restored by a little brandy.

So neurasthenia went away but the neurasthenics didn’t. They are variously diagnosed with chronic fatigue, fibromyalgia, post-traumatic stress syndrome, and depression; and are variously treated by psychologists, psychiatrists, rheumatologists, and infectious diseases specialists. The psychiatrist who did the Queen Square study ends her article with a conclusion so obvious and sensible it almost doesn’t need saying. It should nevertheless be written across the top of every science writer’s computer:

- that physicians have always seen patients with vague but related and unexplainable symptoms,

- and that their diagnoses have changed names and have been shifted around various medical fields;

- but the people with these symptoms still have the symptoms,

- and their treatment isn’t much more effective than it was in the 19th century. Sometimes something works, sometimes it doesn’t.

1995: 47-year-old female, university faculty

Diagnoses: depression, chronic fatigue syndrome

Maintains a career of writing and teaching but it completely exhausts her; is unable to drive a car or open a bank account, can hardly cook her own meals; finds social engagement difficult and often asks her husband to break dates for her. Treatment with blood pressure medication and regimen of fast walking is unsuccessful; as is long-term treatment with anti-depressants and psychotherapy. Eventual divorce seemed to help.

_________

Sources: except where otherwise indicated, most of the information, some of the wording, and all-but-one of the case studies came from Death of neurasthenia and its psychological reincarnation by Ruth E. Taylor, published in the British Journal of Psychiatry in 2001. It’s both readable and sensible.

The subject of neurasthenia was also covered last year in Smithsonian, and more recently in The Atlantic. Appropriately, given the subject, those articles and this post are all about different things.

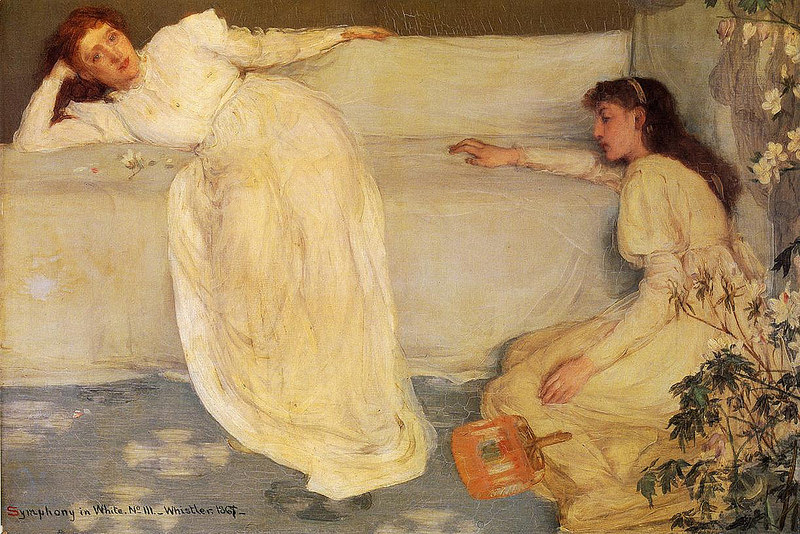

Photo credit: Irina, James Whistler’s Symphony in White, via Flickr

The first time I played the

The first time I played the

HELEN: I like bugs. I started a Ph.D. in ants (and quit, but still think ants are awesome). I have blogged in this space about butterflies. I think the coming of the 17-year-cicadas is one of the most exciting things that happens in the world. My record is quite clear on this: me and bugs, we have no dispute. But I make an exception for camel crickets. They are horrible. Just horrible.

HELEN: I like bugs. I started a Ph.D. in ants (and quit, but still think ants are awesome). I have blogged in this space about butterflies. I think the coming of the 17-year-cicadas is one of the most exciting things that happens in the world. My record is quite clear on this: me and bugs, we have no dispute. But I make an exception for camel crickets. They are horrible. Just horrible.