We’re writers. We like words. We don’t always like writing. Or maybe we just need a little nudge sometimes. Today we’ve collected some of the inspirational (or harassing, or shaming, or whatever works for us) quotes that we have posted around our computers. Maybe some of these will work for you.

We’re writers. We like words. We don’t always like writing. Or maybe we just need a little nudge sometimes. Today we’ve collected some of the inspirational (or harassing, or shaming, or whatever works for us) quotes that we have posted around our computers. Maybe some of these will work for you.

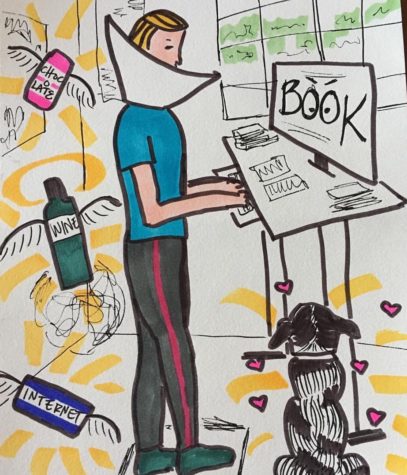

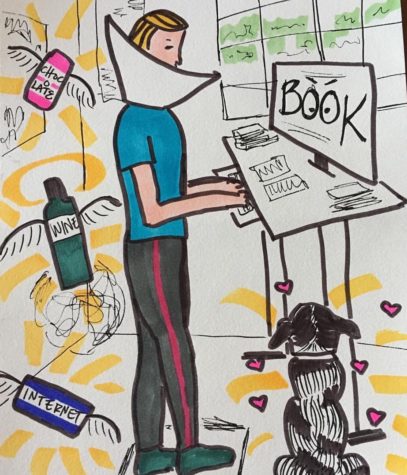

Christie: I am writing a book. Book writing is hard. Some days are harder than others, and for inspiration, I’ve taped a bunch of mantras and words of wisdom to my computer monitor. I’ve stolen most of these from inspiring people.

I am in deep water, but I know how to swim. — From my wise colleague and friend Farai Chideya. (Everyone should read her book on building a career in this changing world.)

Grandiose intentions are the death of getting shit done. — Helen Fields, telling me to stop ruminating already and start writing.

There’s no magic. Really, there isn’t. It’s just one word in front of the other until you’re done. (From a discussion I had with Deborah Blum about book writing.)

I don’t need more time. I need a deadline. This is my “calling myself on my shit” self-talk. Every task balloons to fit the time I’ve given it. Deadlines are how writing gets done.

WTMFA! (Write the motherfucker already!) Some very good advice (based on a Dan Savage saying) that I’ve put on a mug, a whiskey flask and, most recently, my office chalkboard.

Obey the poem’s emerging form! This one was given to me by Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer, whose friend Jack Mueller shouted it to her, with insistent love. I don’t write poetry, but I’ve found that Jack’s words are true for most creative endeavors.

Just one more hill. Here, have a banana. Now keep writing. — Greg Hanscom, my suffer buddy. Continue reading →