This post originally ran in April of 2016. Every dusk, still, the crows fly singly or in groups over my house in Portland, bound west across the Willamette River for their unknown roosting spot. One of these nights I’m going to grab my bike and head after them. Then you’ll probably read about it here. In the meantime, here’s that murdermuration again, along with some of my favorite bird art.

Corvids are a wonderful genre of beast.

I was reminded of this fact not long ago when, biking back home across southeast Portland from the waterfront, a veritable river of crows began streaming overhead. Thousands of them blurred and bobbed and circled each other in a stuttering current from east to west. This current eddied over warehouses. Spilled over parking lots. Formed a recirculation hole over the freeway, then fanned into a delta and out of sight beyond the skyscrapers of downtown. Corvid biologist John Marzluff later told me that the crows were likely heading for a communal roost to settle for the night. There’s one in his home city of Seattle that’s 15,000 strong.

Besides coalescing into this sort of breathtaking “murdermuration,” as I’ve decided to call it, crows recognize their dead, understand analogies, and one species, the New Caledonian crow, even makes its own tools.

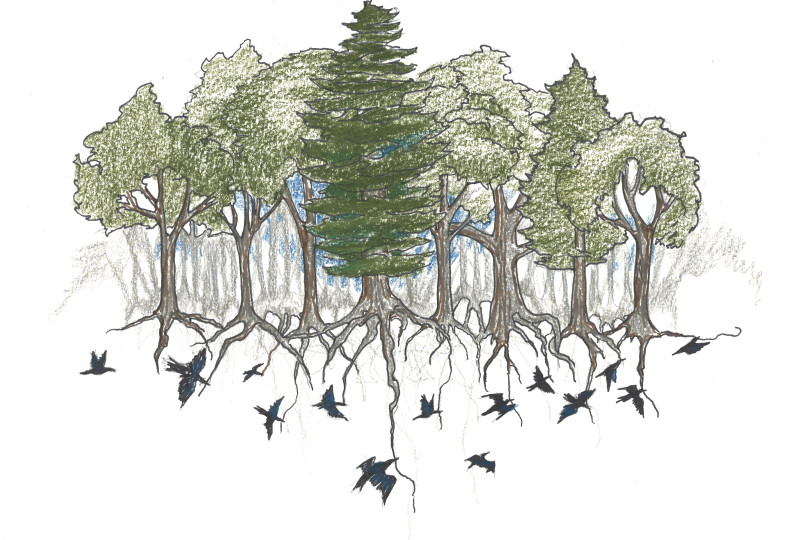

Yet while crows and ravens get most of the attention, smaller members of the corvid family like jays and nutcrackers are out in the world busily building and rebuilding forests. Not on purpose, of course, but through a behavior charmingly called “scatter hoarding,” which basically involves stashing seeds around in various places for later devourment. (The same phrase could easily describe the way I distribute books throughout my house.)

In February, a group of scientists led by Mario Pesendorfer of University of Nebraska, Lincoln published a sweeping review of the available research that elegantly lays out just how important and pervasive this relationship is: Many broadleaf trees, including hickories, oaks, chestnuts and beeches, rely entirely on scatter-hoarders to spread their large, heavy seeds, while 20 percent of pine species do. The authors suggest that this reliance may help some of these species better weather forest fragmentation caused by human activities like farming, or shift their range in the face of climate change.

Unable to walk or fly themselves, in other words, these trees borrow the wings of birds. More…

Christie kicked off the week by reduxing a post about the time she

Christie kicked off the week by reduxing a post about the time she

Can plants behave? Can they weigh risk against reward? Do they have personalities? A new study suggests they can and do—and that we’ve missed their complex behavior in part because they live life at such a different pace.

Can plants behave? Can they weigh risk against reward? Do they have personalities? A new study suggests they can and do—and that we’ve missed their complex behavior in part because they live life at such a different pace.