Hello! It’s been a while. Thanks to the ever-lovely People of LWON for allowing me to revive this tidbit, which I wrote during the early stages of researching my book Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction. That book is now out—fresh this week!—and I’d love for you to give it a look. For now, though, here are a few timeless words from H.G. Wells on the art of science writing.

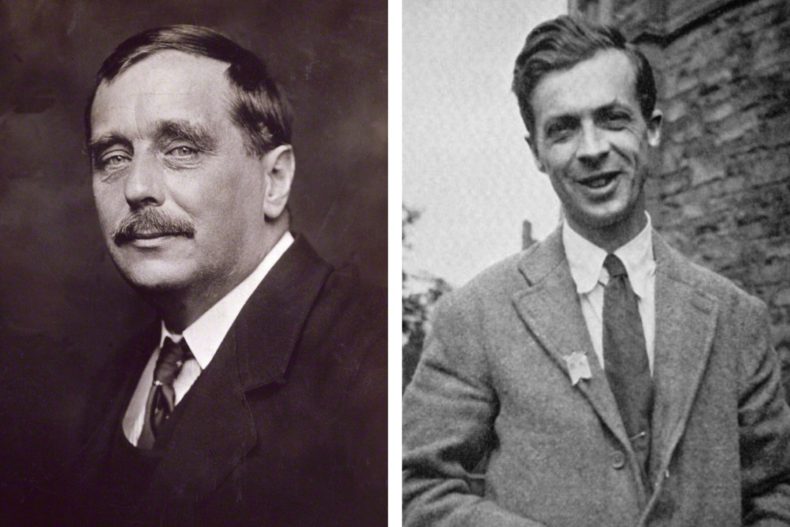

H.G. Wells is remembered today for his science fiction, but he had a solid foundation — and an enduring interest — in science fact. As a university student in London in the 1880s, he was deeply influenced by a course with Thomas Henry Huxley, a biologist so fiercely committed to evolutionary theory that he was known as “Darwin’s bulldog.” In 1926, Wells recruited Huxley’s grandson Julian, also a distinguished biologist, as his collaborator on an encyclopedic project called The Science of Life.

Wells, already famous for The Time Machine, The War of the Worlds, and more than two dozen other novels, had just published The Outline of History, a massively successful work of popular history. Now, with the help of the younger Huxley, he wanted to produce a similar translation of the life sciences, creating what he described as a “real text-book of biology for the reading and use of intelligent people.” Huxley (the elder brother of Aldous, another great writer of speculative fiction) was intrigued by the challenge and by Wells’ nervy intelligence, and he signed up for the job in the spring of 1927.

The trouble began immediately.

“I soon discovered that H.G. demanded every ounce of my knowledge,” Huxley wrote in his memoir, “and called upon a gift I had never fully exerted before — that of synthesizing a multitude of facts into a manageable whole, aware of the trees yet seeing the pattern of the forest, and drawing conclusions which gave the whole work vitality.

“This, I may add, did not come easily.”

Huxley resigned his professorship at Oxford in order to focus on The Science of Life, but Wells was soon impatient with his pace. “I want to urge upon you the need for a steady drive to produce copy and get illustrations ready,” he wrote. A few months later: “You told me in October, did you not, that you were doing 1,000 words a day? Anyhow I think we must get copy in hand faster than this.”

Wells was a taskmaster, but he could be charming, too. During working weekends at his country house, Huxley recalled, Wells spent the days arguing over edits in his distinctively thin, squeaky voice. In the evenings, he entertained his guests with witty stories and made-up games.

By the end of 1928, Huxley had copy — but now, in Wells’ estimation, he had too much copy. “About Book Four,” Wells wrote. “Gip tells me you have at present only a monster of 150,000 words ready. This is hopelessly impossible … a vast undigested mass of stuff is no good at all. What has happened to cause this frightful distention?”

(Huxley admitted that he had been “carried away by my interest in social insects,” and he dutifully shortened the offending volume. It was, he recalled, a “painful operation.”)

Wells, in frustration, finally sent the following note to Huxley:

THOUGHTS IN THE NIGHT

The reader for whom you write

is just as intelligent as you are but

does not possess your store of knowledge,

he is not to be offended by a recital

in technical language of things known to him

(e.g. telling him the position of the heart and lungs and backbone)

He is not a student preparing for

an examination & he does not want to be

encumbered with technical terms,

his sense of literary form & his sense of humor is probably

greater than yours.

Shakespeare, Milton, Plato, Dickens, Meridith, T.H. Huxley,

Darwin wrote for him. None of them are known to have talked

of putting in “popular stuff” & “treating him to pretty bits”

or alluded to matters as being “too complicated to discuss

here.” If they were, they didn’t discuss them there and that

was the end of it.

Sometimes it seems like the writing business has changed beyond recognition in the last 20 years — let alone the last 90. But the only thing that’s changed about the above advice is its pronouns. Don’t dumb it down; don’t assume your writing is required reading. Don’t doubt that your reader is at least as funny, articulate, and intelligent as you are.

Despite Wells’ worries, The Science of Life was completed in 1930. It was a grand success, and Huxley, though exhausted, conceded that he “had learnt a great deal about my own subject, and also, under H.G.’s stern guidance, about the popularization of difficult ideas and recondite facts.” The experience, in fact, launched him on a second career as a public advocate for science and conservation.

Today, The Science of Life is long out of print. But Wells was as prescient about science writing as he was about everything else, and his exasperated counsel still bears repeating.

Images: H.G. Wells in 1920, and Julian Huxley in 1922. Wikimedia Commons.