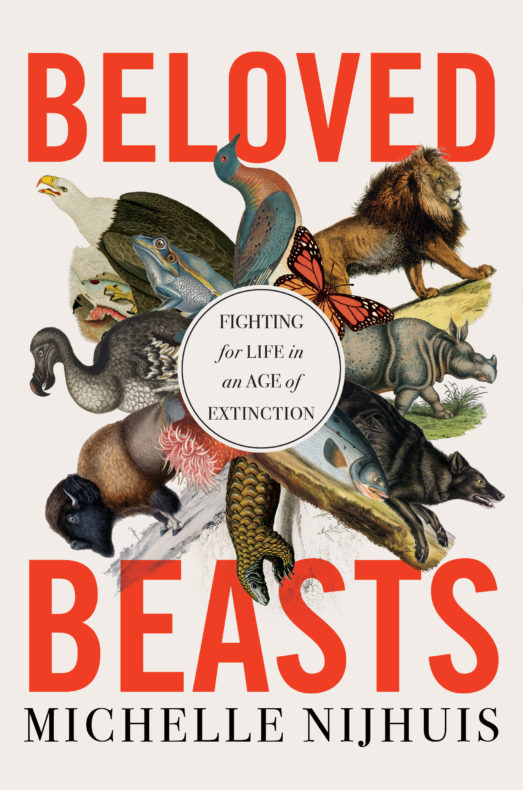

Our Michelle wrote a book! It’s called Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction, and it has already become beloved by the many readers and reviewers who have been talking about it even before the book came out March 9. The book chronicles the history of conservation and conservationists in the U.S., drawing out stories of both the beloved beasts that people have worked to protect and the people behind these efforts, from Aldo Leopold to Rachel Carson to my new favorite, Rosalie Edge, who showed up at a self-congratulatory meeting of the National Association of Audubon Societies in October 1929 to question whether the organization really was protecting birds, or just its own interests. Earlier this month, I got to talk with Michelle about her book, the process of writing it, and how she hopes it will affect how we see conservation. (This interview has been edited and condensed.)

Cameron: I have been thinking you were working on a book—or maybe hoping you were working on a book—ever since your assisted migration story came out in Orion. But then when I started reading about Beloved Beasts, I realized that it was not about tree conservation, but about, well, beloved beasts! (And also the beloved and not-so-beloved and just plain human conservationists who have worked for their protection.) Would you mind talking about how the book came about?

Michelle: I’ve been interested in conservation history for a long time, ever since I was a wildlife biologist myself and witnessed a lot of local political battles over endangered species. I knew there was a historical context to these arguments, and I wanted to learn more about it. But the idea for the book came partly from an LWON post I wrote about a study that tried to estimate the effects of conservation efforts on the status of particular species. I was really struck by that study, because while most people can name off a few individual species that are conservation success stories, we don’t have a systematic sense of what the modern conservation movement has meant for life on earth. I started to wonder whether there was a historical story to be told about what conservation has accomplished as a movement.

Cameron: And the book really does this by following the stories not only of these species, but of the conservationists. Each chapter focuses primarily on one person, but one of the things I loved is how the book keeps returning to the links between these people and their work. It’s almost like the conservationists are part of a conservation ecosystem, and without one, the conservation ecosystem would have looked very different.

Michelle: Yes, I worked to weave together the stories of the some of the iconic figures in conservation—the names we all know—with some that are less known, but equally important. I tried to show that these people knew of each other and influenced each other, and that together they built up the conservation movement. None of them was working in isolation. I did want each chapter to revolve around one or two main characters—that helped me keep the whole thing on track!—and I also wanted each chapter and each character to represent some kind of significant development in the movement. I could have included so much more material about each of the people I wrote about. I spent an afternoon reading Aldo Leopold’s schoolbooks, which were adorable. But one elementary-school anecdote is usually enough!

Cameron: Now I want to see Aldo Leopold’s schoolbooks, too! That was one of the things that really blew me away—how much research went into this book. And historical research, too, when I usually think of you on an adventure with scientists out in the field. What was doing this kind of research like?

Michelle: The research for this book was overwhelming but very fun. I’ve always had a soft spot for context (well, what I call context and what my editors sometimes call “too much background”), and I have this romantic view of archives—I think of them as these stashes of fascinating material that are waiting around for us to discover new things about. So I took on the archival research with a lot of enthusiasm, if not lot of skill. A professional historian would probably be appalled by my methods! I did learn to be much more organized over the course of writing the book. And of course I wasn’t only working with primary materials—I drew from many existing biographies and other studies of the individuals I wrote about.

One of the most joyful parts of the archival work was learning about all these connections between people. Letters from Rachel Carson to Stewart Udall, letters from Rosalie Edge to Aldo Leopold, the affectionate relationship between William Hornaday and Leopold—even though those last two also disagreed on many things. It’s so fun to listen in on these conversations that happened so long ago between these influential people.

Cameron: Did you have one of those moments like in the movies, when you’re in the archives and you find the one piece of information you’ve been looking for and you start jumping up and down until the archivists look at you sternly?

Irma Broun, local conservationist Clayton Hoff, Rosalie Edge, and Maurice Broun at the entrance to Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, circa 1940.

Courtesy of Hawk Mountain Sanctuary

Michelle: I did have a moment when I got a copy of the exchange of letters between Rosalie Edge and Aldo Leopold—these were known to both Leopold’s biographers and Edge’s biographers, but after I got the chance to have lunch with Aldo Leopold’s daughter Estella Junior, who’s now 94, I sent her a copy of them. She’s an admirer of Rosalie Edge, so she was delighted—she wrote back and said, “We can see that Dad was puzzled about this woman!” I loved the idea of Aldo Leopold, who was usually so poised and generally full of Midwestern reserve and niceness, being befuddled by this woman from New York who said whatever she wanted and did whatever she wanted.

Cameron: I think Rosalie Edge was really my favorite character in this, both because I’d never heard of her before and she was so fun to read about, because I never knew what she would do next.

Michelle: One of the fun things about archives is getting to see the paper these people used and getting to see their handwriting. It’s the historian’s equivalent of on-the-ground reporting—you pick up all these details you aren’t aware of at the time. Seeing the hundreds and hundreds of letters Rosalie Edge wrote, where she addressed her friends and enemies in her big, loopy, bold handwriting, gave me such a better sense of her.

Her life and the people who surrounded her made me realize how important the women’s suffrage movement was to conservation. At the time, the conservation movement in the U.S. was mostly made up of wealthy, white male hunters—and they were getting a bit complacent. Edge and many other women had developed their activism skills through the suffrage movement. They came into conservation fired up and said, we have to take on bigger fights. Their work turned conservation into more of a grassroots movement, and into a movement that was bigger and more ambitious.

Cameron: Along with traveling to archives, you also visited a number of other places for this book, from Aldo Leopold’s shack in Wisconsin to community conservation projects in Namibia. How did these experiences add to your writing and your understanding of conservation?

Michelle: I’m a journalist by training, so I always want to be on the scene, even if the scene is 150 years ago—whether that’s standing on top of a buffalo jump, or sitting in an archive and putting my hands on original letters. But I think the place that most affected my thinking was Namibia. My family came with me, and for most of the time we were there we were deep in rural Namibia. Being there made me feel much more committed to ideas that I might have just nodded my head at before: For example, conservationists need to think much more about human behavior and the constructive role people can play in protecting other species. Most people don’t want their local species to go extinct, and they will work to protect them as long as their own basic needs are also taken care of. I understood this, but witnessing it firsthand in Namibia helped me feel it in a much more visceral way.

Cameron: The end of the book draws from the words of past conservationists and those who work in the field today to look forward into the future. Do you feel like what you’ve learned from conservation history has changed where you think the field is headed, and has it shaped what you’re working on now?

Michelle: When I was close to finishing the book I thought, This book has really helped me answer a lot of questions I had about conservation. (And then I thought, Does anyone else have these questions?) Of course, it also raised new questions for me—for example, I’ve continued to think about the success of community-based conservation in Namibia, and I’ve been writing about how it is and can be replicated elsewhere. I’ve been learning more about the relationship between land tenure and conservation: So much of the land that is important for conservation worldwide is managed cooperatively by Indigenous and other rural communities, but very few of these communities have legal rights to their land. Formalizing those land claims is not only a moral good but an effective way to advance conservation, because it allows the conservation work underway to move forward with more certainty.

Cameron: One thing I really appreciated was seeing the daily lives and the mistakes and missteps of many of these renowned conservationists. It just made me feel like they were people, just like me, who could mess up and still do work that has lasting effects today.

Michelle: Yes! That’s one thing I wanted to get across. They are icons now, but they didn’t see themselves as icons. They were just muddling through like the rest of us, trying to protect the places and species they were passionate about. They had no idea whether what they were doing was going to work out—in fact, most of them probably were pretty convinced that it wasn’t going to work out. I think that we can draw inspiration from that, that people in the past felt hopeless at times. They continued to move forward, and so can we.

It’s so easy to get overwhelmed by the daily drumbeat of bad news about the environment. I hope that people take away from the book that humans can play a positive role in conservation. There are huge opportunities for us to do more, and we know what to do—we just need to find the will and the means to do it.