My in-laws are visiting from the East Coast and we’ve had some days to explore. The local bar in our five-hundred-person town is a must-see, its sleek wood and mirrors more than a century old, and the old mountain-mining town of Telluride is forty-five minutes away for window shopping and looking for famous people. The bulk of our days, however, we’ve spent with much older points of interest. If you’re coming all the way from the other side of the continent, I wouldn’t want to be frivolous.

My wife planned most of the tour, a whirlwind of sun-filled valleys and cliffs. The desert of southwest Colorado in October is at its peak, green from summer rains, warm but not searing. We mince our way up canyons, over boulders the size of bedrooms, and follow dry washes and backroads, our truck loaded to take us to the next stop and the next.

A man unlocks a gate near a permanently closed trading post and lets us through. A mile or so down the road, we park under cottonwood shade. Near the outbuildings of a desert ranch, the in-laws spot a boulder across the road pecked with a fifteen-hundred-year old anthropomorph. They’re getting good at spotting images, recognizing the style, Basketmaker Culture.

The boulder is the size of a cottage and it has rock art on every side, bighorn sheep, lightning-like snakes, and human figures with plumes and lines coming out of their heads. We have the usual conversation, surmising headdresses or hunts, a dialogue that has to happen at rock art panels.

I came to this family saunter fresh off of a teaching gig for Crow Canyon Archaeological Center in Cortez, CO. This had been a field program in the Utah backcountry, in the contested and soon to be restored lands of Bears Ears National Monument, just over the horizon from where we live. I taught with an Anglo museum curator, a Hopi archaeologist and tribal member, and a scholar from the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. A dozen participants followed along as we walked to rock art and ruins, which the Hopi archaeologist said were not ruins, not abandoned. They were still on the Hopi map, places very much alive.

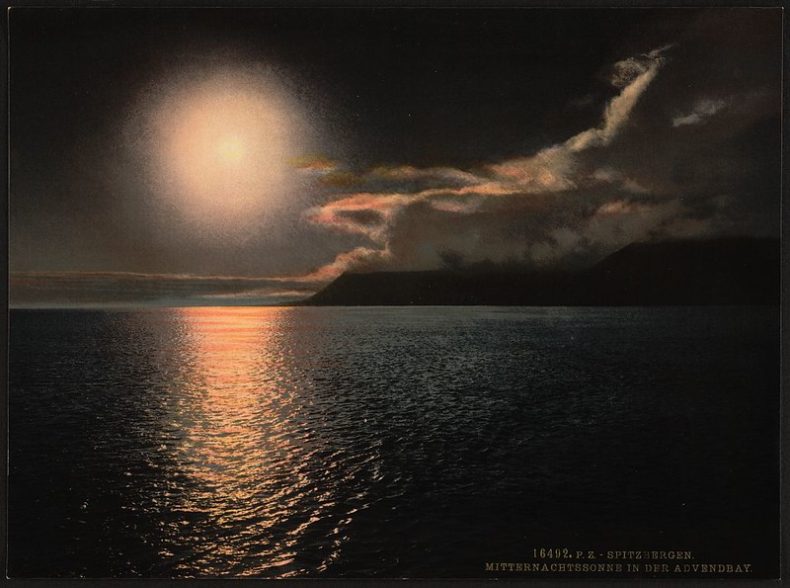

The Hopi archaeologist I taught with would say these petroglyphs were spirit people, ancestors, the ones who carried prayers. I’ve also heard them called personifications of clouds, where instead of seeing a rockface of people, you are seeing thunderheads marching toward you, rain bringers.

Continue reading