This week, I was reading a story from a few years ago about what the last snow on earth might look like. Snow algae, which occur naturally in the snowpack, rise to the surface during the spring; when they emerge, they turn red. This “watermelon snow,” these days, could be seen as a warning. The algae’s presence means the snowpack absorbs more sunlight and melts even faster, allowing even more algae to grow, melting more snow–another of the many tributaries flooding into the rushing feedback loop of climate change.

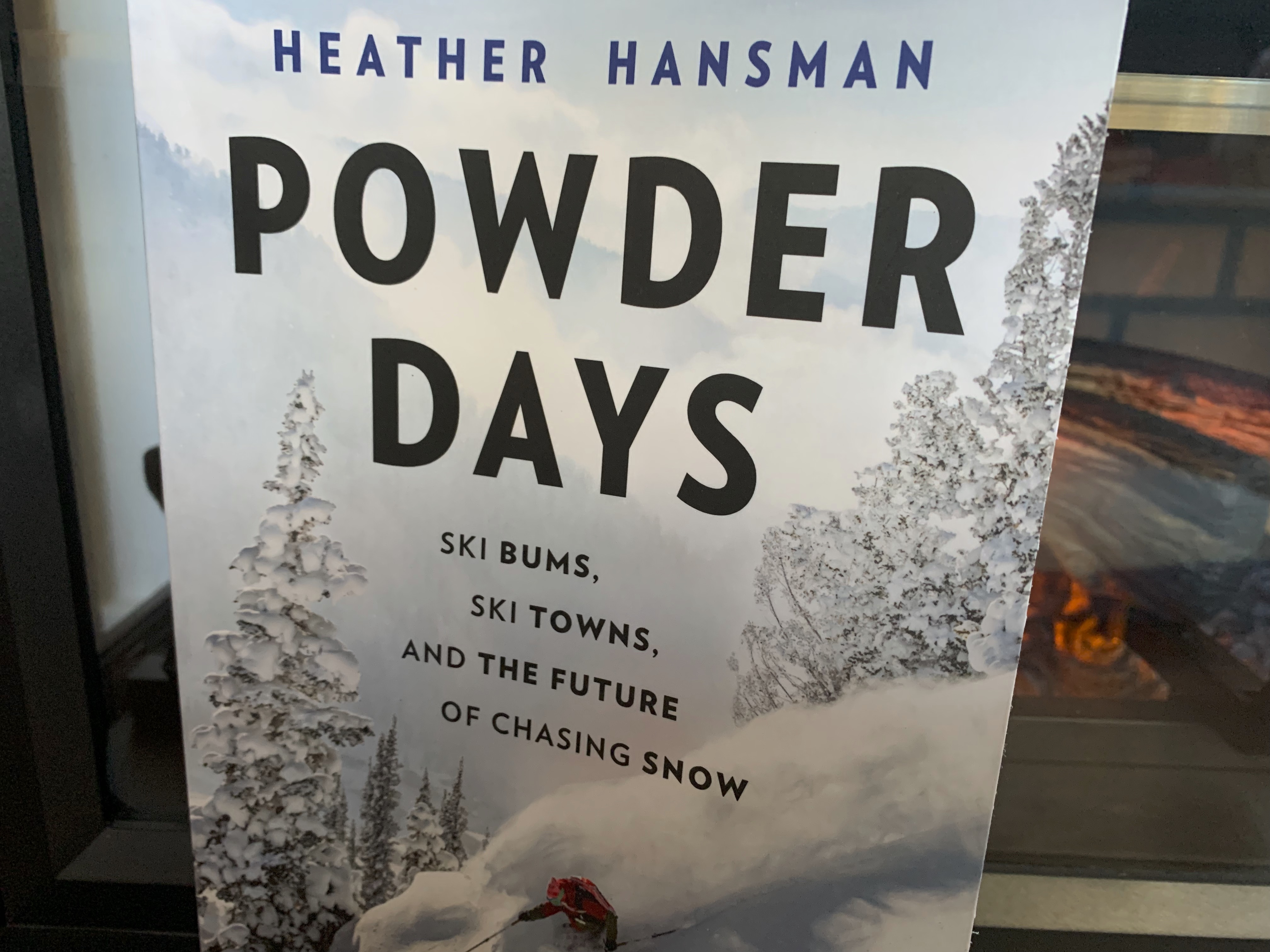

I’ve been thinking a lot about the future of snow, too, while reading Heather Hansman’s Powder Days: Ski Bums, Ski Towns, and the Future of Chasing Snow. The organisms she’s looking at are much bigger, multicellular creatures, yet they live for snow in their own, human way. And in the ecosystems we’ve developed around ski towns, there’s a different feedback loop of low wages, unaffordable housing, class and race issues, and mental health challenges, all against the same backdrop of the rising global temperatures.

There’s also joy. That’s why I picked up this book in the first place—I spent several years in one of these mountain towns, trying to find my way both on the snow and off of it. Even back then, the tension between bliss and tragedy there could make your throat ache. The feeling of floating down an open bowl with only granite peaks and Jeffrey pines looking on. The accidents and avalanches every winter. The connectedness of being part of an unseen river of localism that runs on friendships and favor, on two-dollar Tuesdays and leftovers from your boyfriend’s restaurant job. The constant scramble for a paycheck and a place to live, the relentless waves of tourists, the aggressive hum that takes over the lift lines on a powder day, the unsettling nature of a world that depends on how much snow will fall. And the interior tensions, too. the idea that you’re here, in this most beautiful place, doing what you love–yet somehow, you’re letting it all slip through your fingers with all of this thinking about it, while everyone around you seems to know how to live like this.

And that was then. Now, these problems have grown, and grown more entangled. Hansman, a former editor at Powder and Skiing magazines and former ski bum, set off to find out—is this life even possible anymore?

Continue reading