This post originally appeared on April 15, 2020. I’m republishing it today because 1) I’m deep into editing a book that includes a chapter on Wyoming’s mammal migrations, so mobile elk are top of mind; and 2) bands of elk have begun wandering through the fields near my house in Colorado. I’m not sure where they’re coming from, or where they’re headed, but it’s clearly the season for ungulate movement. If only one of them were satellite-collared…

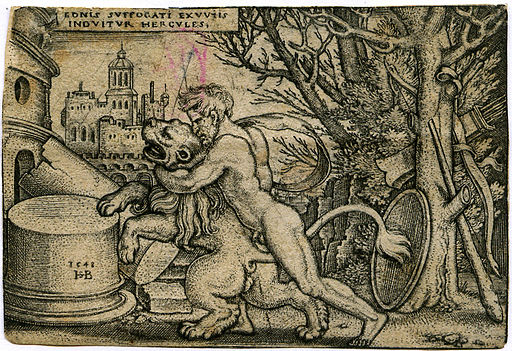

Among my favorite forms of visual art is the wildlife movement map. (Yes, I’m a philistine.) I love the clustered territories formed by rival wolf packs, the filamentous corridors of migratory mule deer, the mystifying circuits of great white sharks. They are, first, aesthetically beautiful, both abstract and intricately structured, like a Jackson Pollock canvas. More than that, they reveal the hidden architecture of the wild world, a cryptic animal infrastructure that whispers across our own paved routes. We might all be homebound and stationary these days, but other creatures remain as wide-ranging as ever.

These maps have become such a staple of wildlife research that it’s easy to forget the sophisticated technology that underpins them. Modern GPS tracking units communicate with orbiting satellites, storing coordinates every few hours — in some cases, every few minutes. Like all tech, these remarkable devices are the products of decades of experimentation, iterative failure, and innovation. Recently I found myself wondering about the animal subjects who participated, unwillingly and unwittingly, in their development. Who was the first creature to wear a satellite collar, and how did it go?

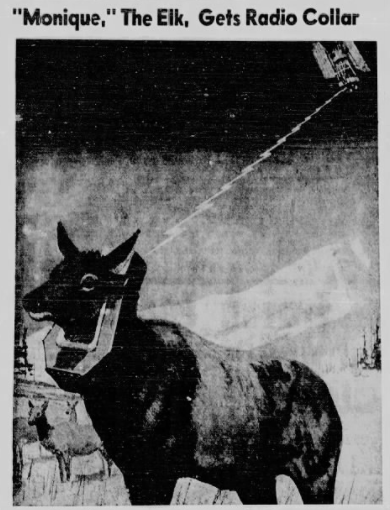

That’s how I became acquainted with Monique the Space Elk.

Really, Monique was two elk, both of whom were outfitted with satellite collars in early 1970 — almost fifty years ago on the dot, in fact. The Moniques belonged to a migratory herd of 7,000 animals that wintered on the National Elk Refuge just south of Yellowstone National Park, and then went… well, no one quite knew where. Although John and Frank Craighead, twin brothers and legendary wildlife researchers, had long studied the region’s elk movements, their tracking methods were rudimentary. In the 1960s they’d fitted thousands of animals with color-coded necklaces, then hiked around Yellowstone searching for their bands. The herculean project revealed patches of habitat, but offered scant insight into how the animals moved between them — a Connect-the-Dots illustration with no dots connected.

Those gaps, the Craigheads vowed, would be filled in 1970. The previous year, they’d struck up a partnership with NASA to develop a newfangled elk tracking collar that would communicate with a weather satellite called the Nimbus 3. The collar cost $25,000, weighed 23 pounds — most of it a sheath of protective fiberglass — and would beam its wearer’s location and skin temperature, along with the ambient air temperature and light conditions, to the Nimbus every day.

A new era of wildlife biology had dawned. “The beauty of the experiment,” John Craighead told reporters in February 1970, “is that we can daily monitor elk at distant or remote locations where it might be impossible to go into the field and visually watch her.”

That information, Craighead added, wasn’t merely academic. The environmental movement was ascendant, the inaugural Earth Day just two months away. Satellite gathering, Craighead said, was “one of many research tools that scientists need if man is to prevent further global pollution of air and water and destruction of plant and animal life.” The Space Elk wouldn’t just carry a collar that weighed as much as a Boston terrier — she would bear the burden of planetary salvation.

Continue reading