This post first appeared in 2012, when I was full of enthusiasm for seed catalogs and tomatoes. Now, my tomatoes are full of enthusiasm, too. A volunteer that sprung up in a planter with succulents in it has now been growing strong since last year, bursting with tomatoes even through the winter. What kind is it? No idea. Maybe I should call it “Happy.”

I can’t remember why the seed catalogs started showing up, but once they did, I was a goner. If you haven’t ever gotten one, imagine full color photo spreads of produce, like the striped Tigger Melon and and the orange-red lusciousness of the French pumpkin Rouge Vif d’Etampes. I suppose the names don’t have quite the ring of “Miss September,” but compared to some centerfold beauty, these fruits and vegetables are much more alluring — maybe because some September, a new variety might appear in my own garden, one that I could give any name I wanted.

This is how I ended up with at least six different varieties of tomato seeds last year. I’m not quite sure what it is about tomatoes. Even before I had a real garden, I’d buy the plants every year. They always seemed so hopeful, appearing in the nursery in winter, when you can’t even imagine that by fall you’ll be saying ridiculous things like, “Caprese salad, again? I don’t think I can do it.”

Somewhere along the lines, I realized there were more options out there then the plants we could find at our local nursery. I knew I had to grow from seed once I learned that there was a variety named after the writer Michael Pollan. I could even figure out how to crossbreed my own tomatoes (and wondered what I’d call a Black & Brown Boar crossed with a Pink Berkeley Tie-Dye–oh, the possibilities!).

So there I found myself, one morning last winter, in front of a tray of dirt with seeds and Sharpies and labels in hand.

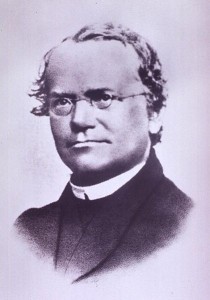

As I planted, I got to thinking about Gregor Mendel and his pea experiments. I’d first learned about them in high school, when the charts showing tall and dwarf pea plants, yellow and green peas, made it all seem so easy. But with seeds in hand, I started to buckle under the logistics. To do anything, first these seeds would have to grow.

Even if they did, I’d then have to do some tricky tweezer work (I read a bit about crossing tomatoes here). Then the tomatoes would have to grow, produce seeds. I’d have to save the seeds, grow the first generation the next winter, and do it all over again. If I was lucky, I’d start seeing crazy new phenotypes two summers from now.

That’s what Brad Gates does. At Wild Boar Farms (the California farm where I bought many of my seeds), he grows and tends thousands of plants each year, always keeping an eye out for novel tomatoes. (Brad’s Black Heart was a result of a random mutation that he spotted).

Gates used to ship some of his seeds off to the Southern Hemisphere, so he could grow two generations of tomatoes and try to speed through the breeding process. But he was never sure what was happening with his tomatoes, if someone was choosing exactly what he would.

Even though I’ll never know exactly what Mendel was thinking every day, when he went out to tend his peas (although Robin Marantz Henig’s A Monk and Two Peas gave me a good idea), but I did ask Gates. When it comes to growing tomatoes, he said,“the fun part is all the Christmas presents I get to open every year,” he said, Whether it’s new flavors, textures, shapes, and sizes—“there are hundreds of surprises.”

And as my tomatoes began to grow, I started to get it. Every day, I watched my little plants unfold. Maybe it’s crazy that I had to set up hundreds of seeds to finally take the time to watch something grow. My curiosity about my future tomatoes grew each day—but at the same time, so did my patience.

What happened next shouldn’t really have surprised someone who once required a hazmat team to descend on her freshman chemistry lab (mercury spill from carelessly placed thermometer). When I set the starts out for hardening, a spring windstorm set all the labels flying. Then friends started to pick up some of my extra seedlings (I couldn’t fit all 144 in our raised beds). By the time I planted, I had a vague idea of which one was which, but then old tomatillos grew up among them and everything became a tangled mass of vine. Even the seeds I tried to save once the season was done got thrown out by accident.

Winter is here again, and so are my seed catalogs. I don’t think I will discover anything that hasn’t already been grown, and it’s unlikely that I will create a variety that will someday lure gardeners from between the pages of a seed catalog. But I do have a new respect for genetics, and for farmers. And I’ve certainly learned one thing already: Michael Pollan is delicious.

__________

Photo credits: Thamizhpparithi Maari, Goldlocki, Wikimedia Commons