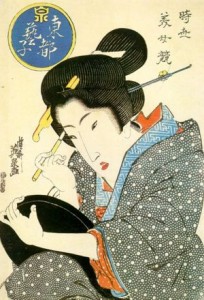

In 18th century Japan, samurai women modeled themselves after the great beauties of the day. Like courtesans and geishas, they turned their faces into artists’ canvases, concealing their skins beneath a thick white paste. Then they applied the paint–thin charcoal lines for eyebrows, delicate crimson for mouths, and a dark black tint for their teeth. All this artifice, all this feminine allure came at a steep price, however. This week, Japanese researchers revealed that high levels of lead in ancient cosmetics likely poisoned generations of samurai children.

In 18th century Japan, samurai women modeled themselves after the great beauties of the day. Like courtesans and geishas, they turned their faces into artists’ canvases, concealing their skins beneath a thick white paste. Then they applied the paint–thin charcoal lines for eyebrows, delicate crimson for mouths, and a dark black tint for their teeth. All this artifice, all this feminine allure came at a steep price, however. This week, Japanese researchers revealed that high levels of lead in ancient cosmetics likely poisoned generations of samurai children.

The Japanese team, led by Tamiji Nakashima, an anatomist at the University of Occupational and Environmental Health in Kitakyushu, Japan, became suspicious of the women’s makeup after testing skeletal remains from the Edo period ( A.D. 1603 to 1867). Skeletons from the samurai class contained surprisingly high levels of lead, far higher than that found among fishers and farmers in the lower classes. Moreover samurai women were twice as contaminated as samurai men.

Puzzled, Nakashima and his colleagues began searching for the source. Historical accounts showed that the white foundation paste so loved by samurai women contained white lead. Brushing it on to their skins and inhaling paste particles, the women slowly poisoned themselves and unwittingly passed on the contaminant to their nursing babies. As a result, some young samurai children possessed enough lead in their systems to cause severe developmental disabilities.

Could something similar happen today? Out of curiosity, I decided to check with the Campaign for Safe Cosmetics. Continue reading