Metastable: Down the block, along the street, is a steep bank on which trees have taken root and grown, slanting off the bank and over the road, balancing their holds in the ground with increasing height and occasional high winds and of course gravity. One day sooner or later a good rain slightly liquifies the soil, the wind catches the leaves and branches, gravity (which always wins) wins again, and a tree drops like a rock. What had seemed stable was not. It was metastable and had been all along. Continue reading

Metastable: Down the block, along the street, is a steep bank on which trees have taken root and grown, slanting off the bank and over the road, balancing their holds in the ground with increasing height and occasional high winds and of course gravity. One day sooner or later a good rain slightly liquifies the soil, the wind catches the leaves and branches, gravity (which always wins) wins again, and a tree drops like a rock. What had seemed stable was not. It was metastable and had been all along. Continue reading

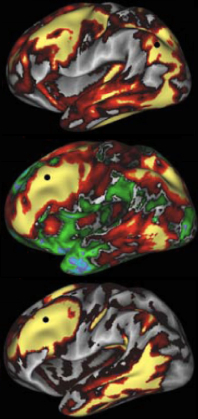

In the mid-1990s, neuroscientist Marcus Raichle noticed something funny going on in some of his brain-scanning experiments.

In the mid-1990s, neuroscientist Marcus Raichle noticed something funny going on in some of his brain-scanning experiments.

Here’s what usually happens, more or less: someone lies inside of the scanner and performs a specific task, like pressing a button. In response to that particular task, some parts of the brain become more active. Voilà: you have identified the regions involved in button-pressing.

But Raichle observed that a couple of areas actually quiet down during a goal-directed task—during many different tasks, in fact. One of these spots is in the parietal lobe, in the middle of the back of the brain. Raichle thought the data was curious, but didn’t dwell on it. He threw the scans into a folder, labeled it MMPA—for ‘medial mystery parietal area’—and filed it away.

Continue reading

Last fall, ninth-grader Jordan McFarland received a jab of seasonal flu vaccine and the vaccine to prevent pandemic H1N1 virus. The next day, he got a bad headache and the chills. His muscles began to spasm and shake. He couldn’t walk. One of the people working at Jordan’s after-school daycare called 911. He was diagnosed with Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), a rare disorder that occurs when the body’s immune system attacks nerve cells.

Last fall, ninth-grader Jordan McFarland received a jab of seasonal flu vaccine and the vaccine to prevent pandemic H1N1 virus. The next day, he got a bad headache and the chills. His muscles began to spasm and shake. He couldn’t walk. One of the people working at Jordan’s after-school daycare called 911. He was diagnosed with Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), a rare disorder that occurs when the body’s immune system attacks nerve cells.

In the US, about 3,000 to 6,000 people contract GBS each year. No one knows exactly what causes the illness, but infections appear to play some role. In Jordan’s case, his parents blame the vaccine. “There is no doubt in my mind that Jordan got GBS from his swine flu shot,” said Arlene Connin, Jordan’s stepmother.

And who could blame Connin? Less than 24 hours after receiving a flu shot, Jordan was writhing around on a hospital bed, unable to control his muscles. “It was so shocking and scary for everyone, because we didn’t know what was going on,” she said. But Connin had one more reason to suspect a link.

May we take a moment of your time to introduce Cassandra Willyard? She explained once that the reason she needed to ride around in police cars was to write about why Baltimore was HIV heaven, a logic that’s not immediately obvious. Click on About for more about Cassandra, and then go find her website to see the connection between infectious disease, urban decay, poverty, and the decline of civilization. Somehow she’s still not depressing at all, and we’re delighted she’s around. Her first post will be tomorrow morning.

May we take a moment of your time to introduce Cassandra Willyard? She explained once that the reason she needed to ride around in police cars was to write about why Baltimore was HIV heaven, a logic that’s not immediately obvious. Click on About for more about Cassandra, and then go find her website to see the connection between infectious disease, urban decay, poverty, and the decline of civilization. Somehow she’s still not depressing at all, and we’re delighted she’s around. Her first post will be tomorrow morning.

Photo credit: Baltimore under clouds, Mark Peters

An old Yiddish joke: A poor yeshiva student visits a local family every evening for dinner. Each night, the family serves him potatoes: boiled potatoes, fried potatoes, potato soup, potato pancakes, potato kugel, and so on. After a week or two of this splendid spud-fest, the student asks his hosts to tell him the correct blessing over potatoes. “What?!” they reply. “You, a yeshiva student, don’t know the blessing for vegetables that grow in the ground?” “Of course I do,” he replies. “But what do I say when they are coming out of my ears?”

I thought of this joke when I read about Chris Voigt’s “20 Potatoes a Day Diet,” which I read about on that excellent web site, potatoes.com. Voigt, the executive director of the Washington State Potato Commission, aims to prove that he can remain healthy while eating nothing but potatoes and potato products for 60 days, starting October 1.

A few days ago, while idly surfing the net, I stumbled upon a photograph that seemed to come from another world, a place much more surreal and interesting than the one I inhabit. The photo in question showed a traditional fighting shield from highlands of Papua New Guinea. But it wasn’t the shield that caught my attention. It was the artwork. The maker had painted the Phantom on it, a comic-strip character created in the 1930s by American artist Lee Falk. And the superhero on the shield clearly meant business. He held an axe in one hand, a revolver in the other.

A few days ago, while idly surfing the net, I stumbled upon a photograph that seemed to come from another world, a place much more surreal and interesting than the one I inhabit. The photo in question showed a traditional fighting shield from highlands of Papua New Guinea. But it wasn’t the shield that caught my attention. It was the artwork. The maker had painted the Phantom on it, a comic-strip character created in the 1930s by American artist Lee Falk. And the superhero on the shield clearly meant business. He held an axe in one hand, a revolver in the other.

The idea of the Phantom fighting off evil in Papua New Guinea fascinated me, so I began digging around, trying to piece together the anthropological backstory. I was pretty certain there was one.

And I was right. Continue reading

At 5:04 p.m. on October 17, 1989, two decades after he served as a combat soldier in Vietnam, Lance Johnson felt the tremors of San Francisco’s Loma Prieta Earthquake from his apartment in Marin County. He took his cup of coffee to the couch, switched on the news and saw a live feed of the fire and destruction happening 40 miles south. Suddenly, he was hit with some of the common symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). As he recalls: Someone tripped a switch in my head, and instantly, I was back in Vietnam. In my mind, the concept of time suddenly meant nothing, and I traveled a wormhole in space from San Francisco to twenty years earlier in Southeast Asia. Panic. I didn’t know what to do.*

At 5:04 p.m. on October 17, 1989, two decades after he served as a combat soldier in Vietnam, Lance Johnson felt the tremors of San Francisco’s Loma Prieta Earthquake from his apartment in Marin County. He took his cup of coffee to the couch, switched on the news and saw a live feed of the fire and destruction happening 40 miles south. Suddenly, he was hit with some of the common symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). As he recalls: Someone tripped a switch in my head, and instantly, I was back in Vietnam. In my mind, the concept of time suddenly meant nothing, and I traveled a wormhole in space from San Francisco to twenty years earlier in Southeast Asia. Panic. I didn’t know what to do.*

You don’t have to be a combat vet to know that your response to stress—whether a loud noise, dying relative or looming deadline—changes over time. After the first exposure, we are somehow primed for the next, even weeks or years later. And when something in that process goes wrong, the consequences can be tragic.

Neuroscientists don’t understand much about how the brain encodes such a versatile stress response. It’s part of a complicated mess of hormonal, chemical and electrical signals in a brain system called the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. A new rat study has made the picture slightly less muddled, opening the door a tiny bit to new treatments for PTSD and other types of chronic stress.

( “People of Last Word on Nothing” doesn’t sound as exciting as People of LWON.) We are pleased and proud to introduce Virginia Hughes. One of her early stories was about why Hagia Sophia doesn’t fall down in earthquakes, which was impressive because not just anyone can get you interested in the structural loads of cathedrals. She introduces herself if you click About, and explains her Myers-Briggs personality on her own website. We are so very happy she’s here. Her first post: tomorrow morning.

“People of Last Word on Nothing” doesn’t sound as exciting as People of LWON.) We are pleased and proud to introduce Virginia Hughes. One of her early stories was about why Hagia Sophia doesn’t fall down in earthquakes, which was impressive because not just anyone can get you interested in the structural loads of cathedrals. She introduces herself if you click About, and explains her Myers-Briggs personality on her own website. We are so very happy she’s here. Her first post: tomorrow morning.

Photo credit: Hagia Sophia, Radomil