I haven’t had anything to do with biology since I wrote an article years ago about sleeping pills. I found out that the drugs used by 60-gazillion insomniacs to put themselves to sleep are not the chemicals the brain uses to put us to sleep naturally. Can’t neuroscientists just find those brain chemicals and sell them to us? I called and asked; the answer is not that neuroscientists can’t find the chemicals, but that they find way, way too many. Not only that, but each chemical seems also to affect some different and important part of the body: the immune system, the body’s clock, digestion, blood pressure. I was indignant: all those causes for just one effect, and each cause having other effects? What ever happened to the principle of parsimony? I gave up on biology and ever since, have stuck closely to astronomy: the laws of the universe are parsimonious. Continue reading

I haven’t had anything to do with biology since I wrote an article years ago about sleeping pills. I found out that the drugs used by 60-gazillion insomniacs to put themselves to sleep are not the chemicals the brain uses to put us to sleep naturally. Can’t neuroscientists just find those brain chemicals and sell them to us? I called and asked; the answer is not that neuroscientists can’t find the chemicals, but that they find way, way too many. Not only that, but each chemical seems also to affect some different and important part of the body: the immune system, the body’s clock, digestion, blood pressure. I was indignant: all those causes for just one effect, and each cause having other effects? What ever happened to the principle of parsimony? I gave up on biology and ever since, have stuck closely to astronomy: the laws of the universe are parsimonious. Continue reading

This story is so kooky that I must lead with the video:

This slow-motion film stars turkeys of different ages, from hatchlings to adults, and yes, they’re furiously climbing a steep wooden ramp. The video comes from a study published earlier this month. But let me start at the beginning.

Continue reading

This one’s going to take a little explanation. Maxwell was James Clerk Maxwell, famous 19th century physicist. He made up his demon as a way around a then-new and depressing law of physics, the Second Law of Thermodynamics. The Second Law said that when things are left alone and nothing’s done to them, hot things always become cold, but cold things never heat up. The reason this is depressing is because the Second Law, if it ran on long enough, would end in what 19th century physicists called the heat death of the universe.

Anyway, Maxwell thought if he had a container divided into two rooms, one hot and one cold, and a door between the rooms, then a smart little demon could stand at the door and let the cold flow into the hot room but not the heat into the cold room, and thus thwart the Second Law. He couldn’t do it and generations of physicists since have agreed it couldn’t be done. Looks like the universe is stuck with the heat death, the death of heat. I don’t know why Abstruse Goose is so cheery about it.

When I first saw the magical, Harry-Potter-like images taken by the folks at the Nottingham Caves Survey in England, my jaw clunked on my desk. Archaeologists have enthused for some time now over the potential of laser scanning for recording ancient sites, but until now the results looked merely brisk and workmanlike. But these new 3-D pictures of the secret subterranean world beneath the ancient city of Nottingham are taking this work to a whole new level. These images–like the one above of a secret 14th century passageway leading to Nottingham Castle–resemble works of surrealism and fantasy. But they are pure science.

First, a quick word about Nottingham. Continue reading

I’m riddled with anxieties and have no faith whatever. My book is dopey and nobody’s reading it and I have no ideas for another one. Print publishing is dying anyway. And the deader it gets, the less likely it is to publish anything I write, even if I did have an idea. I could take care of these anxieties with some nice pills, but I thought I’d try a calming statistical assessment first. Science, of course, excels at such assessments and what I really admire is when it steels its nerves, narrows its eyes, and assesses its own work. “We’ve found an exoplanet and it’s at the 2-sigma level,” they say, while they silently try to radiate confidence. Continue reading

I’m riddled with anxieties and have no faith whatever. My book is dopey and nobody’s reading it and I have no ideas for another one. Print publishing is dying anyway. And the deader it gets, the less likely it is to publish anything I write, even if I did have an idea. I could take care of these anxieties with some nice pills, but I thought I’d try a calming statistical assessment first. Science, of course, excels at such assessments and what I really admire is when it steels its nerves, narrows its eyes, and assesses its own work. “We’ve found an exoplanet and it’s at the 2-sigma level,” they say, while they silently try to radiate confidence. Continue reading

Did the prehistoric equivalent of a great big, beery, boozy party give rise to some of the world’s earliest civilizations? That sounds about as likely as Sarah Palin rolling up her sleeves and deciphering the Dead Sea Scrolls. And yet, that idea–beer as one of the original jet fuels of civilization–is gathering momentum among archaeologists, and not just when they are in their cups. Continue reading

Did the prehistoric equivalent of a great big, beery, boozy party give rise to some of the world’s earliest civilizations? That sounds about as likely as Sarah Palin rolling up her sleeves and deciphering the Dead Sea Scrolls. And yet, that idea–beer as one of the original jet fuels of civilization–is gathering momentum among archaeologists, and not just when they are in their cups. Continue reading

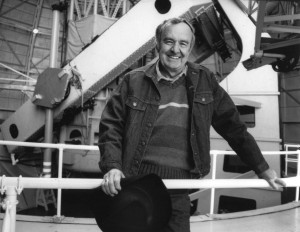

This has been a bad year for contrarian cosmology. First Geoffrey Burbidge died, at the age of 84, on January 26. And now comes the news that Allan Sandage, also 84, died last Saturday.

I’ll let other obituaries explore Sandage’s monumental scientific biography at length and in depth: apprenticing under Edwin Hubble; assuming Hubble’s observing program after his death in 1953; recalibrating the distances to galaxies and, therefore, the scale and age of the universe; compiling the Hubble Atlas of Galaxies; making the first observation of a quasar; collaborating on a paper positing the formation process of the Milky Way. He was the last of the lone astronomers, those gods of Mounts Wilson and Palomar, doing daily battle with the abyss. Sandage once defined cosmology as “the search for two numbers”—the current rate of the expansion of the universe, and how much that rate is changing over time. Know those numbers, he declared, and you would know the alpha and the omega of the universe: its age and its fate.

For me, though, his death also brings to mind a quieter, less celebratory subject that has nagged at me for years: the relationship between individual psychology and the scientific method.

Cameras are nifty. They take a slice of the hustle and bustle of real life and dip it in liquid nitrogen, preserving it for eternity (or as long as our hard drives last). But they can’t do everything. Try taking a picture of the moon or the stars or a particularly lovely sunset. If you’re an amateur like me, you know that too often the image you see with your eyes doesn’t match the image you capture. It’s frustrating. Continue reading