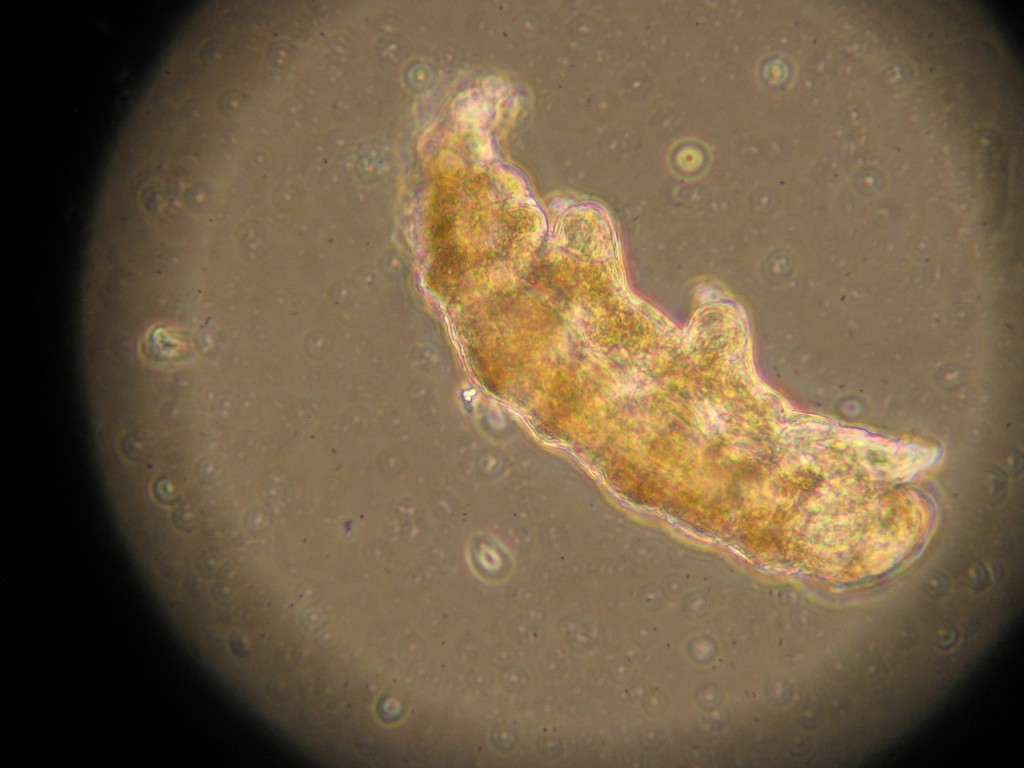

When I first saw the magical, Harry-Potter-like images taken by the folks at the Nottingham Caves Survey in England, my jaw clunked on my desk. Archaeologists have enthused for some time now over the potential of laser scanning for recording ancient sites, but until now the results looked merely brisk and workmanlike. But these new 3-D pictures of the secret subterranean world beneath the ancient city of Nottingham are taking this work to a whole new level. These images–like the one above of a secret 14th century passageway leading to Nottingham Castle–resemble works of surrealism and fantasy. But they are pure science.

First, a quick word about Nottingham. Continue reading