The latest alien planets hit the news like fireworks, I write about them a lot, and I’ve always found them boring. I’d been convinced early on by an eminent astronomer who said flatly that finding extra-solar planets wasn’t, as he said, interesting. In the first place, observations were nearly impossible and decades of claims turned out to be mistaken. In the second, stars could have planets, obviously, ours did; exoplanets were neither a surprise nor a clue to how the universe worked. In the mid-1980’s, a dedicated planet hunter told his interviewer he was too embarrassed to admit he looked for exoplanets so he kept it secret and fudged proposals for telescope time by saying he was looking for failed stars. So in the past months, the excitable press releases and news stories about this and that new planet? I say, pish. Turns out I’m wrong.

The latest alien planets hit the news like fireworks, I write about them a lot, and I’ve always found them boring. I’d been convinced early on by an eminent astronomer who said flatly that finding extra-solar planets wasn’t, as he said, interesting. In the first place, observations were nearly impossible and decades of claims turned out to be mistaken. In the second, stars could have planets, obviously, ours did; exoplanets were neither a surprise nor a clue to how the universe worked. In the mid-1980’s, a dedicated planet hunter told his interviewer he was too embarrassed to admit he looked for exoplanets so he kept it secret and fudged proposals for telescope time by saying he was looking for failed stars. So in the past months, the excitable press releases and news stories about this and that new planet? I say, pish. Turns out I’m wrong.

The news comes mostly from one satellite called Kepler, which looked through 156,453 stars and found 1,235 things that looked like planets. If you’re more convinced by large numbers than small — and you should be — and even if most of them turn out not to be planets, then Kepler is pretty convincing. Kepler is interesting too, but less because it’s finding other earths that have life and that we can go and visit: it hasn’t and we can’t. And besides, we already know planets can have life. Kepler’s planets are interesting because they’re some of the first real evidence for how planets form and what solar systems look like.

Before anybody had real data, the leading theory for planet formation hadn’t strayed too far out of the 18th century. And theorists thought solar systems would probably, to first order, look like ours: a nice orderly star orbited at a discrete distance by smallish rocky planets and farther out, by big fluffy planets, all going the same direction and aligned in the same flat plane. These new planetary systems — not all of them via Kepler — look like all hell. Continue reading →

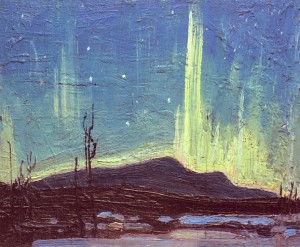

One could spend a great deal of time working out exactly what characteristics unite the various Persons of LWON. (Most Readers of LWON, we cheerfully assume, have more pressing projects to hand.) Our newest LWON-ian, Jessa Gamble, proves emphatically that the link isn’t geographical, by living far enough north that most of us would require a polar reporting fellowship to visit. She spends her time in Yellowknife writing with humor, insight and gently removed grace about, among other things, northern lands, southwestern languages and that most delightful of human pursuits, sleep. Her first post is Wednesday morning, and we think you’ll like her very much.

One could spend a great deal of time working out exactly what characteristics unite the various Persons of LWON. (Most Readers of LWON, we cheerfully assume, have more pressing projects to hand.) Our newest LWON-ian, Jessa Gamble, proves emphatically that the link isn’t geographical, by living far enough north that most of us would require a polar reporting fellowship to visit. She spends her time in Yellowknife writing with humor, insight and gently removed grace about, among other things, northern lands, southwestern languages and that most delightful of human pursuits, sleep. Her first post is Wednesday morning, and we think you’ll like her very much.