You understand the joke, right? that high-energy physics learns the nature of subatomic particles by hurling them at other subatomic particles and when the particles collide, studying the debris? So this is funny.

Also disturbing.

You understand the joke, right? that high-energy physics learns the nature of subatomic particles by hurling them at other subatomic particles and when the particles collide, studying the debris? So this is funny.

Also disturbing.

“Dear Mr. Hayden. You are going to hell. I write this not to gloat, but as a warning. Those who do the devil’s work reap Satan’s wages.”

“Dear Mr. Hayden. You are going to hell. I write this not to gloat, but as a warning. Those who do the devil’s work reap Satan’s wages.”

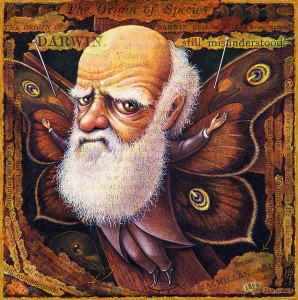

Is it wrong that I enjoy getting anti-evolution reader mail? It happens to anyone who writes about evolution, and I’ve always found it somehow charming. It’s just so darned flat-earthy. Plus, the no-evolution absolutists are usually less obnoxious than the climate change deniers, even when discussing eternal damnation. And some—though not all, by a long shot—even mange to be more coherent than the “Einstein was wrong, I can prove it” set. (I should rush to point out that he wasn’t, and they can’t.)

“Have chimps in zoos shown any signs of evolving? I checked with our zoo, they said, as a matter of fact they no longer have their evolution tour. Why did sexual reproduction evolve when it isn’t the most effective mode of reproducing? Why did a redwood tree evolve into a citrus tree? What was the survival benefit? Your article was nothing but wordiness.”

The wordiness I’ll cop to. Still, there’s something sad at the heart of these evolution wars. Charles Darwin was by all accounts a very decent fellow, but evolution-deniers always want to paint him as some sort of cosmic scoundrel. It makes me feel bad for the old guy that he should have to face so many posthumous slings and arrows. Maybe that’s why it feels right to offer him a birthday tribute two days late this year, and in the words of some of the hundreds of readers who have written to protest my evolution articles over the years. St. Valentine was a martyr too, after all. Continue reading

At first glance, the prison camp at Guantánamo Bay doesn’t seem like much of a subject for archaeologists. The controversial camp, built to detain suspected terrorists after the 2001 attack on the World Trade Center, seems far too new, far too contemporary for archaeological research. And if that weren’t reason enough to steer clear, Gitmo remains firmly out-of-bounds to nearly everyone, a terra incognita behind barbed wire on an American naval base in Cuba.

At first glance, the prison camp at Guantánamo Bay doesn’t seem like much of a subject for archaeologists. The controversial camp, built to detain suspected terrorists after the 2001 attack on the World Trade Center, seems far too new, far too contemporary for archaeological research. And if that weren’t reason enough to steer clear, Gitmo remains firmly out-of-bounds to nearly everyone, a terra incognita behind barbed wire on an American naval base in Cuba.

But none of this stopped archaeologist Adrian Myers, who is currently finishing off his Ph.D at Stanford, from taking a good hard look at Gitmo and drawing up the first independent public maps of the facility. Continue reading

Fleas suck. They also bite. But feeding strategies and a millennia-spanning role in the spread of disease and misery aside, the parasitic insects also happen to be quite remarkable little biomechanical machines. The very definition of minuscule, these wingless wonders can easily jump 100 times their own body length, a skill that scaled to human dimensions would make even Superman seem a little earthbound in the leaping department.

Fleas suck. They also bite. But feeding strategies and a millennia-spanning role in the spread of disease and misery aside, the parasitic insects also happen to be quite remarkable little biomechanical machines. The very definition of minuscule, these wingless wonders can easily jump 100 times their own body length, a skill that scaled to human dimensions would make even Superman seem a little earthbound in the leaping department.

The flea’s secret lies not in extraordinary musculature or the rigorous training that made the old-time flea circus great, but in well-placed deposits of an elastic protein called resilin. (Imagine, roughly, a tightly-wound butt spring that can be tripped at a moment’s notice.) The resulting release of energy accounts for acceleration on the order of 150 g—150 times the force of gravity, or about 30 times the maximum experienced at Whistler’s lethal luge run in the 2010 Olympics.

The resilin spring was discovered decades ago, but it wasn’t until this week that biologists finally described the detailed mechanics of flea leaping in unequivocal terms. It has to do with pushing off from the toe rather than the knee, which might seem just a little inconsequential, the biological equivalent perhaps of the old debating exercise about dancing angels and needle tips. But the philosophers didn’t have high-speed videos of their conundrum. The entomologists do, and they’re just about as delightful as dancing angel toes, after the jump…

The latest alien planets hit the news like fireworks, I write about them a lot, and I’ve always found them boring. I’d been convinced early on by an eminent astronomer who said flatly that finding extra-solar planets wasn’t, as he said, interesting. In the first place, observations were nearly impossible and decades of claims turned out to be mistaken. In the second, stars could have planets, obviously, ours did; exoplanets were neither a surprise nor a clue to how the universe worked. In the mid-1980’s, a dedicated planet hunter told his interviewer he was too embarrassed to admit he looked for exoplanets so he kept it secret and fudged proposals for telescope time by saying he was looking for failed stars. So in the past months, the excitable press releases and news stories about this and that new planet? I say, pish. Turns out I’m wrong.

The latest alien planets hit the news like fireworks, I write about them a lot, and I’ve always found them boring. I’d been convinced early on by an eminent astronomer who said flatly that finding extra-solar planets wasn’t, as he said, interesting. In the first place, observations were nearly impossible and decades of claims turned out to be mistaken. In the second, stars could have planets, obviously, ours did; exoplanets were neither a surprise nor a clue to how the universe worked. In the mid-1980’s, a dedicated planet hunter told his interviewer he was too embarrassed to admit he looked for exoplanets so he kept it secret and fudged proposals for telescope time by saying he was looking for failed stars. So in the past months, the excitable press releases and news stories about this and that new planet? I say, pish. Turns out I’m wrong.

The news comes mostly from one satellite called Kepler, which looked through 156,453 stars and found 1,235 things that looked like planets. If you’re more convinced by large numbers than small — and you should be — and even if most of them turn out not to be planets, then Kepler is pretty convincing. Kepler is interesting too, but less because it’s finding other earths that have life and that we can go and visit: it hasn’t and we can’t. And besides, we already know planets can have life. Kepler’s planets are interesting because they’re some of the first real evidence for how planets form and what solar systems look like.

Before anybody had real data, the leading theory for planet formation hadn’t strayed too far out of the 18th century. And theorists thought solar systems would probably, to first order, look like ours: a nice orderly star orbited at a discrete distance by smallish rocky planets and farther out, by big fluffy planets, all going the same direction and aligned in the same flat plane. These new planetary systems — not all of them via Kepler — look like all hell. Continue reading

For animal lovers, there may be no one more heroic than Dr. Dolittle, the title character of Hugh Lofting’s charming children’s books and Richard Fleischer’s schmaltzy movie (one of my childhood favorites). Dolittle’s patients are people, at first, until they get fed up with his growing number of house pets — rabbits, mice, pigeons, a duck, an owl, and a baby pig, among others. (One lady inadvertently sits on a hedgehog sleeping on the sofa.)

Soon Dolittle has major money troubles, and is squandering his savings on food and care for all those animals. The future is bleak. Then one morning his parrot, Polynesia, teaches him how to speak bird. After some study, he can understand all of the animals. He becomes the best animal doctor in the world, goes on all kinds of fantastical adventures, and shows us the virtue of caring for all forms of life. Animal ailments, we learn, are a whole lot like human ailments.

I thought of the good doctor today after reading about a new conference called Zoobiquity that happened a couple of weeks ago in Los Angeles. More than 200 doctors and veterinarians met to talk about how the same problems — infections, cancers, heart troubles, even mental illness — affect different species. I wish I had been there; get a load of these session titles: Glioblastoma in an Alpaca and a School Principal; Diabetic Syndromes in New and Old World Monkeys; Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in a Polar Bear and a Novelist.

Continue reading

The publisher did what publishers don’t much do these days: send the author on the road. The book tour did what book tours don’t much do these days: sell books. The evening of my return from the book tour, I received a Google Alert that a major newspaper was doing with my book what major newspapers don’t do much these days with any book: reviewing it. That night I went to bed with visions of double-digit Amazon numbers dancing in my head.

The publisher did what publishers don’t much do these days: send the author on the road. The book tour did what book tours don’t much do these days: sell books. The evening of my return from the book tour, I received a Google Alert that a major newspaper was doing with my book what major newspapers don’t do much these days with any book: reviewing it. That night I went to bed with visions of double-digit Amazon numbers dancing in my head.

The next morning, my wife woke me up. Type in your name or the title of your book on Amazon, she whispered, and you don’t get the book.

I love sleep, but I’ve been getting far too little of it. My harried days have been stretching into late nights spent staring at the computer. And I’m not alone. The National Sleep Foundation estimates that the average American gets just 6.7 hours of sleep a night on weekdays.

I love sleep, but I’ve been getting far too little of it. My harried days have been stretching into late nights spent staring at the computer. And I’m not alone. The National Sleep Foundation estimates that the average American gets just 6.7 hours of sleep a night on weekdays.

We’re all familiar with the side effects of sleep deprivation — drowsiness, crankiness, an unnatural fixation with beds and pillows. But did you know that a lack of sleep can cause weight gain?

Anecdotally, this feels true. Late at night you can find me ransacking the cupboards for wayward cookies or stuffing myself with gummy bears. Staying up late makes me want to eat junk. And my unhealthy cravings continue into the next day. Tired and cranky, I make myself bacon or tater tots or peanut butter and Nutella sandwiches (shut up, they’re delicious). Continue reading