“Light thickens, and the crow makes wing to the rooky wood.” MacBeth is talking, telling his wife it’s a good night to murder the king. Even a century earlier, the collective noun was “a murder of crows.” Three centuries later, a poet watches a horse that’s been shot: “gorged crows rise ragged in the wind. The day/ After death I had gone for farewell, and the eyes/ Were already gone – that/ the beneficent work of crows.” A year ago I watched a crow kill and eat a nestling robin. Nobody likes crows. I think it’s because they’re so black – black feathers, black legs, black bills, black eyes. They look like flying shreds of a medieval hell. Continue reading

“Light thickens, and the crow makes wing to the rooky wood.” MacBeth is talking, telling his wife it’s a good night to murder the king. Even a century earlier, the collective noun was “a murder of crows.” Three centuries later, a poet watches a horse that’s been shot: “gorged crows rise ragged in the wind. The day/ After death I had gone for farewell, and the eyes/ Were already gone – that/ the beneficent work of crows.” A year ago I watched a crow kill and eat a nestling robin. Nobody likes crows. I think it’s because they’re so black – black feathers, black legs, black bills, black eyes. They look like flying shreds of a medieval hell. Continue reading

The email was the opposite of scary. Subject: “Your Genetic Profile is Ready at 23andMe!” Six weeks earlier, I had mailed the genetic testing company a tube of my own spit. Now it was time for me to “start exploring” the results. I was terrified.

The email was the opposite of scary. Subject: “Your Genetic Profile is Ready at 23andMe!” Six weeks earlier, I had mailed the genetic testing company a tube of my own spit. Now it was time for me to “start exploring” the results. I was terrified.

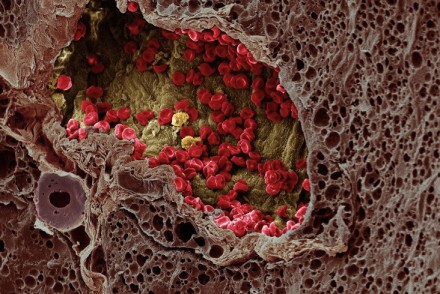

I read a lot about genetics, so I knew that this sort of test isn’t usually very useful, health-wise. 23andMe estimates your risk of getting common diseases — heart disease, diabetes, asthma, and many others — based on large studies of people who carry the same DNA-letter blips as you do. Think of a chromosome as a long string of DNA letters. According to one study, people who have a ‘T’ on one spot of chromosome 8 have a 4-fold higher risk of stomach cancer than do people who carry a ‘C’ on the very same spot. That may sound awful for T people, but in real numbers, it means C people have a really tiny risk, and T people have a slightly-less-tiny, but still tiny risk. In other words, the vast majority of people who carry the “high-risk” T will never get stomach cancer.

I understood all of this and was quite familiar with the oodles of scientific commentaries and popular press articles and books about why these risk tests probably aren’t worth fussing over. Their interpretation is so fuzzy that some doctors think they shouldn’t be sold to consumers without expert supervision. Like a rebellious teenager, I loathe this kind of paternalism, and bought the test partly in defiance. If I waited too long, regulators might deny me the opportunity. I’ll show them!

So after all of that huffing and puffing and spitting and waiting, I finally had access to my precious genetic profile. And I was scared of the damn website.

Continue reading

“The object of war is not to die for your country but to make the other bastard die for his.” – George S. Patton

“The object of war is not to die for your country but to make the other bastard die for his.” – George S. Patton

Early American warfare has always seemed — to me, at least — rather quaint. Men in uniforms line up in a grassy meadow. They march toward one another. They fire, reload, and fire again. Whichever army shoots the most people wins. I never assumed the battles ended with handshakes and backslaps, but they still seemed rather sportsmanlike.

So you can imagine my surprise when I stumbled across a 2004 paper in the Colonial Williamsburg journal titled “Colonial Germ Warfare.” Germ warfare? In the 1700s?

As a matter of fact, yes. It turns out biological weapons have a long and sordid history dating back to way before colonists were killing redcoats (or vice versa). I learned that Hannibal, the Carthaginian commander best known for leading an army over the Alps atop an elephant in 218 B.C., used to catapult pots filled with snakes toward enemy ships. A little more digging led me to a paper enticingly titled, “The History of Biological Warfare,” which contains gems like this:

In 1495, Spanish forces supplied their French adversaries with wine contaminated with the blood of leprosy patients during battles in Southern Italy. In the seventeenth century, Polish troops tried to fire saliva from rabid dogs towards their enemies. Continue reading

(This post is the third in a three-part series. The first and second appeared the past two Fridays.)

“What can we as scientists do to better communicate science to the general public?”

“What can we as scientists do to better communicate science to the general public?”

This question didn’t stump me, but, I admit, the answer did elude me at first. I started talking about how writers are dependent on the good will of scientists in communicating what they do to the general public. I said that scientists should be eager to talk with us—which, in my experience, they already are. I said they should see it as almost a civic responsibility—which, in my experience, they already do. And I said that writers should be careful about how accurately they portray the nuances of science—which, in my experience, they sometimes aren’t. But from the looks on some of the faces in the auditorium, I didn’t seem to be adding much to the conversation, if only because I was talking about the writer’s role in better communicating science to the general public. The question, however, was what can scientists do. The scientists in this room wanted to know—really, really wanted to know.

In the year 111 BCE, the emperor of China sent his emissaries westward to the land of the Wusun. The emperor had grown tired of the Central Asian nomads who routinely swept into his villages, stealing the grain, making off with the women and burning the houses. Wudi realized he needed better, faster horses to drive them out, so he sent his envoys far west to the Wusun. A people of the steppe, the Wusun reportedly possessed a horse of exceptional beauty, speed and endurance. Indeed, this horse was said to have descended from the heavens. When it galloped, it sweat blood.

In the year 111 BCE, the emperor of China sent his emissaries westward to the land of the Wusun. The emperor had grown tired of the Central Asian nomads who routinely swept into his villages, stealing the grain, making off with the women and burning the houses. Wudi realized he needed better, faster horses to drive them out, so he sent his envoys far west to the Wusun. A people of the steppe, the Wusun reportedly possessed a horse of exceptional beauty, speed and endurance. Indeed, this horse was said to have descended from the heavens. When it galloped, it sweat blood.

Wudi traded an imperial princess for several of these horses, only to discover that he had been swindled. The animals belonged to inferior breeds. But the emperor refused to give up. He sent an entire army in 103 BCE to what is now eastern Uzbekistan to find and capture some of the horses. His imperial forces suffered terrible losses and deprivation, but they succeeded in finding nearly two dozen superior horses, which they transported back to the imperial stables. There the Chinese court called them tianma, “heavenly horse.” The breed became the favorite mount of Chinese emperors and nobles.

I was reminded of this imperial obsession last week by news out of Xi’an, one of China’s ancient capitals. While excavating the massive mausoleum of Emperor Wudi, Chinese archaeologists found skeletal remains of 80 horses that had been sacrificed and buried in two cavernlike pits. At the entrance to each cavern lay the skeleton of a stallion as well as a small terracotta warrior. Continue reading

A few years back, when anyone Googled me, they were directed to a bunch of (and I apologize but there is just no nice way to say this, though those nice British editors at New Scientist tried) piss fetish sites. This had nothing to do with my predilections, which I must hasten to add don’t venture in that direction. So how did this happen? Crowd in, boys and girls: this turns out to be a story about search engine optimization.

Back in 2003, I engaged in an all-too-detailed email correspondence about the office “seat sprinkler” and the increasingly desperate attempts of a counter-sprinkling vigilante. (N.B.: ladies room vigilantism = rhyming “sweetie” with “seatie.”) My partner in the email exchange thought it was funny enough to forward to a friend who ran an irreverent web site. This was years before anyone was writing jeremiads about the longevity of information on the Internet.

Four years later, I finally reaped the whirlwind of an internet presence left too long to its own devices. Long after the lights had gone dark at the place that hosted the original content, the email exchange lived on, in a wholly different context.

But the question that baffled me was this: why was this long-dead content all over the first page of my Google results? How did it even get onto a single fetish site, never mind multiples? And really, Google had no interest in my citations on academic papers or in those college theater productions? Those fetish sites were seriously the most compelling way I could be represented on the entire internet?

I asked a search engine optimization expert to help me find answers. Judith Lewis, head of search at Beyond, a brand reputation tracking firm based in London, reconstructed the chain of events for me. After the original content hit the internet, Google immediately stowed it in its cache, just as it does all content–caching is the reason everything you put on the internet lives forever. After the original web site went offline when its owners lost interest, Google’s cache still contained the full story.

Next came aggregator web sites, which crib content they deem relevant based on select keywords. These sites send out software known as crawlers (programs that look for mentions of the select keywords) to retrieve any content that fits the bill and basically paste it onto their site. There are many aggregator sites, the most high-profile of which gather marketing data based on your shopping habits. They also trawl the Google cache, which is where Lewis suspects they found my email exchanges. Then several other fetish sites re-plagiarized the original enterprising fetish site. With enough of those fetish sites linking to each other, Google became convinced that these sites were important–certainly more important than the worthy little academic paper. (SEO types refer to these kinds of linking strategies as “Google juice.”) That’s how these sites became the most relevant search results for my name.

That’s how reputation works online. It’s all about the most powerful sites that carry your name. And power = links.

Captain Matty is a brilliant storyteller. I know because earlier this month I went on his famous tour through the rainforest of Far North Queensland, Australia. As he drove our orange bus up petrifyingly narrow, sinuous roads, Matty told tales, tall and short: about the legendary ‘drop down‘, wicked cousin of the koala, so named because it crashes down from the treetops onto its prey (including, Matty said with a wink, a Swiss-German tourist); about attending poisonous snake bites (it involves a credit card and lots of gauze); and about Aboriginal women who use a sacred waterfall to boost fertility. His most remarkable story was about the rainforest.

The Wet Tropics of Queensland span some 280 miles of coastline on the northeast side of the country, running parallel to the Great Barrier Reef. Thanks to the mash-up of Australian and Asian continental plates 15 million years ago, the area holds a supremely diverse mix of animals and plants (some of which are as much as 415 million years old). It’s difficult to describe without getting carried away, but I’ll try.

The region’s 3,000 plant species include 13 types of rainforest, as well as woody bush, mangroves and swampland. Now fauna: 370 species of birds, 58 frogs, 41 marsupials, 36 bats. Twelve of its mammals — including green ringtail possums, a masked white-tailed rat, and two tree kangaroos — exist nowhere else in the world.

The region’s 3,000 plant species include 13 types of rainforest, as well as woody bush, mangroves and swampland. Now fauna: 370 species of birds, 58 frogs, 41 marsupials, 36 bats. Twelve of its mammals — including green ringtail possums, a masked white-tailed rat, and two tree kangaroos — exist nowhere else in the world.

Continue reading

“What can we do about high school physics textbooks?”

The question, I admit, stumped me. Not in the way that a question about whether gravity exists in other universes would stump me. That question I wouldn’t be able to answer because there isn’t an answer; the existence of other universes is speculative. This question, however, I couldn’t answer simply because I didn’t know that there was anything to be done about physics textbooks. I admitted my ignorance, said I would have to educate myself, and called on another raised hand.

Still, I couldn’t stop thinking about the question. It came during a Q&A session after a talk I gave last month at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. I had just spent 45 minutes explaining to an auditorium full of about 150 physicists the methodologies I use in trying to make science accessible to non-specialist readers, and I had been reading passages from my new book to illustrate my points. That whole discussion, I now realized, was predicated on the assumption that readers come to astronomy or cosmology knowing basically nothing about the physics of the universe, much like I do before I start my research. This ignorance isn’t exactly a given; questions about Newtonian dynamics or antimatter occasionally arose during my book tour. But if my overall experience was any indication, ignorance is a safe bet. Continue reading