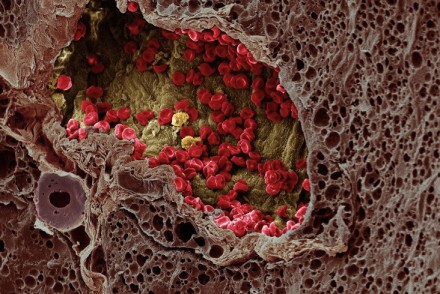

Baltimore has a hard-core drug problem. The evidence is unmistakable. Head down an alley in the wrong part of town and you’re liable to find a discarded needle, some broken vials, and maybe even a shell casing or two. Why, yes. That was a gunshot. See that guy on the corner? No, he’s not tired. He’s high. Really, really high.

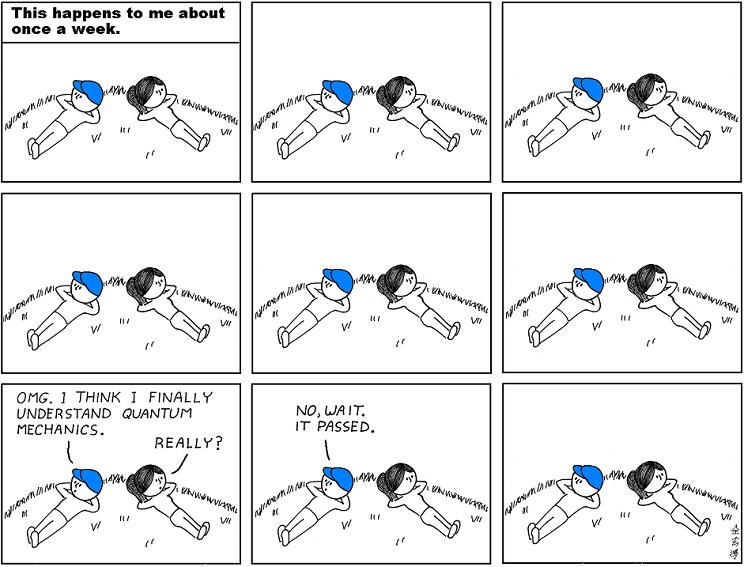

My fascination with Baltimore’s heroin addiction began in 2006. I can’t say what drew me to the seedy side of the city, but I quickly became obsessed. I took photograph after photograph of shuttered row houses. I donned a bulletproof vest and cruised West Baltimore with the cops. I sat in the needle exchange van and handed out clean syringes. I watched The Wire. I dropped the F-bomb with alarming frequency. I used pushpins to painstakingly mark the location of every murder on a map taped to my dining room wall. Truth be told, I went a little nuts. I thought getting close to the drug problem might help me make sense of it.

David Epstein at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) has come up with a far better way of understanding the epidemic. Continue reading

The email was the opposite of scary. Subject: “Your Genetic Profile is Ready at 23andMe!” Six weeks earlier, I had mailed the genetic testing

The email was the opposite of scary. Subject: “Your Genetic Profile is Ready at 23andMe!” Six weeks earlier, I had mailed the genetic testing