When you hear that someone has had a stroke, what type of patient are you likely to picture? Probably an elderly person with an illness, such as heart disease.

But the patient might be a lot younger than you’d think: after the elderly, babies around the time of their birth are next most likely to suffer a stroke – a disruption in blood flow to the brain that kills cells by starving them of oxygen. Most babies who survive a stroke develop lifelong problems with speech, hearing, learning, and movement; stroke is the leading cause of the incurable movement disorder cerebral palsy.

Yet despite the emotional and financial cost of caring for these children, few researchers are looking for treatments for them. That’s perplexing in light of the past decade’s revolution in neuroscience: researchers have realized that the brain, once thought incapable of repairing itself, can grow new brain cells, or neurons. They’re investigating how to harness that ability to treat conditions that afflict adults, such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease. But few researchers are studying how this astonishing flexibility could be enlisted to help children with brain diseases.

That’s partly because neuroscience research on babies and children is difficult – with good reason. Kids can’t give their own consent to be test subjects; their parents are reluctant to let doctors do anything that might harm their children, or add time and stress to their lives; and it’s hard to study babies’ brains in any meaningful way. One of the major ways that scientists study the brain is by collecting samples from deceased patients, but parents who have lost their children are often understandably too distraught to agree to donate their baby’s tissue to a brain bank.

David Rowitch, a neuroscientist at the University of California San Francisco, is trying to change this. Rowitch is not only a neuroscientist; he’s also a pediatrician who specializes in treating the most fragile infants. In 2008, Rowitch and other doctors at UCSF opened one of the world’s only infant intensive care nurseries focused on preventing and treating newborn brain injuries. He has also developed a pediatric brain bank – a collection of brain tissue from 100 deceased babies and children, some of whom died before birth.

The brain bank is small, but uniquely designed to explore the development and ailments of the youngest brains. Its tissues are collected soon after death and are better preserved than brain tissue in other pediatric brain banks. The tissue includes regions where neurons are born before they migrate elsewhere in the brain. Tissue banking is controversial and unethical when tissue donors don’t realize that their cells are being studied in research. But Rowitch’s team always explains to families what this brain bank is for and how it will be used. And while it is heartbreaking to think of babies dying, and may seem macabre to collect tissue from them, it’s essential if researchers want to find treatments for the ailments that have claimed their lives.

Rowitch has just showed this in a paper published in Nature Neuroscience. Drawing on the brain bank, he and his colleagues examined samples of brain tissue from babies who died after suffering brain injuries due to lack of oxygen. He found that patches of damaged tissue in their brains expressed a certain gene found in cells that make a protective substance called myelin. But the cells weren’t making myelin, and the brain tissue surrounding them had died. Rowitch thought he knew why: the gene affected in the myelin-making cells is part of a molecular developmental pathway – the so-called Wnt (pronounced “wint”) pathway – that seemed to be stuck.

Rowitch wondered what would happen if he coaxed this Wnt developmental pathway to restart itself. So he treated mice with similarly damaged brain cells with a drug designed to do that. The brain cells started making myelin again, effectively repairing the damage.

Rowitch needs to do a lot more work to show whether drugs could help human babies – not just mice – with brain injury. But the paper is a hopeful demonstration that baby brain injuries might one day be repaired. And it’s part of a growing movement among pediatricians and neuroscientists to look again at childhood conditions such as cerebral palsy that are caused by brain damage. Maybe they aren’t untreatable, as has been thought for so long.

The brain regeneration revolution is finally trickling down to the littlest among us. It’s about time.

***

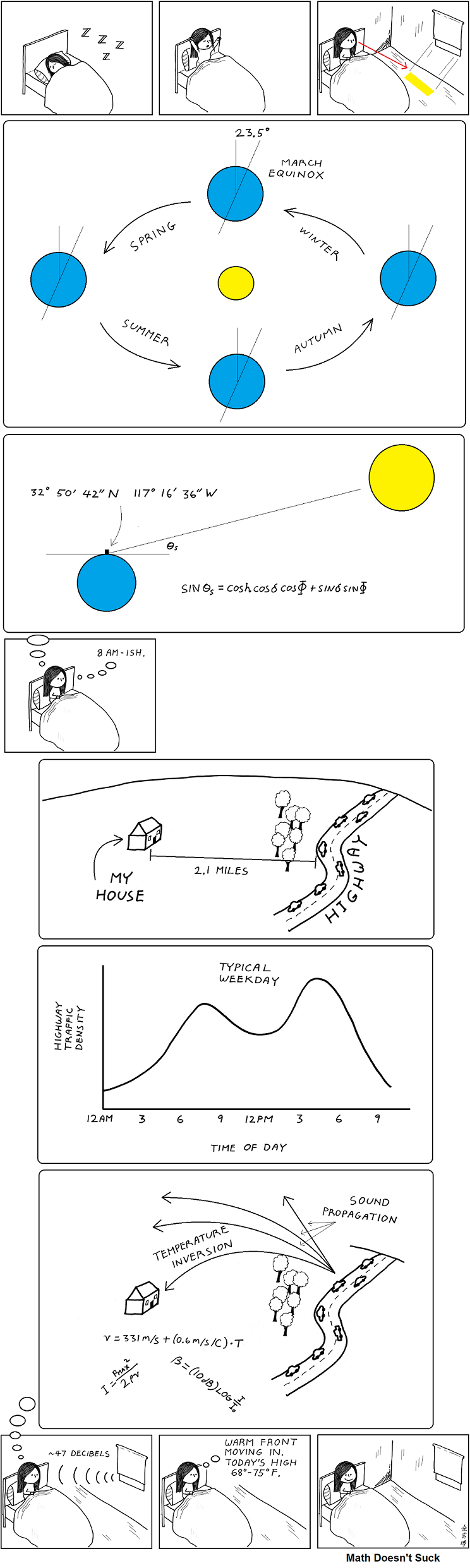

Image: A newborn takes her hearing test. kandinski/flickr.

My friend Taya and I were out at her parents’ country place, about twelve acres in the western foothills of the Cascades. I was maybe eight, visiting for the first time. Taya was taking me on a tour. We were struggling along, as short-legged people do through dense, early successional Northwest forest. She stopped and took hold of a small sapling. “This,” she said, “is the difference between our land and a park.” And then, shockingly, she stepped on the sapling until it was bowed in two and then snapped it with her boot, killing it dead. Or maybe she ripped it out of the ground with her two hands—she was a very strong girl, I remember. I don’t remember the details of the act. But I do remember that she killed a tree and also the sensation of my mind being blown right out my ears. (Taya’s childhood arbor-cide didn’t presage sociopathy or anything close to it. She’s now a vet.)

My friend Taya and I were out at her parents’ country place, about twelve acres in the western foothills of the Cascades. I was maybe eight, visiting for the first time. Taya was taking me on a tour. We were struggling along, as short-legged people do through dense, early successional Northwest forest. She stopped and took hold of a small sapling. “This,” she said, “is the difference between our land and a park.” And then, shockingly, she stepped on the sapling until it was bowed in two and then snapped it with her boot, killing it dead. Or maybe she ripped it out of the ground with her two hands—she was a very strong girl, I remember. I don’t remember the details of the act. But I do remember that she killed a tree and also the sensation of my mind being blown right out my ears. (Taya’s childhood arbor-cide didn’t presage sociopathy or anything close to it. She’s now a vet.)