My mother was an old lady, she’d lived a good and useful life, and she died a year and ten days ago. I hadn’t been keeping track of her death’s anniversary but I didn’t need to; I only had to figure out why I was walking around feeling, for no good reason, sad. One of my cousins wrote to me, “I’m sorry you are sad, Annie. Thursday my new couch was delivered. I cried as my old one left – apparently I had an undiscovered attachment to it.” My cousin recently moved to a new house with a new love; the old couch was from her old life, years ago, when her husband had died. Sad in early August? Crying over couches? Really? Science, as it often does, has a nice metaphor: resonance. Continue reading

My mother was an old lady, she’d lived a good and useful life, and she died a year and ten days ago. I hadn’t been keeping track of her death’s anniversary but I didn’t need to; I only had to figure out why I was walking around feeling, for no good reason, sad. One of my cousins wrote to me, “I’m sorry you are sad, Annie. Thursday my new couch was delivered. I cried as my old one left – apparently I had an undiscovered attachment to it.” My cousin recently moved to a new house with a new love; the old couch was from her old life, years ago, when her husband had died. Sad in early August? Crying over couches? Really? Science, as it often does, has a nice metaphor: resonance. Continue reading

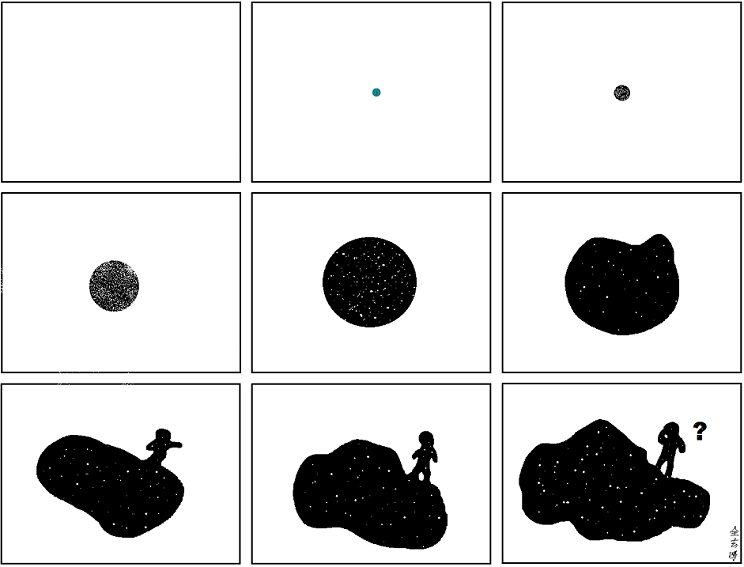

AG’s sneaky caption this time is “. . . we are the universe made manifest, trying to figure itself out. — Delenn or Carl Sagan.” It’s apparently a quote from Delenn who is apparently some scifi character who says portentous things. Carl Sagan was real; also said portentous things; and undoubtedly said something like that, probably in a book called The Pale Blue Dot when he talked about the anthropic principle.

I’m fond of the anthropic principle because I published my first feature on it. But it’s an Alice-in-Wonderland rabbit hole of an idea. In its simplest form, it says that of all the possible ways the universe could have evolved, it must have taken the path that ended in us. As astrophysicist, David Hogg, says, “No duh.” Theorists use it to understand how the universe began: the infant universe couldn’t have had, say, a gravitational force so small that we now wouldn’t stick to the earth.

Its more complex forms — even the ones that are more scientific than philosophical, let alone religious — just make my head hurt. I’m steadfastly avoiding the the websites of the Wonderland. I’m not even going to link to them. You can google them if you like, but I don’t recommend it. Ok, if you really have to, then here. But don’t come complaining to me afterward.

Among my fondest childhood memories are the hours my family spent discussing B cells and T cells while cruising the highways on our family car camping trips.

Among my fondest childhood memories are the hours my family spent discussing B cells and T cells while cruising the highways on our family car camping trips.

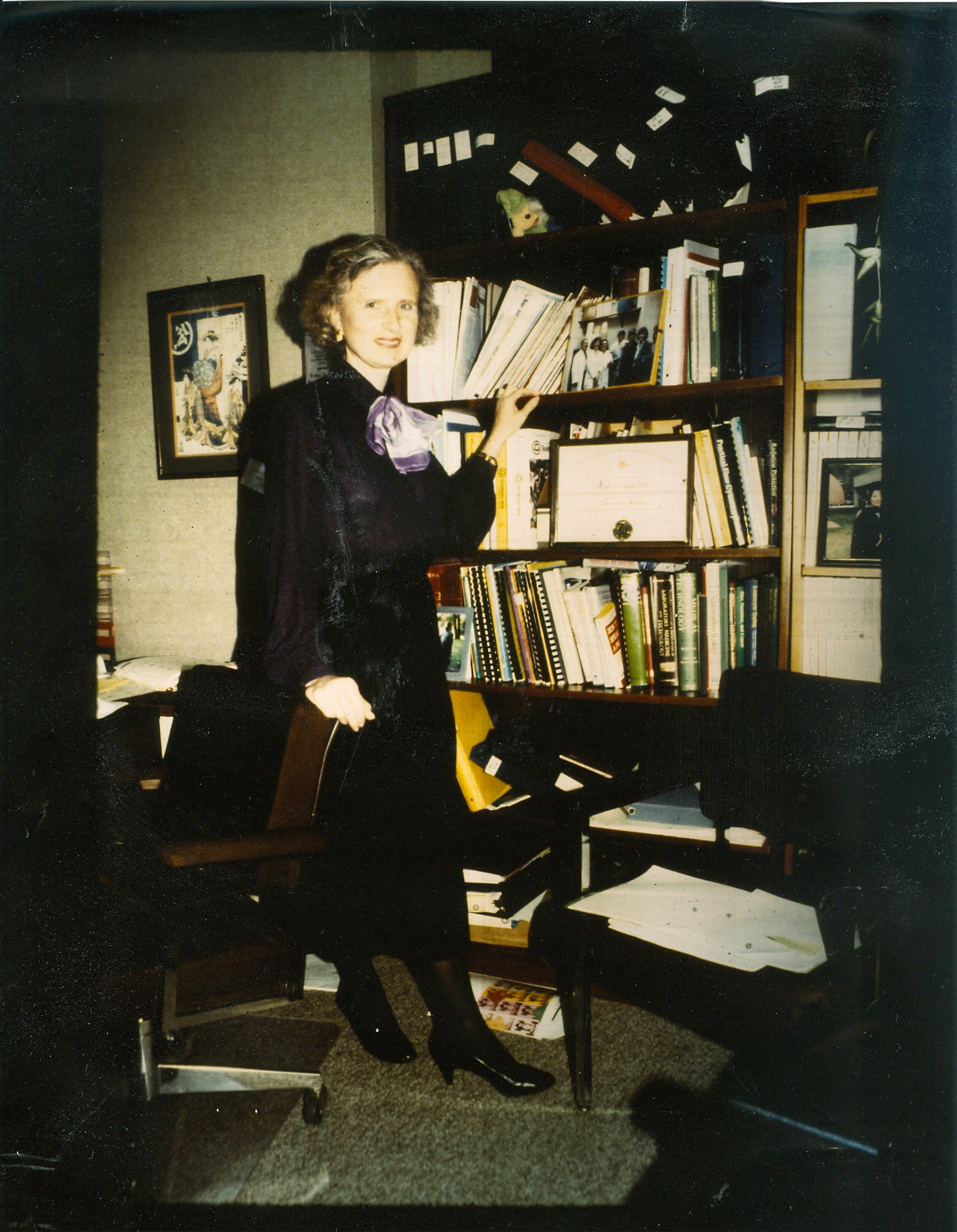

My mother, Irene Check, is a scientist; both she and my father got their doctoral degrees in microbiology, and my mother has a specialty in immunology – the study of the body’s defense against disease. What I remember most from our childhood conversations is my mom’s excitement about science: B and T cells are the main types of cells that do the work in the human immune system, but when my mom talked about them, they sounded like more than mere cells; they sounded like superheroes.

These days, however, my mom is a lot more than a scientist: she works on the front lines of health care reform. My mom directs an immunology laboratory in a hospital, which means that she runs tests to try to diagnose what’s wrong with patients’ immune systems. And while her love of science is what got her there, she now spends as much of her time cutting costs and trying to prepare for health care reform as she does using her scientific knowledge to help sick people.

Last week my little black dog wandered off into the sloping hillside behind our Colorado home. Fifteen years old, deaf and suffering from congestive heart failure, she appeared to have succumbed to some primordial call to return to the wilderness to die.

Last week my little black dog wandered off into the sloping hillside behind our Colorado home. Fifteen years old, deaf and suffering from congestive heart failure, she appeared to have succumbed to some primordial call to return to the wilderness to die.

She didn’t have far to go. My husband and I live in the foothills of the Rockies, at the quintessential intersection of wildland and suburban living. Houses and ponderosa pines alternately dot the rolling lots; ravines provide the perfect corridors for critters to journey down from higher elevations.

When we bought the house last year, one of the first discoveries we made on poking through local maps was that we were smack-dab in the middle of the local “summer bear concentration.” Next we read David Baron’s chilling The Beast in the Garden, about a mountain lion that in 1991 had killed and eaten an 18-year-old male athlete who was out jogging after a pepperoni pizza lunch. Within view of an interstate highway. Not too many miles from our new house.

Yet over time, we never saw a bear other than its scat or the occasional fur tuft on the barbed-wire fence. Cougars made not a single appearance. One may have made it from the Black Hills to Connecticut recently, but none have figured out how to parse the few miles from the high country to our back yard — at least while we were watching.

What we do, have, though, are foxes. Continue reading

Last month, I recommended a few children’s books that I thought reflected the curious, adventurous, and humble scientific spirit of The Last Word on Nothing. Friends and readers have since added their favorite titles to the list — thank you! May these books bring all of you, and the young explorers in your lives, some late-summer reading pleasure.

Last month, I recommended a few children’s books that I thought reflected the curious, adventurous, and humble scientific spirit of The Last Word on Nothing. Friends and readers have since added their favorite titles to the list — thank you! May these books bring all of you, and the young explorers in your lives, some late-summer reading pleasure.

A Log’s Life by Wendy Pfeffer, recommended by science journalist Jill Adams.

Bats at the Beach by Brian Lies, recommended by Colorado horsewoman and bon vivant Marla Bear Bishop.

The Magic School Bus series, recommended by science journalist Siri Carpenter and by Kim Todd (author of the terrific grownup science books Chrysalis and Tinkering with Eden).

I don’t have a problem with screenwriters fudging scientific truths as long as they: are internally consistent with their made-up science; and manipulate the facts in the name of telling a good story.

I don’t have a problem with screenwriters fudging scientific truths as long as they: are internally consistent with their made-up science; and manipulate the facts in the name of telling a good story.

Rise of the Planet of the Apes, which came out on Friday, follows the first rule and tries to follow the second (more on that later), so I’m not upset that it gets a few things wrong about gene therapy. Still, I feel it’s my duty to tell you what was not quite right, and describe a few real advances in the field.

Continue reading

As an undergraduate biology student, I loathed taxonomy. Plant systematics was the only college course I remember absolutely hating. It seemed like nothing more than rote memorization. I studied with flash cards I’d made on little index cards. Bracts instead of sepals, colored glands that take the place of petals? Probably a Euphorbiaceae.

I spent hours memorizing distinctions like these, and I considered this kind of knowledge esoteric and pointless. Why did I need to memorize the latin names of a bunch of plants when I could always look them up? Classifying things seemed archaic. I wanted to ponder biology’s bigger questions.

So I’m surprised to find myself making so much practical use of the lessons I learned in that boring class. Continue reading

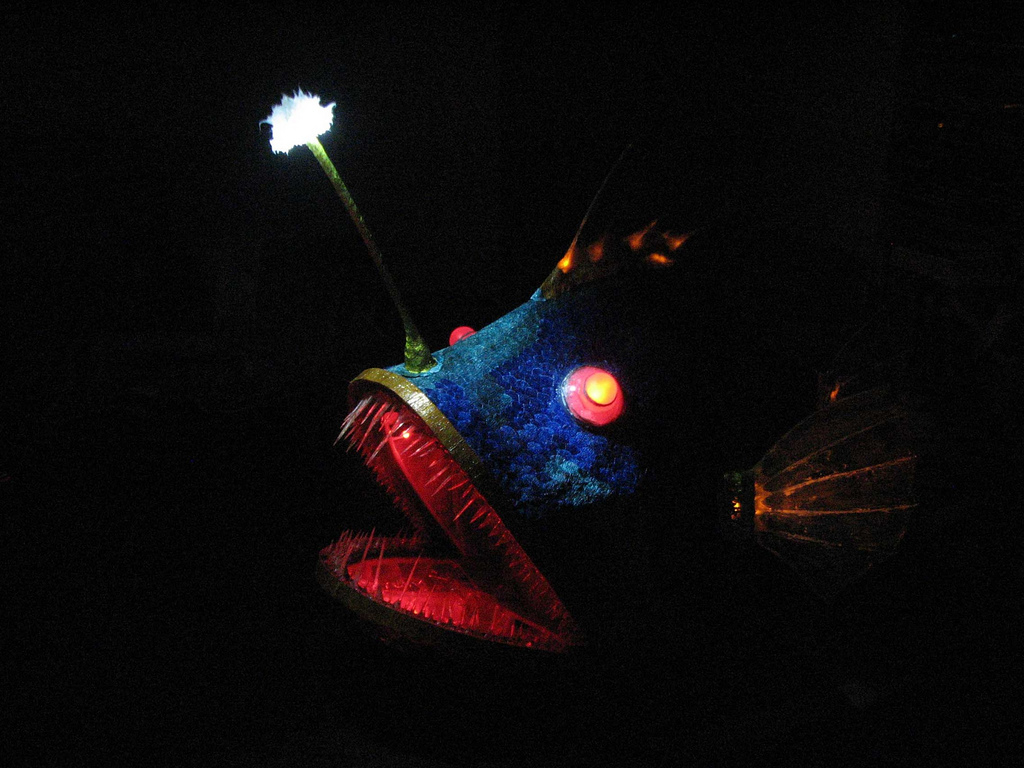

The anglerfish was the iconic animal of my childhood. This eerie creature lives miles under the ocean’s surface and – as you probably know, if you were ever an animal-obsessed kid like me – dangles a fleshy, glow-in-the dark “bait” in front of its monstrous jaws. The dangling bait attracts prey and gives the animal its name. I remember returning to one book illustration of the fish with its jaws agape to reveal deadly sharp teeth over and over again. The anglerfish somehow captured everything mysterious, fascinating, and awesome about the natural world for me.

The anglerfish was the iconic animal of my childhood. This eerie creature lives miles under the ocean’s surface and – as you probably know, if you were ever an animal-obsessed kid like me – dangles a fleshy, glow-in-the dark “bait” in front of its monstrous jaws. The dangling bait attracts prey and gives the animal its name. I remember returning to one book illustration of the fish with its jaws agape to reveal deadly sharp teeth over and over again. The anglerfish somehow captured everything mysterious, fascinating, and awesome about the natural world for me.

I hadn’t thought about the anglerfish until very recently, when I had a child of my own and became re-acquainted with the animals of childhood. It’s shocking how much of kids’ literature focuses on animals that are actually quite remote to our lives. Lions, bears, elephants and giraffes feature prominently, as do monkeys, sharks, whales and other exotic animals. Admittedly, these animals are rad, and totally deserve the attention. But most of us will never see them, except possibly in zoos. Sadly, I have never seen a real live anglerfish – not even in an aquarium.