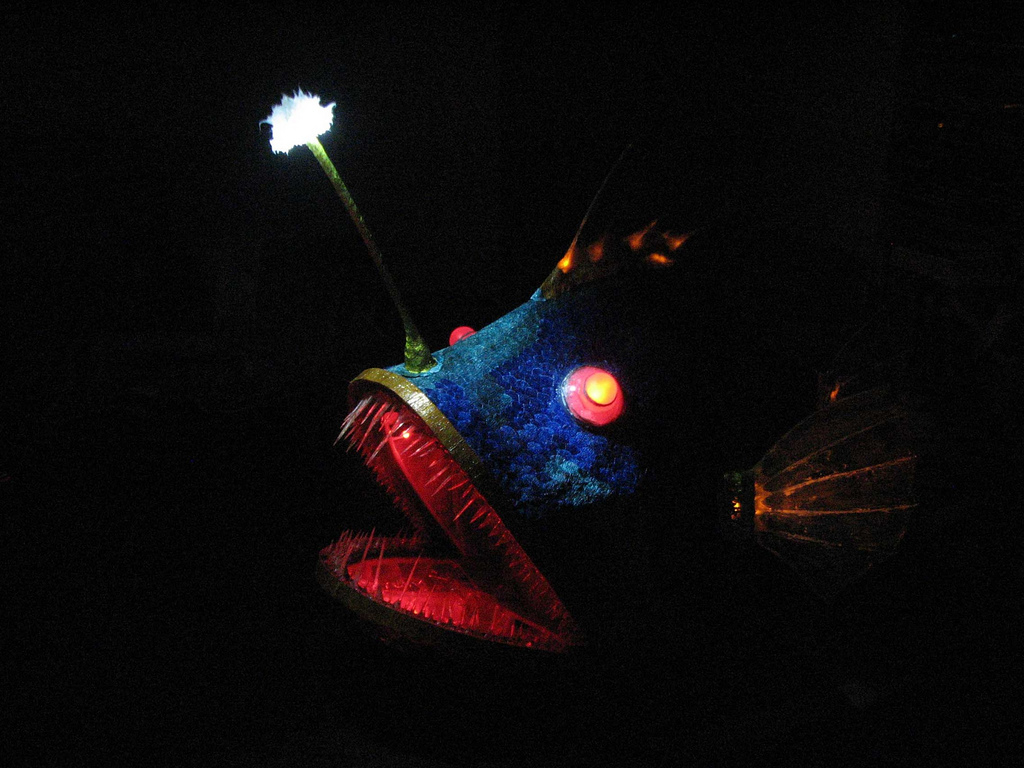

The anglerfish was the iconic animal of my childhood. This eerie creature lives miles under the ocean’s surface and – as you probably know, if you were ever an animal-obsessed kid like me – dangles a fleshy, glow-in-the dark “bait” in front of its monstrous jaws. The dangling bait attracts prey and gives the animal its name. I remember returning to one book illustration of the fish with its jaws agape to reveal deadly sharp teeth over and over again. The anglerfish somehow captured everything mysterious, fascinating, and awesome about the natural world for me.

The anglerfish was the iconic animal of my childhood. This eerie creature lives miles under the ocean’s surface and – as you probably know, if you were ever an animal-obsessed kid like me – dangles a fleshy, glow-in-the dark “bait” in front of its monstrous jaws. The dangling bait attracts prey and gives the animal its name. I remember returning to one book illustration of the fish with its jaws agape to reveal deadly sharp teeth over and over again. The anglerfish somehow captured everything mysterious, fascinating, and awesome about the natural world for me.

I hadn’t thought about the anglerfish until very recently, when I had a child of my own and became re-acquainted with the animals of childhood. It’s shocking how much of kids’ literature focuses on animals that are actually quite remote to our lives. Lions, bears, elephants and giraffes feature prominently, as do monkeys, sharks, whales and other exotic animals. Admittedly, these animals are rad, and totally deserve the attention. But most of us will never see them, except possibly in zoos. Sadly, I have never seen a real live anglerfish – not even in an aquarium.