I’d just sat down when the first carver approached me. It was my second evening in Iqaluit on southern Baffin Island, 2000 kilometers north of Ottawa, and all around me well-heeled bureaucrats were tucking into Arctic char and steak. But the carver, a small weathered-looking Inuk, skirted them and made a beeline toward me. In his calloused hands, he held out a small sculpture for sale. It was a bear–a polar bear carved exquisitely from hard green serpentinite. With its long neck stretched and its head lifted, the carved bear tasted the air. Its maker, Jutai Noah, knew his subject intimately.

I’d just sat down when the first carver approached me. It was my second evening in Iqaluit on southern Baffin Island, 2000 kilometers north of Ottawa, and all around me well-heeled bureaucrats were tucking into Arctic char and steak. But the carver, a small weathered-looking Inuk, skirted them and made a beeline toward me. In his calloused hands, he held out a small sculpture for sale. It was a bear–a polar bear carved exquisitely from hard green serpentinite. With its long neck stretched and its head lifted, the carved bear tasted the air. Its maker, Jutai Noah, knew his subject intimately.

As it happened, I had just come back from a nine-day stay in a remote field camp on southern Baffin Island, and I’d just heard a lot about polar bears. Baffin forms a large part of the Canadian Arctic territory of Nunavut, and Nunavut is home, I’m told, to the largest population of polar bears in the world, as many as 15,000 of these large carnivores. But opinions vary wildly on how these legendary bears are doing in Nunavut these days. Continue reading

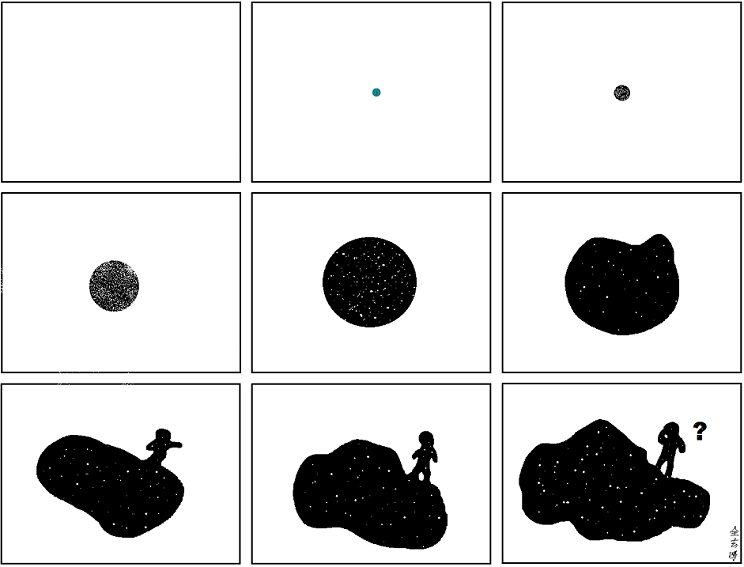

I don’t have a problem with screenwriters fudging scientific truths as long as they: are internally consistent with their made-up science; and manipulate the facts in the name of telling a good story.

I don’t have a problem with screenwriters fudging scientific truths as long as they: are internally consistent with their made-up science; and manipulate the facts in the name of telling a good story.