In our centuries-old tradition of interviewing the Persons of LWON who are authors of newly-published books, here is our interview with Jessa about her new book, The Siesta and the Midnight Sun.

In our centuries-old tradition of interviewing the Persons of LWON who are authors of newly-published books, here is our interview with Jessa about her new book, The Siesta and the Midnight Sun.

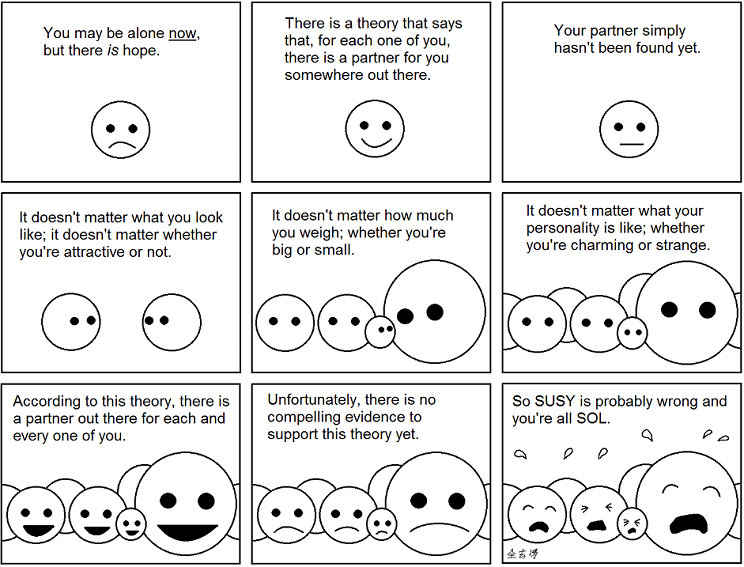

Q: Your book is about, as you say, “the body clock as a biological universal, a foundation on which cultures lay their own rituals and rhythms.” So every living thing has a clock and in each one of those living things, each organ also has a clock? Does the body then have some sort of master clock? I mean, otherwise how does anything get done?

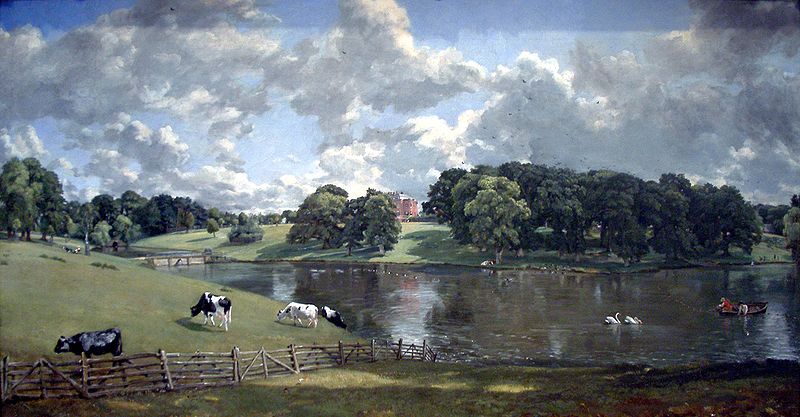

A: Circadian rhythms – or biological clocks that run on daily cycles – are a result of life having evolved on a rotating planet. The human body has lots of internal clocks, oscillations that take roughly 24 hours to complete their cycle, and they are all coordinated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), a bundle of neurons in the brain’s hypothalamus. It conducts the body’s internal orchestra in a few different ways, including triggering melatonin release into the bloodstream to initiate sleep.

Q: How many kinds of clocks are there? or rather, how many kinds of things set the clocks?

A: Sunlight is by far the most important calibration tool the body has for setting its clock. Particularly the blue region of the visible spectrum. You might be familiar with rods and cones — the photoreceptors in the eye – and it turns out there’s a third photoreceptor whose only job is to measure light levels and send that message to the master clock. We’re also capable of setting our rhythms based on social cues, activity rhythms and so on, but those are very weak cues compared with light.

Q: A third photoreceptor! That we don’t use to see! We detect light but don’t see anything! Whoa, calm down. Continue reading →