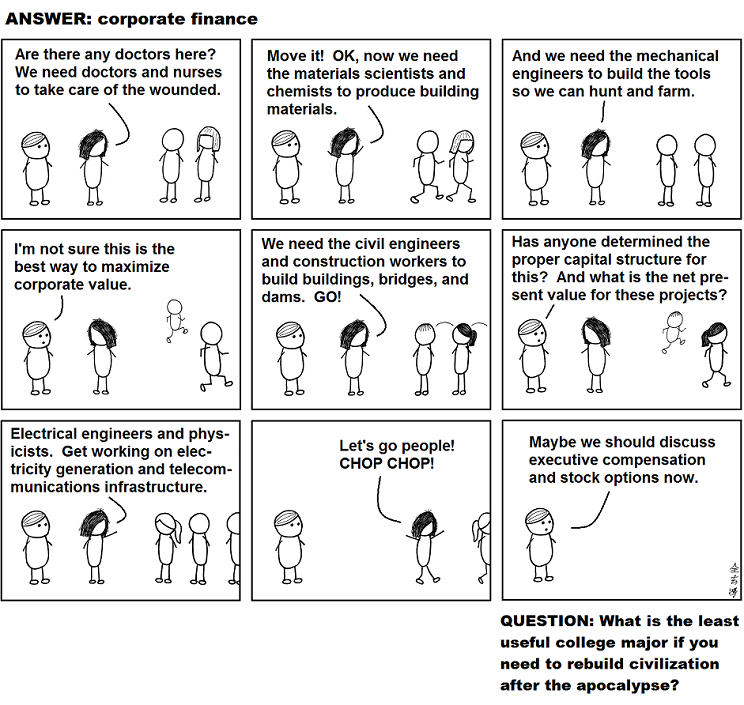

This needs no explaining. I’m about to march on Wall Street myself.

This needs no explaining. I’m about to march on Wall Street myself.

When I’m thrashing through the brambles of a first draft, no story in sight, I have one reliable lifeline. WWJMD? What would John McPhee do to get himself out of this #%&! mess?

When I’m thrashing through the brambles of a first draft, no story in sight, I have one reliable lifeline. WWJMD? What would John McPhee do to get himself out of this #%&! mess?

This, after all, is the guy who found fascinating stories in citrus cultivation. And geology. And Switzerland! Some of his writing is now two generations old, and not, shall we say, of smartphone-friendly lengths. But his work holds up. He knows what readers don’t know they want to know, and he knows how to tell them about it. Those gifts don’t expire.

There are a lot of answers to WWJMD, and a lot of places to find them. You can read his books and pore over The New Yorker archives. You can get hold of the charming and instructive Paris Review interview by his former Princeton student, MacArthur-award-winning journalist Peter Hessler. Or, best of all, you can hear from the man himself.

“Math and graphs are necessary to make a story like this interesting.”

“He doesn’t provide any drawings or graphs, which would have appealed to and been understood by many readers.”

“He tries to describe graphs without using any pictures at all … why? I myself would also have liked some representation of the mathematics, because I believe that many of those interested in this kind of topic has had at least some math & science education, and the others can ignore them.”

Many has, I’m sure. But despite what these online comments about my most recent book contend, the crucial question for someone writing about science for a non-specialist audience is: Will “the others”—readers without the benefit of a math or science education—actually ignore the graphs and charts and equations, or will they, fanning pages in the New Nonfiction aisle or idly clicking “Look Inside!” online, find themselves confronting their inner eighth grader’s greatest nightmare, and go buy The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Subject-Verb Agreement instead?

Last Sunday, the day before the world’s population hit 7 billion, I went to a scientific meeting on the future of contraception.

Last Sunday, the day before the world’s population hit 7 billion, I went to a scientific meeting on the future of contraception.

I had expected to hear, and did hear, about a slew of labs trying to develop a birth control pill for men. What I did not expect: one pill was shown to work in men more than 50 years ago.

In the late 1950s, researchers from the University of Oregon and University of Washington tested drugs called ‘bis(dichloroacetyl) diamines’ on inmates from the Oregon State Penitentiary.* The scientists doled out one of three pills — dubbed Win 13,099, Win 17,416 and Win 18,446 — to 26 volunteers once or twice a day for up to 54 weeks, and measured the men’s sperm counts along the way.

The results were stunning: the compounds reduced the amount of sperm in the men’s semen, and sometimes completely wiped it out. The pills didn’t affect libido, and the only reported side effect was bloating and gas. What’s more, within a few weeks of stopping treatment, sperm counts went back up. It was, perhaps, the horny grail: reversible birth control for men, no rubber required.

Continue reading

As a journalist, I tend to be wary of people trying to assign me stories if they’re not an editor, and sometimes even then. Public relations types try to do it all the time. They send press releases with pre-packaged quotations for the deadline-driven writer or call up with some brilliant story idea that never really smells like news. So when Gregory A. Prince – the CEO of a company that specializes in combating pediatric viral diseases – approached me at a conference and told me he had the perfect story for me, I was prepared for a tone-deaf corporate pitch.

What I got instead was impassioned advocacy for his favourite rodent. Or at least for its use in pharmaceutical research.

The hispid cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus) is a cute little shrew-like thing that makes its nest out of cotton and has a rich brown coat of fur. It looks nothing like a lab rat, but has unique advantages over those ubiquitous albino strains of Rattus norvegicus, in that it models certain human diseases far more faithfully. That is to say, cotton rats can catch infectious diseases – especially respiratory viruses – other rodents can’t. For example, they’re the only rodents whose lung tissue after nasal injection replicates the measles virus, still the most lethal infectious disease of infants in the world. This discovery allows researchers an intermediate, less ethically troubling model between their tissue cultures and their primate measles subjects, macaques.

Though it was the first model animal used in polio research, the cotton rat is underutilized, largely through historical accident. Continue reading

Happy Halloween! I want to tell you a scary story. A decade ago, the planet had six billion people. Today, according to the United Nations, we have seven billion. The UN has chosen Halloween as the symbolic day when the seventh billion person will come screaming into existence. Not scared yet? Maybe these words from environmental researcher Jonathan Foley will do the trick:

Happy Halloween! I want to tell you a scary story. A decade ago, the planet had six billion people. Today, according to the United Nations, we have seven billion. The UN has chosen Halloween as the symbolic day when the seventh billion person will come screaming into existence. Not scared yet? Maybe these words from environmental researcher Jonathan Foley will do the trick:

Right now about one billion people suffer from chronic hunger. The world’s farmers grow enough food to feed them, but it is not properly distributed and, even if it were, many cannot afford it, because prices are escalating. But another challenge looms.

By 2050 the world’s population will increase by two billion or three billion, which will likely double the demand for food, according to several studies. Demand will also rise because many more people will have higher incomes, which means they will eat more, especially meat. Increasing use of cropland for biofuels will put additional demands on our farms. So even if we solve today’s problems of poverty and access—a daunting task—we will also have to produce twice as much to guarantee adequate supply worldwide. Continue reading

I probably shouldn’t say this, but I love it when scientists occasionally throw all caution to the wind and clamber out on what seems a visibly shaky limb. Not of course, when they are offering up some new off-the-wall theory on autism or sudden infant death syndrome or flu vaccines—fields in which a little speculation could do a lot of harm. But in areas such as archaeology and palaeontology, a little derring-do on the far end of a branch can occasionally be a blessed relief—a reprieve, however short-lived, from a small mountain of papers that go on at numbing length on lithic use wear, say, or collared rim sherds, and neglect to inform the reader why these matter.

I probably shouldn’t say this, but I love it when scientists occasionally throw all caution to the wind and clamber out on what seems a visibly shaky limb. Not of course, when they are offering up some new off-the-wall theory on autism or sudden infant death syndrome or flu vaccines—fields in which a little speculation could do a lot of harm. But in areas such as archaeology and palaeontology, a little derring-do on the far end of a branch can occasionally be a blessed relief—a reprieve, however short-lived, from a small mountain of papers that go on at numbing length on lithic use wear, say, or collared rim sherds, and neglect to inform the reader why these matter.

All this came to mind recently when I came across research that an American palaeontologist presented this month at the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America. To make a long story short, Mark McMenamin, a palaeontologist at Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts, thinks he’s found fossil evidence for a kraken—a massive, predatory, tentacled beast from the deep that took down carnivorous ichthyosaurs the size of school buses during the Triassic Period.

The kraken was a creature of Norse mythology, a monster said to wrap entire Viking longships and knarrs in its loving embrace and drag them down to its ocean-bottom lair for a leisurely munch. McMenamin believes that he has found the lair of a real kraken—and not, I hasten to add, a mere garden-variety giant squid—in what is known as the Luning Formation at Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park in Nevada. Continue reading

A friend I run into regularly says, “Hey, Ann. Do you know that guy from around here who won that Nobel whatever?” He means Adam Riess, and yes, I know Riess. I’ve interviewed him, I say hello, he says hello back. “I have a question for you,” says my friend. “Is your Nobel guy really, really smart?” Of course Riess is really, really smart. I think about that. “But I don’t know that he’s smarter than other astronomers,” I say. And now I have to figure out how I know that astronomers are smart, given that I understand only a storified version of what they do; and though I try hard I don’t quite know how they think; and no, I’m not going to define “smart.” Continue reading

A friend I run into regularly says, “Hey, Ann. Do you know that guy from around here who won that Nobel whatever?” He means Adam Riess, and yes, I know Riess. I’ve interviewed him, I say hello, he says hello back. “I have a question for you,” says my friend. “Is your Nobel guy really, really smart?” Of course Riess is really, really smart. I think about that. “But I don’t know that he’s smarter than other astronomers,” I say. And now I have to figure out how I know that astronomers are smart, given that I understand only a storified version of what they do; and though I try hard I don’t quite know how they think; and no, I’m not going to define “smart.” Continue reading