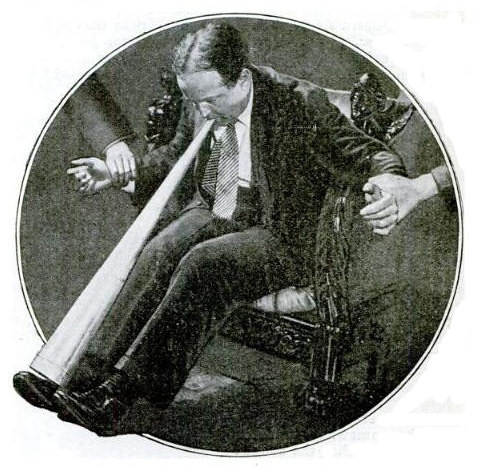

I always thought of Harry Houdini as a master trickster, fooling his audience into believing something had happened when, in fact, it had not happened. That’s not true. Houdini’s tricks — like escaping from a locked packing crate after it had been thrown into New York’s East River — were real. His “magic” was that nobody could figure out how he pulled them off.

I always thought of Harry Houdini as a master trickster, fooling his audience into believing something had happened when, in fact, it had not happened. That’s not true. Houdini’s tricks — like escaping from a locked packing crate after it had been thrown into New York’s East River — were real. His “magic” was that nobody could figure out how he pulled them off.

In the November 1925 issue of Popular Science, Houdini wrote an essay describing his obsession with the other kind of mystifiers: those who claim to have supernatural powers. Every day of his 35-year career, Houdini wrote, he had been thinking about psychics who supposedly communicate with the dead. He visited dozens of them and, as described at length in the essay, uncovered all of their lazy tricks. To give just one fun example, Houdini showed how mediums, during pitch-black seances, used trumpets controlled by their feet and mouths to produce voices that their audience believed to be ghosts.

Houdini did not consider himself a skeptic, but rather a public servant.

Continue reading