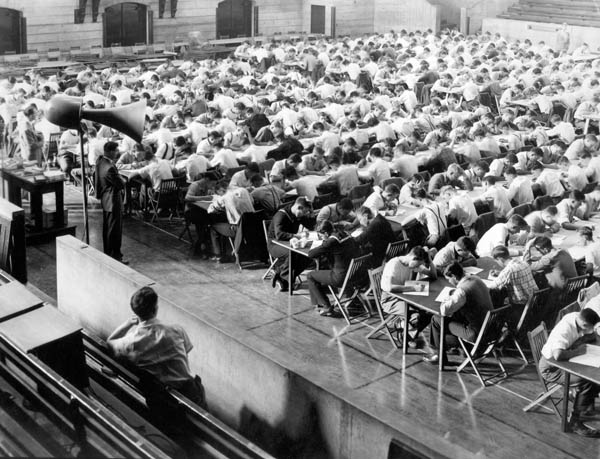

There’s only one thing more exciting than science, and that’s a science quiz! We’ll announce the winners in this year’s LWON Science Quiz in just a moment — remember, it was one prize for the best additional question submitted, and one for a random drawing from all the 100% correct answers. But first, a big thank you to all the many participants! The results were very interesting: almost all entrants scored 7, 8 or 9 correct answers, but only one entrant got all 10 answers correct.¹ We suspect this person is either a genius, or somehow managed to hack into the LWON Science Questions Database. Either instance is worthy of a prize, and all entrants are to be celebrated. And with no further ado, here are the correct answers: Continue reading

There’s only one thing more exciting than science, and that’s a science quiz! We’ll announce the winners in this year’s LWON Science Quiz in just a moment — remember, it was one prize for the best additional question submitted, and one for a random drawing from all the 100% correct answers. But first, a big thank you to all the many participants! The results were very interesting: almost all entrants scored 7, 8 or 9 correct answers, but only one entrant got all 10 answers correct.¹ We suspect this person is either a genius, or somehow managed to hack into the LWON Science Questions Database. Either instance is worthy of a prize, and all entrants are to be celebrated. And with no further ado, here are the correct answers: Continue reading

This year’s Nobel Prize in Physics was, in a way, a foregone conclusion. The 1998 discovery by two teams of scientists that the expansion of the universe is accelerating—under the influence of something that scientists have shruggingly come to call dark energy, which later studies have revealed to comprise 72.8 percent of the universe—was one that everybody assumed would win the Prize. It was only a matter of when.

This year’s Nobel Prize in Physics was, in a way, a foregone conclusion. The 1998 discovery by two teams of scientists that the expansion of the universe is accelerating—under the influence of something that scientists have shruggingly come to call dark energy, which later studies have revealed to comprise 72.8 percent of the universe—was one that everybody assumed would win the Prize. It was only a matter of when.

Only somewhat less foregone was who would receive the Prize for the discovery. The leaders of the two discovery teams—Saul Perlmutter, of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and Brian Schmidt, of the Australian National University Mount Stromlo Observatory—were shoo-ins. As the lead author on Schmidt’s team’s discovery paper, Adam Riess, a postdoc at the University of California, Berkeley, at the time of the discovery (now an astronomer at Johns Hopkins University), stood perhaps—perhaps—slightly less of a chance, but the difference was in the nature of a four- versus a five-sigma result.

Even the allocation of the award was more or less foregone. Perlmutter would get half of the 10 million Swedish kroner ($1.44 million) prize, and either Schmidt would get the other half or he would split it with Riess. The latter scenario—50/25/25—is indeed what the Solomons of Stockholm decreed, and this past Saturday the three new laureates received their medals from His Majesty King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden.

Yet in the two months since the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced the Prize, on October 4, many members of the discovery teams have found themselves experiencing what one astronomer described to me, via e-mail, as “a bag of mixed emotions.”

The problem isn’t that the wrong persons won. The problem is that the right persons didn’t.

There is an old story about a scorpion and a turtle. Variants abound, but the basic tale revolves around an unusually talkative scorpion that asks a turtle for a lift across a river. The turtle refuses at first, fearing the scorpion’s sudden but inevitable betrayal. The scorpion insists, the turtle relents, and the two get halfway across before the scorpion predictably stings the turtle. As they sink to their mutual deaths, the turtle asks, “Why did you do it?” The scorpion simply replies: “It’s my nature.”

There is an old story about a scorpion and a turtle. Variants abound, but the basic tale revolves around an unusually talkative scorpion that asks a turtle for a lift across a river. The turtle refuses at first, fearing the scorpion’s sudden but inevitable betrayal. The scorpion insists, the turtle relents, and the two get halfway across before the scorpion predictably stings the turtle. As they sink to their mutual deaths, the turtle asks, “Why did you do it?” The scorpion simply replies: “It’s my nature.”

This story is similar, except an octopus plays the role of the scorpion, and no one talks. Continue reading

In the rural Rocky Mountains where I live, we disagree about a lot of things — politics, religion, water, Tim Tebow — but we all agree on aspen. We love them, especially when they turn blaze-yellow in the fall, and we’d like them to stick around. So in 2004, when aspen throughout the Rockies started dying wholesale, the public reaction was fierce. What the heck was happening to our trees?

Since 2008, the dieoff has slowed, but so-called sudden aspen decline, or SAD, has hit nearly one-fifth of the aspen stands in the Rockies. It turns out that the aspen decline was driven by drought — namely a prolonged, region-wide dry spell that peaked in the early 2000s, and is thought to be a harbinger of the more frequent and severe droughts expected as the climate changes. In a grim sign of the times, though, it’s no longer enough to know why the trees are dying. In order to predict future die-offs, it’s important to know how.

2011 is drawing to a close, and what a big year it was…for science! Many interesting and important scientific things occurred, and we hope you were paying attention, because here’s your chance to test your knowledge of the most notable scientific developments of 2011 with our super-scientific end-of-the-year quiz!

2011 is drawing to a close, and what a big year it was…for science! Many interesting and important scientific things occurred, and we hope you were paying attention, because here’s your chance to test your knowledge of the most notable scientific developments of 2011 with our super-scientific end-of-the-year quiz!

Did you know you can win actual prizes in our quiz? That’s right! You can be the proud owner of a stylish faux-styrofoam eco-cup OR a one-of-a-kind t-shirt!

Here’s how:

Answer the questions below and email your answers to lwonquiz@gmail.com. We will choose a winner by random drawing among all the correct entries.

OR

Add your own quiz question and answer and put it in the comments! You must write a question AND add four answer choices. The best question wins a prize!

Tom will announce the correct answers and winners on Friday. All entries must be received by 11:59 PM on Wednesday, December 14.

Good luck!

Erika and Tom

1. Scientists sparred over a claim that what was incorporated into DNA? Continue reading

In October, 2006, I wrote a story that began like this . . .

In October, 2006, I wrote a story that began like this . . .

“In a hangar-sized building at the University of Maryland, Dan Lathrop is playing God. He and his students are cobbling together a three-meter titanium ‘earth’ that—when spun—they hope will give birth to a magnetic field similar to that generated by the larger sphere beneath our feet.”

I was in graduate school for science writing then, and the story was an assignment for my news writing class. My professor, NPR’s David Kestenbaum, had arranged a field trip to see Lathrop’s sphere. My classmates and I spent a few hours nosing around his lab. We called an outside source or two, and wrote our best approximations of a news story. To the best of my knowledge, our stories were never published. I never even sent a pitch. I was too scared.

Even then, Lathrop’s sphere wasn’t exactly hot news. Naomi Lubick wrote a story for Geotimes magazine in 2004. “Dan Lathrop is building a planet in his lab. He custom-ordered a 3-meter-tall metal sphere, which will perch inside a metal box built in his brick-walled lab at the University of Maryland in College Park,” she begins. Continue reading

As I write this, 15,000 delegates from around the globe have congregated in Durban, South Africa to take part in a magisterial game of pretend. Officially called the 17th session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 17) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, this recurring charade provides an opportunity for scientists and citizens threatened by climate change to give impassioned speeches about the urgency of the climate problem while representatives from the world’s biggest emitters pretend (or not) to listen before refusing to agree upon any meaningful action.

As I write this, 15,000 delegates from around the globe have congregated in Durban, South Africa to take part in a magisterial game of pretend. Officially called the 17th session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 17) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, this recurring charade provides an opportunity for scientists and citizens threatened by climate change to give impassioned speeches about the urgency of the climate problem while representatives from the world’s biggest emitters pretend (or not) to listen before refusing to agree upon any meaningful action.

COP17 continues through December 12, but no one expects it to yield any significant agreements. That’s not to say that it won’t have an effect on the climate. According to the Telegraph, COP17’s carbon footprint is estimated to reach 15,000 tons of CO2 equivalent, and that’s without considering what may be the meeting’s biggest carbon source — the flights attendees take to and from Durban. All told, the Telegraph estimates that COP17’s carbon footprint will reach something akin to “the annual footprint of a small African country.” Continue reading

A few weeks ago I read the November 2011 newsletter of Roll Back Malaria – a partnership sponsored by the World Health Organization, the United Nations and the World Bank. It contained the following headline: “Nearly a third of all malaria affected countries on course for elimination over the next decade.” I’m not saying the glass is half empty, but it’s just not that simple.

A few weeks ago I read the November 2011 newsletter of Roll Back Malaria – a partnership sponsored by the World Health Organization, the United Nations and the World Bank. It contained the following headline: “Nearly a third of all malaria affected countries on course for elimination over the next decade.” I’m not saying the glass is half empty, but it’s just not that simple.

In this short sentence RBM conjured images of great progress against the world’s millennia-old malaria pandemic. So it may sound like nit-picking to point out that RBM’s list includes mostly economically developing countries that should have eliminated malaria a long time ago (former Soviet Republics; Turkey; Sri Lanka; North Korea; sub-regions of Indonesia, Thailand, India, China and Bhutan; several Pacific Islands; countries of the Middle East and North Africa; and from the Western Hemisphere, Mexico, Argentina and Paraguay). Add that not making the list are the world’s most malaria-burdened countries, all in sub-Saharan Africa – where 85 percent of the world’s infections and 90 percent of all malaria-related deaths take place – and I think a case can be made that RBM perhaps missed the mark.

For me, the RBM report that inspired the headline really highlights that global health programs are fighting two malarias and making great progress against only one of them. Continue reading