This is how it happens for me: I’m completely asleep, and then something terrible creeps across the room, reaches spindly, pincer-like fingers for my hand, and pinches. That pinch is what wakes me up in terror, gasping and whimpering and trying desperately to pull my arm under the covers. But I can’t. I can’t do anything because no matter how I struggle, I can’t move a muscle. The light in the room is slanted so wrong it makes my skin crawl and all I can do is feel that thing hovering there, grinning horribly just beyond my field of view. I’ve tried to scream but my voice doesn’t work either. The only sound I’m capable of is a dog-pitched whine. The thing doesn’t leave until I lose consciousness.

I didn’t know this the first couple of times it happened, but my experience is by no means unique. It goes by many names, known variously as night terrors, the incubus, witches’ pressure and Old Hag syndrome. It happens when a few important wires get crossed in your brain and you accidentally wake up in the middle of dreaming. Old Hag syndrome is usually explained away as an evolutionary hiccup, a terrifying but harmless side effect of a mechanism that evolved to protect you. But the story might be a bit more complicated than that. In one case, those night terrors may have led to a series of deaths. Luckily, if you’re like me and the Old Hag plagues you, there are ways to fight her off. Continue reading

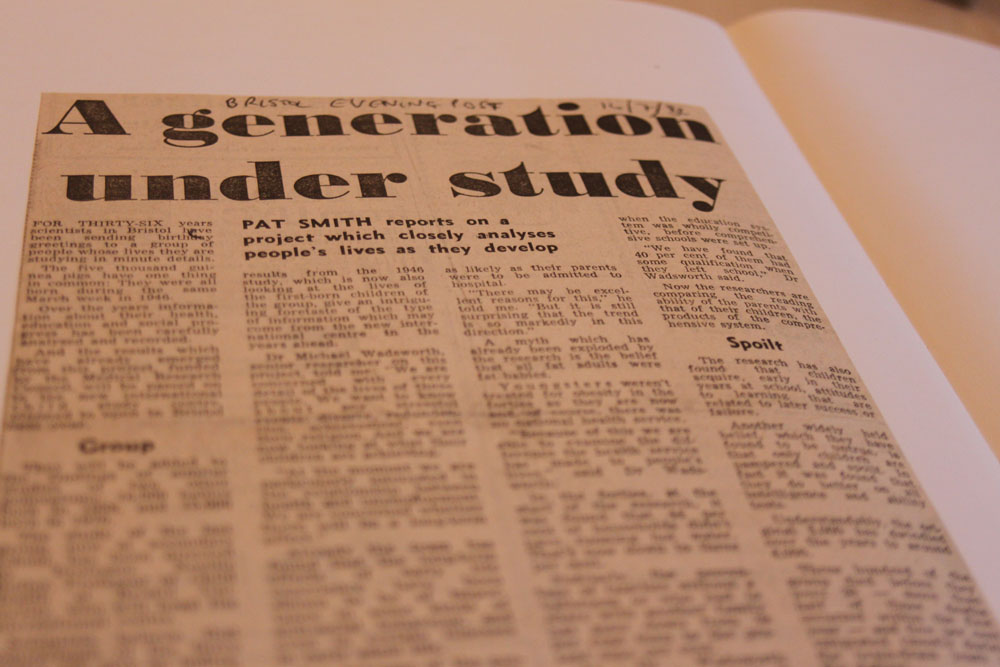

Britain in March 1946 was a dank, hungry, but optimistic place as people grappled with winter, rationing and the aftermath of World War 2. It was also the time that the country gave birth to something historically and scientifically remarkable. 13,687 babies born during one March week were weighed, measured and enrolled into what has, today, become the longest running study of human development in the world.

Britain in March 1946 was a dank, hungry, but optimistic place as people grappled with winter, rationing and the aftermath of World War 2. It was also the time that the country gave birth to something historically and scientifically remarkable. 13,687 babies born during one March week were weighed, measured and enrolled into what has, today, become the longest running study of human development in the world.