Granted that Abstruse Goose is being a little juvenile — I prefer to think of him not as immature but just young — and certainly Galileo occasionally had non-astronomical thoughts, even if AG is making them up. But the writing and the drawing of Jupiter and its little stars, its “stellae,” Galileo called them, are all real. At least I think they are. I’m not going to admit how much time I spent trying to find this exact writing and drawing in Galileo’s notebooks, which he called Observations. I can’t find them. The writing matches Galileo’s and Galileo drew the stellae that way, so I don’t think AG made them up too. You try, here.

Granted that Abstruse Goose is being a little juvenile — I prefer to think of him not as immature but just young — and certainly Galileo occasionally had non-astronomical thoughts, even if AG is making them up. But the writing and the drawing of Jupiter and its little stars, its “stellae,” Galileo called them, are all real. At least I think they are. I’m not going to admit how much time I spent trying to find this exact writing and drawing in Galileo’s notebooks, which he called Observations. I can’t find them. The writing matches Galileo’s and Galileo drew the stellae that way, so I don’t think AG made them up too. You try, here.

[UPDATE: No, don’t try. With the formidable help of Google Translate, I have belatedly concluded that in fact not only did AG imitate Galileo’s handwriting, he made up the sentences too. I still think the part below the stellae is real but I’m not betting on it. AG himself is pretty formidable: not everybody can talk dirty in Latin.]

Meanwhile, you know how the story ends but Galileo was, if nothing else, a superb grant writer and I thought you’d like it in his own words:

“Here we have a fine and elegant argument for quieting the doubts of those who, while accepting with tranquil mind the revolutions of the planets about the sun in the Copernican system, are mightily disturbed to have the moon alone revolve about the earth and accompany it in an annual rotation about the sun. Some have believed that this structure of the universe should be rejected as impossible. But now we have not just one planet rotating about another while both run through a great orbit around the sun; our own eyes show us four stars which wander around Jupiter as does the moon around the earth, while all together trace out a grand revolution about the sun in the space of twelve years.”

He closes the argument: “Time prevents my proceeding further, but the gentle reader may expect more soon.”

______

http://abstrusegoose.com/414

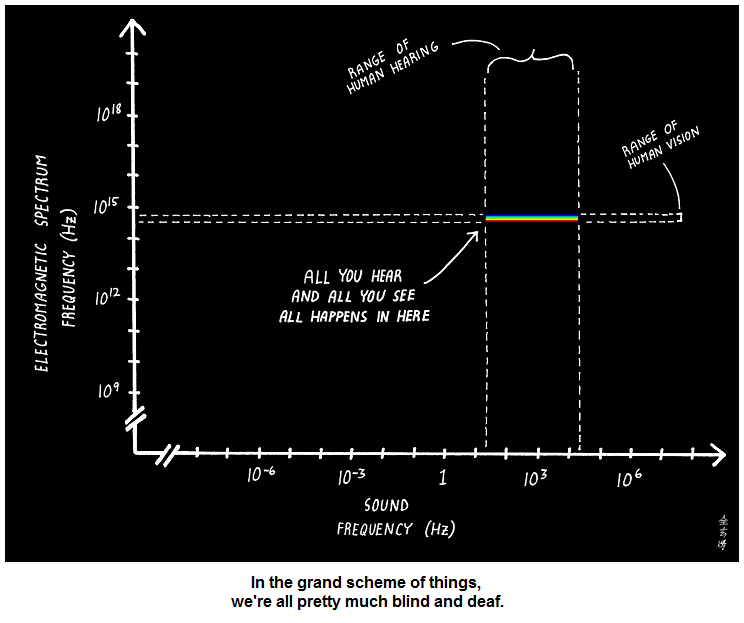

That vertical axis — the electromagnetic spectrum which is science-talk for light — actually goes from something like 3 x 102 to something like 3 x 1024 (in the same units), which is from radio waves, through microwaves, to infrared, to the visible (that tiny rainbow window there), to the ultraviolet, to xrays, to gamma rays.

That vertical axis — the electromagnetic spectrum which is science-talk for light — actually goes from something like 3 x 102 to something like 3 x 1024 (in the same units), which is from radio waves, through microwaves, to infrared, to the visible (that tiny rainbow window there), to the ultraviolet, to xrays, to gamma rays.