**

The new study, certainly not the last word on DNA, was published last week in The EMBO Journal. The music is Chopin’s Minute Waltz, the subject of another post.

**

The new study, certainly not the last word on DNA, was published last week in The EMBO Journal. The music is Chopin’s Minute Waltz, the subject of another post.

Science or music, music or science? Too often when it comes to science-inflected tunage, that’s the choice one has to make.

Science or music, music or science? Too often when it comes to science-inflected tunage, that’s the choice one has to make.

The best songs, usually, are only tangentially about science. The Low Anthem’s “Charlie Darwin,” for example, is stirringly beautiful, and improves with each listen well into the hundreds. But poor old Darwin doesn’t ever rise above the level of metaphor — and there’s certainly no mention of his long decade spent immersed in the painstaking study of barnacle systematics.

At the other end of the spectrum, any number of recent lab-based music videos — the “Large Hadron Rap,” “Bad Project” — have been full of fun and verifiable science content. But oh dilly, are they nerdy. And musically, they don’t rise above the level of novelty acts.

That’s what makes Nimbleweed so darned special. After the jump: quite possibly the best science songs you’ve ever heard. Continue reading

A week ago, I found myself sitting in a small phlebotomy room at the back of my doctor’s office. Had you been a fly on the wall, this is what you would have observed: On one side of me stood a young nurse holding a hollow needle and a glass tube with a brown rubber stopper. On the other side stood my doctor, a jovial gray-haired fellow. My left hand limply grasped the doctor’s right middle and index fingers. I was weeping.

A week ago, I found myself sitting in a small phlebotomy room at the back of my doctor’s office. Had you been a fly on the wall, this is what you would have observed: On one side of me stood a young nurse holding a hollow needle and a glass tube with a brown rubber stopper. On the other side stood my doctor, a jovial gray-haired fellow. My left hand limply grasped the doctor’s right middle and index fingers. I was weeping.

“Squeeze them,” he said, as the nurse plunged the needle into my arm. “Squeeze them as hard as you need to.” Behind his voice lurked desperation. “You’re not squeezing. Go ahead and squeeze!” Presumably he was referring to his fingers. But I didn’t want to squeeze. I wanted to die. I wanted the doctor to go away and leave me alone with my misery. I wanted the torture to end. I wanted the floor to open up and swallow the whole goddamn lab.

The needle was in and it hurt. The bloodletting was taking forever. I began to hyperventilate. Dr. Feelgood tried another tack. “Can you count to five in Spanish?” he asked. I can. In fact, I’m fluent in Spanish. But that moment seemed like a bad time for a language lesson. “Not right now,” I replied. The good doctor could not be dissuaded. He began to sing. “Uno, dos, tres amigos. Cuatro, cinco, seis amigos!”

For those who don’t know, “Uno, Dos, Tres Amigos” is a children’s song popular with the five and under crowd. I am thirty-three. If I hadn’t been sobbing, I might have laughed. Finally the needle came out. The doctor disappeared. The nurse apologized. I fished a crumpled tissue out of my pocket and wiped my wet cheeks and nose. And then I got the hell out of there.

You may have gathered by now that I have an extreme fear of needles, a disorder known as belonephobia. Continue reading

This is the universe at present. You’re seeing not the light but the dark — you knew that most of the universe’s matter is dark, right? — and its motions. Not until the far right end are you seeing the light. Go ahead and clickety click all over this; zoom it in and out, drag it around. It’s a computer simulation based on and ending with observed reality. But it doesn’t read from left to right; it’s less the chronology of the universe’s life than a series of its aspects. It’s so beautiful you might faint. Continue reading

Several years ago, on a soggy but majestic mountain afternoon, I hiked into the Yosemite backcountry to meet UC-Berkeley mammalogist Jim Patton. Patton and his colleagues at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology were retracing the steps of renowned naturalist Joseph Grinnell, who surveyed California’s wildlife early in the last century — and obsessively documented his work in voluminous, barely legible field journals. (Fellow archive nerds, see some wonderful examples here.)

Thanks to Grinnell’s tireless note-taking, Patton and his team were able to repeat the surveys, and get a sense of how Yosemite’s wildlife has changed over the past 90 years. Of the 30 mammal and bird species studied by both Grinnell and the modern-day Berkeley team, 14 show no significant change in their range, but 16 have shifted their habitats, with lower-elevation species consistently expanding their range uphill and higher-elevation species — the pika, the alpine chipmunk — retracting the lower limit of their range. The pattern suggests that many of Yosemite’s critters are already responding to climate change, and habitat models developed by the researchers strengthened this conclusion.

But that’s not the end of Grinnell’s legacy.

This week, we all showed a bit of ankle to commemorate Valentine’s Day (well, Cassie showed her toes)

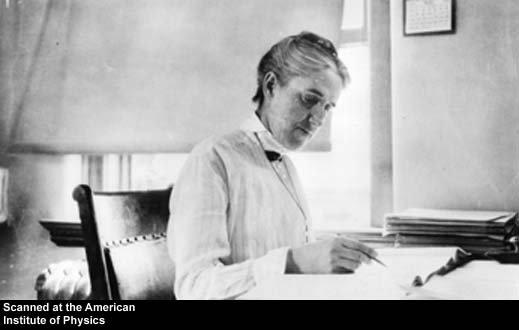

Guest poster Sarah Zielinski told us what we’ll find in “Pickering’s Harem”

Richard got punked by Tom Cruise while explaining the differences (and similarities) between show biz and science

Hogan faced Hayden in an LWON Battle Royale (okay, the battle was to see who could be more accommodating and polite but STILL! CAGE MATCH!)

And LWON pal Abstruse Goose demonstrated the plight of an over-specialized molecular biologist

Extra credit: A lifelike horse head mask

See you Monday!

By the late 1800s, astronomy had moved on from simple human observation to the collection of images of the sky on photographic plates — pieces of glass coated with light-sensitive silver salts. At the time they were made, these plates could be analyzed only through tedious, labor-intensive work. A person had to scan and measure and compare stars in the images before their position and brightness could be calculated and discoveries made.

By the late 1800s, astronomy had moved on from simple human observation to the collection of images of the sky on photographic plates — pieces of glass coated with light-sensitive silver salts. At the time they were made, these plates could be analyzed only through tedious, labor-intensive work. A person had to scan and measure and compare stars in the images before their position and brightness could be calculated and discoveries made.

In 1879, Edward Pickering, head of the Harvard College Observatory, began hiring women to do this work. Paid just 25 to 30 cents an hour for their labors, women were cheaper than men, but Pickering found that they were also better than the male scientists who had done the work previously. The women were more detail-oriented and worked harder. (That didn’t mean they were more respected, however. Today this group of women is often called the “Harvard Computers,” but when they were working they were called “Pickering’s Harem.”) One of the computers was Henrietta Snow Leavitt. Continue reading

The magician Todd Robbins eats light bulbs. For a while last year he practiced his brand of indigestitation in an off-Broadway show on magic and murder, Play Dead. Most of the production was in the tradition of Ricky Jay’s several one-man meditations on the history of hokum. The one exception came early in the show (since closed), when Robbins put a light bulb into his mouth, bit down, and kept biting down until the glass part of the bulb was gone. He asked a woman in one of the first rows if she believed that he’d really eaten the bulb. “No,” she said. He looked slightly crushed, then tried again: He really had eaten the bulb. Really! Now did she believe him? “No.”

I happened to know, through a mutual friend, that Robbins does eat light bulbs. There isn’t a trick to doing it, but there is a technique, and he’s mastered it. (It requires “eating the glass so that it is sufficiently masticated and pulverized to get through his system,” the show’s co-writer and director Teller, of Penn and Teller, told The Wall Street Journal). But how do you convince an audience watching a show full of illusions that the stranger-than-fiction thing they’ve just seen is real?

I’ve been thinking about that light bulb for the past few weeks, ever since I saw a trailer for Mission: Impossible—Ghost Protocol (who says the masses aren’t ready for esoteric, but correct, punctuation?). I watched Tom Cruise cling, katydid-style, to the side of a skyscraper, then rappel down, or up, or sideways, or something. Whatever it was he was doing, I knew he wasn’t doing it. Computer Generated Imagery (CGI) was doing it. Even if Tom Cruise himself sat down next to me in the movie theater and insisted that it was really him rappelling down the side of the skyscraper—really!—I wouldn’t have believed him.*

Yet I believe that humans are descended from primordial sludge, that “empty” space is filled with a quantum froth of virtual particles popping into and out of existence (or “existence”), that the universe is expanding, and that 96 percent of the mass-energy density of the universe is in a form that we as a species have never seen.