As a science journalist, I sympathize with book reviewers who wrestle with the question of whether to write negative reviews. It seems a waste of time to write about a dog of a book when there are so many other worthy ones; but readers deserve to know if Oprah is touting a real stinker.

As a science journalist, I sympathize with book reviewers who wrestle with the question of whether to write negative reviews. It seems a waste of time to write about a dog of a book when there are so many other worthy ones; but readers deserve to know if Oprah is touting a real stinker.

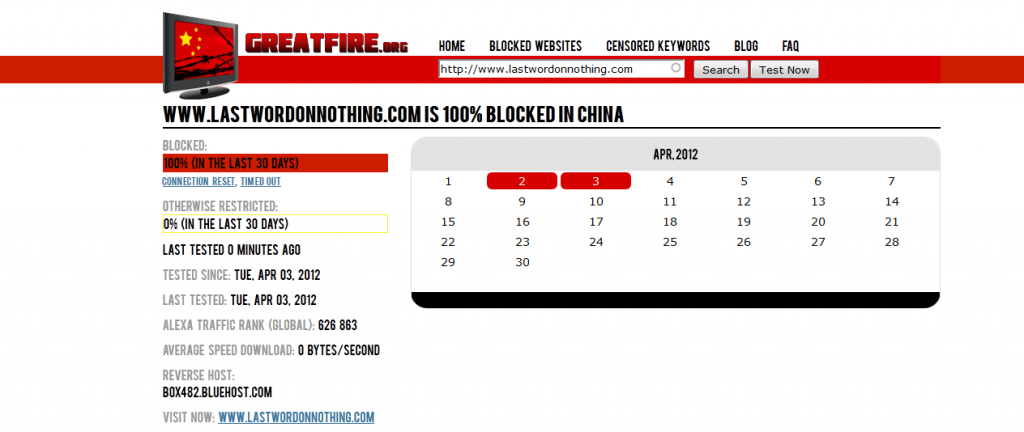

On 2 April, Science Translational Medicine published a study on DNA’s shortcomings in predicting disease. My editors and I had decided not to cover the study last week after we saw it in the journal’s embargoed press packet, because my sources offered heavy critiques of its methods. But it was a tough choice: we knew the paper was bound to get a lot of other coverage, as it conveyed a provocative message, would be published in a prominent journal, and would be highlighted at a press conference at the well-attended annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research. Its lead authors, Bert Vogelstein and Victor Velculescu of the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center in Baltimore, Maryland, are also leaders in the cancer genetics field.

I ended up writing about the paper anyway after it made a huge media splash that prompted fury among geneticists. In a thoughtful post at the Knight Science Journalism tracker, Paul Raeburn asked yesterday why other reporters didn’t notice the problems with the study that I wrote about. Having been burned by my own share of splashy papers that go bust, I think the “limits of DNA “ story underscores a few broader issues for our work as science journalists:

This past weekend I spent too many hours on Netflix watching

This past weekend I spent too many hours on Netflix watching