This past weekend I spent too many hours on Netflix watching Lie to Me, the Fox television drama that ran from 2009 to 2011. It’s a crime procedural (my favorite genre) about Dr. Cal Lightman, a psychologist who can spot liars by analyzing their body language and super-fast facial ticks, called microexpressions.

This past weekend I spent too many hours on Netflix watching Lie to Me, the Fox television drama that ran from 2009 to 2011. It’s a crime procedural (my favorite genre) about Dr. Cal Lightman, a psychologist who can spot liars by analyzing their body language and super-fast facial ticks, called microexpressions.

On the show, Lightman’s obsession with faces stems from a decades-old film of his mother recorded by her therapist. She had been institutionalized for depression, but on the film, she tells the therapist how good she feels after treatment, and how she longs to see her children. The therapist is convinced, allows her to go home, and she promptly commits suicide. After years of analyzing the footage, Lightman discovers that his mother’s face had shown flashes of agony while she lied about her happiness. He goes on to create a system for coding subtle facial expressions and launches a consulting firm, The Lightman Group, that helps police (and all sorts of other clients) detect when individuals are lying, and why.

It’s one of those shows that sticks with you, or with me, anyway. For the past few days I’ve been surreptitiously scrutinizing the faces of everyone I see—people exchanging small talk at a birthday party, people telling outrageous true stories on stage, my longtime friends, even my fiancé. Could I discover their hidden feelings just by paying closer attention? It’s tricky, of course, when you don’t know if someone is lying. But what about when you do know, like in the sad case of Mike Daisey?

Yesterday I hatched a plan: Learn the basics of the real science behind Lie and Me, then watch a bunch of old Daisey clips on YouTube and root out the signs of his deception.

Continue reading →

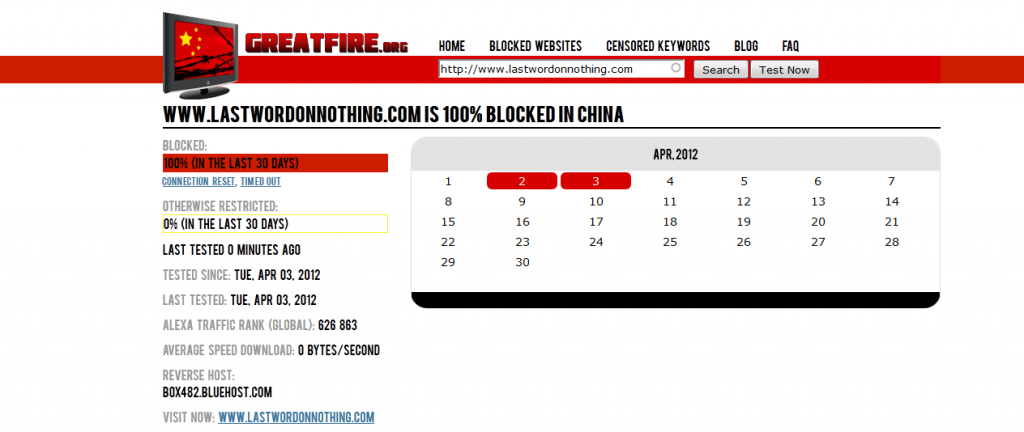

If you were sitting in front of a computer in China right now, you wouldn’t be reading this. Nor would you have seen Cameron’s post about a snail invasion on Monday or Michelle’s piece yesterday on a poem inspired by Marie Curie. In fact, when you tried to open our website, your computer would have heaved and roiled and finally timed out. After several tries, you would have likely concluded that we had server problems and eventually crossed us off your list.

If you were sitting in front of a computer in China right now, you wouldn’t be reading this. Nor would you have seen Cameron’s post about a snail invasion on Monday or Michelle’s piece yesterday on a poem inspired by Marie Curie. In fact, when you tried to open our website, your computer would have heaved and roiled and finally timed out. After several tries, you would have likely concluded that we had server problems and eventually crossed us off your list.

This past weekend I spent too many hours on Netflix watching

This past weekend I spent too many hours on Netflix watching