I spent the past two days at the Science Writing in the Age of Denial conference at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The event explored the phenomenon of denial and what it means for science writers. How can journalists effectively convey science when its uncomfortable truths face organized resistance? Continue reading

I’d like to be a mother—someday. Now is not a good time. I’m 28 years old, unmarried, and trying to build a freelance writing business from a small New York apartment.

I grew up in the wake of the feminist movement, and boy am I glad about that. Gender inequalities still exist, of course (ahem). But since grade school, my parents, teachers and favorite after-school-TV-show characters have encouraged me to invest in my education and career, just like any ambitious man. And I have.

Alas, biology still holds a trump card: my closing fertility window. By the time I’m 38, my bank account may be pregnant, but my eggs will be fossils. In last week’s issue of New Scientist, I wrote about a far-out experimental solution: freezing pieces of my ovary. The premise of the story was that if this technology ever gets off the ground, it could fulfill the original promise of the birth control pill, allowing women to make career decisions without the pressure of a ticking clock.

And it’s such a satisfying premise, isn’t it, especially for science-loving feminists like me. But after five months of airing it, triumphantly, to everyone I know, and thinking about their responses, my enthusiasm has waned. The cultural limits on the age of motherhood, I’m afraid, are far stronger than the biological ones.

Continue reading

When I stepped back from full-time writing a few years ago, I knew that I would be giving up something I loved for something I felt was crucially important. But I had no idea what I would gain by making teaching, at Stanford University, a big part of my work life. In fact, I’m still discovering that now.

When I stepped back from full-time writing a few years ago, I knew that I would be giving up something I loved for something I felt was crucially important. But I had no idea what I would gain by making teaching, at Stanford University, a big part of my work life. In fact, I’m still discovering that now.

I’ll mumble on about writing and teaching and the nature of joy in a moment, but the real reason for this post is to link here:

Go ahead, check it out. I won’t even mind if you don’t come back. You see, I’ve learned that when teaching really works out, I’m just as happy to have you spend time with my students’ work as with my own. Continue reading

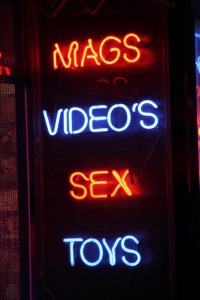

Michelle interviews a copy editor at a porn magazine — yes, porn magazines do have copy — and asks the immortal question, Is that an apostrophe in your pocket?

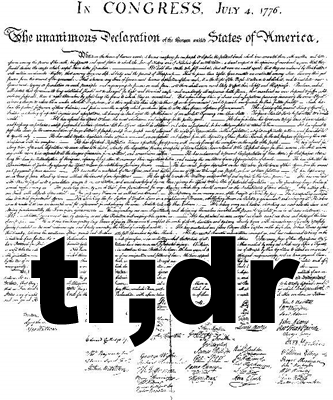

Sally considers dimwit webtalk, in particular tl;dr, and wonders whether “you’re” is going the way of “forsooth,” and suspects it might be and not a moment too soon.

Biology writer Erika talks to physics writers to find out how far to trust those physicists: pretty far, unless they’re being political or human.

Jessa goes to the exhibit of photos from the Shackleton expedition and sees lies, damned lies, and the irresistibility of a story.

Heather sees the ingenuity of ancient humanity: killing whales with little blue buttercups.

Each July, along the dappled stream banks of Kodiak Island, just off the Alaska coast, a weedy looking wildflower produces a few dark-blue hooded blossoms. There is nothing particularly memorable about the appearance of Aconitum delphinifolum. Its leaves are thin and rather spiky. Its scrawny-looking stem cannot hold the weight of its flowers: its neighbors keep it upright. But this eminently forgettable looking plant, a member of the buttercup family, possesses a dark secret. Aconitum delphinifolum contains a toxin capable of killing one of the world’s largest animals, a 40-ton humpback whale. Indeed, the local Alutiiq people have long understood this: their whalers once enlisted it as a lethal weapon. Continue reading

Each July, along the dappled stream banks of Kodiak Island, just off the Alaska coast, a weedy looking wildflower produces a few dark-blue hooded blossoms. There is nothing particularly memorable about the appearance of Aconitum delphinifolum. Its leaves are thin and rather spiky. Its scrawny-looking stem cannot hold the weight of its flowers: its neighbors keep it upright. But this eminently forgettable looking plant, a member of the buttercup family, possesses a dark secret. Aconitum delphinifolum contains a toxin capable of killing one of the world’s largest animals, a 40-ton humpback whale. Indeed, the local Alutiiq people have long understood this: their whalers once enlisted it as a lethal weapon. Continue reading

As I’ve been thinking about the challenges facing science journalism, a little voice in my head has been murmuring, “Yes, but isn’t all this navel-gazing a bit biology-centric?”

Number one on my list of lessons from the “limits of DNA” story is that datasets are getting bigger, and few of us reporters are well-equipped to cope with the statistics behind analysis of these datasets on our own. But datasets in physics have been huge for a long time now. And while it’s definitely becoming more difficult to trust traditional scientific authorities in biology and biomedicine due to the splintering of disciplines and the struggle for funding, some of the forces that are driving fierce competition in biology don’t apply to physics. Physicists don’t have to pretty up their data to try to win drug approvals, for instance.

But I only know what I do, and all I do is biology. So I asked a highly unscientific sample of my favorite physics reporters and writers (n=4) what they thought about these issues. And what I learned surprised me.

Spend enough time on the internet and you’ll spot one. They tend to sprout in the comments beneath articles like little text cabbages:

Spend enough time on the internet and you’ll spot one. They tend to sprout in the comments beneath articles like little text cabbages:

tl;dr

tl;dr

tl;dr

Unpack them and you’ll find an accusation: “too long; didn’t read.”

This isn’t some hot new trend I’m cluing you into: tl;dr hasn’t been de rigeur since it became Urban Dictionary’s word of the day in 2005. Unlike most slang of the moment, however, over the past seven years, it has proliferated. Its enduring popularity and ubiquity is a testament to the fact that this concise little construction calls out what might be the fundamental problem of the internet age. As such, tl;dr is the battle cry of the internet generation. And the concise way it encapsulates the problem might also be a hint to its ultimate solution.

Oh, are you having a bad day? JUST BE GLAD YOU’RE NOT A BIRD. Because if you were a bird, as Ann points out, you would go through puberty every single year of your life. Nature, Ann correctly summarises, is one mean mother.

Maybe you’re just irritable because people keep noisily eating and clinking their silverware around you. Cassie takes a fascinating look at the making of a nascent new disorder. Is there really such a thing as misophonia or are there just really prickly individuals?

But don’t worry: your mood won’t stay gloomy for long when you read Christie’s life-changing news that there is a Spam Poetry Institute. “I am a wandering English” needs to be shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot prize.

And Heather warms our hearts some more with the tale of kindly, gentle St. Death, who accepts all those cast out by the Catholic Church–from gay men and women to drug dealers and prostitutes and people who kill legitimate scientific enterprise–and is said to work miracles on their behalf.

And now you’re ready to read Richard’s unraveling of the ultimate cosmological paradox.

Extra credit: So you figured out how to unravel the head-asploding multiverse paradox. YAWN. How about explaining why homochirality implies planets ruled by advanced monster dinosaurs? The ball, Panek. It is in your court.