I first encountered lionfish on Carrie Bow Cay, a hurricane-battered scrap of an island 15 miles off the coast of Belize. The rotating crew of biologists on Carrie Bow work hard and play hard, and one popular form of play is lionfish hunting: spearing, cooking, and enthusiastically devouring these stripey fellows on the left. Lionfish are a troublesome invasive species, probably introduced to the Caribbean through the aquarium trade (but probably not, as is often rumored, via a beachside aquarium smashed by Hurricane Andrew). So the Carrie Bow pastime is not only tasty — fans of grilled lionfish told me it tastes like a cross between snapper and grouper — but also morally uplifting.

I first encountered lionfish on Carrie Bow Cay, a hurricane-battered scrap of an island 15 miles off the coast of Belize. The rotating crew of biologists on Carrie Bow work hard and play hard, and one popular form of play is lionfish hunting: spearing, cooking, and enthusiastically devouring these stripey fellows on the left. Lionfish are a troublesome invasive species, probably introduced to the Caribbean through the aquarium trade (but probably not, as is often rumored, via a beachside aquarium smashed by Hurricane Andrew). So the Carrie Bow pastime is not only tasty — fans of grilled lionfish told me it tastes like a cross between snapper and grouper — but also morally uplifting.

It was a usual week at LWON: questions and opinions shot off like bottle rockets, unexpectedly and in all directions.

It was a usual week at LWON: questions and opinions shot off like bottle rockets, unexpectedly and in all directions.

Virginia gets on the phone to interview neuroscientists and realizes that most of them are men. Then she gets on the phone about a hot new neuroscience and realizes that almost-most of her interviewees are women. Why is that? Social fluidity? Role models? Avoidance of the dick factor?

Cassandra watches earthworms having sex. She wears a headlamp. She takes pictures. Why didn’t she know about this? She interviews earthworm-sex experts. She finds out.

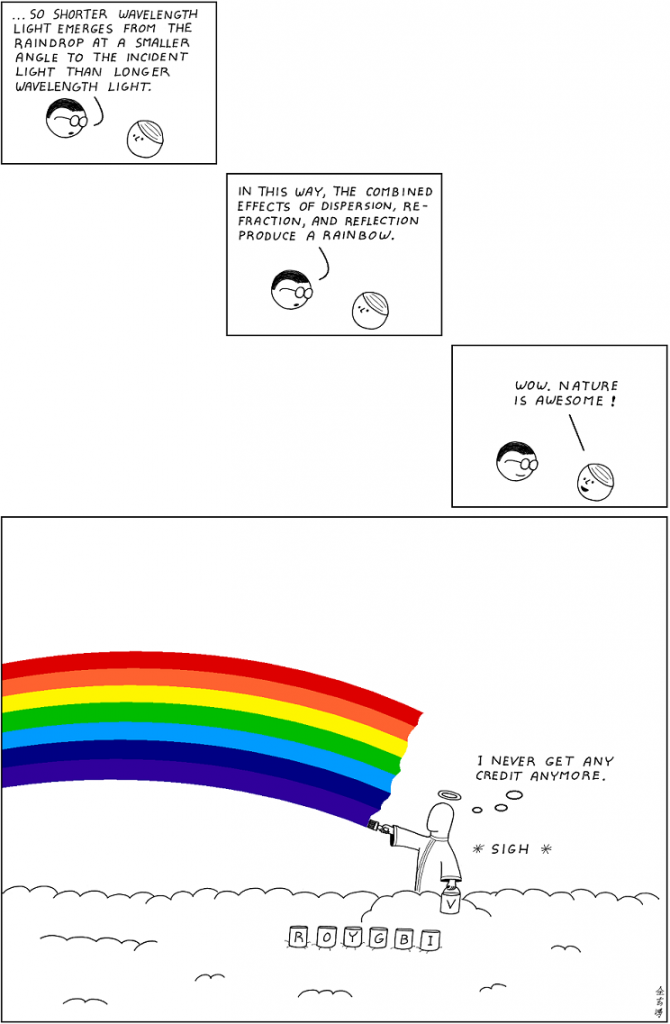

Abstruse Goose gets righteously pissy on behalf of the creator of rainbows.

Michelle wants to know how, in a conversation the length of an elevator ride, to sum up scientists’ “thoroughly conscious ignorance.”

Ann’s Uncle Bundy shows her some ball bearings he thinks are pretty and 40 years later, she figures out why.

__________

astounding knitting photos: estonia76

(Update below)

I write mostly about neuroscience, genetics and biotechnology. That means I spend most of my time talking to and writing about men.

In May of 2011 (chosen arbitrarily just because it was a year ago and I’m pretty sure I wasn’t thinking about this gender gap then), 89 percent of my phone interviews were with men.

I can think of a few reasons for this. One is that journalists typically talk to the senior leaders of labs, rather than the graduate students or postdocs who actually do the work. As you climb higher up the ladder of academic science, the male-to-female bias grows. According to the latest stats from the National Science Foundation, women earn 57 percent of all science and engineering undergraduate degrees and 41.1 percent of doctoral degrees. Yet the number of male PhDs in science jobs outnumbers females by two and a half times.

Another possible reason: Within science, the subfields with the most female-friendly sex ratios are: psychology (which employs twice as many women as men), political science (balanced ratio), and anthropology/sociology (balanced ratio). In contrast, for my pet topic, biology and life science, about twice as many jobs go to male versus female PhDs. Neuroscience, in particular, has a reputation for male domination. As of 2006, only 1 in 5 papers published in Nature Neuroscience — one of the field’s top journals — had a female corresponding author. A 2009 survey of neuroscience departments and programs reported that just 29 percent of tenure-track faculty are women. “So many of our best students and postdocs are women,” says Ben Barres, chair of neurobiology at Stanford. “But you don’t see them represented in our faculty. A lot of them are dropping out.”

Continue reading

My husband and I often take nighttime walks. On one such walk, I noticed something strange on the ground. It looked like a shiny stick. I leaned in for a closer look and realized I was looking at a long, fat worm. “Is this a worm?” I asked my husband. (I like to ask questions for which I already have an answer.) As he made his way over, I spotted more worms. The scruffy patch of dirt between the sidewalk and the curb was laced with them. “Oh God!” I yelped. “They’re everywhere. Look at them all!” I was shouting now. “Where did they come from!?”

My husband and I often take nighttime walks. On one such walk, I noticed something strange on the ground. It looked like a shiny stick. I leaned in for a closer look and realized I was looking at a long, fat worm. “Is this a worm?” I asked my husband. (I like to ask questions for which I already have an answer.) As he made his way over, I spotted more worms. The scruffy patch of dirt between the sidewalk and the curb was laced with them. “Oh God!” I yelped. “They’re everywhere. Look at them all!” I was shouting now. “Where did they come from!?”

My first thought was that someone had dumped their fishing bait. But as we circled the block, I noticed more worms. Hundreds of worms. This was no bait dump. The entire worm community seemed to be above ground. I couldn’t see well, so I ran into the house to get a headlamp. And, yes, there they were, dozens upon dozens of long pink bodies, all groping the ground with their pointy heads.

In one spot, I found two worms that seemed to be attached. These worms lay perfectly still. This could only be one thing. Sex. Worm orgy. And I had front row seats.

I ran back inside. My husband was watching TV. “Sex!” I screamed. “They’re having sex.” I was sure of it. But just to be double sure, I googled. Up came dozens of pictures of worms fornicating. They looked exactly like the worms in my front yard. I was elated. I felt like Christopher Flipping Columbus setting foot on the shores of an unknown continent. Except the continent was my front yard. And instead of people, I found worms. Continue reading

Abstruse Goose’s little mouseover says, Please credit the original artist. And he’s right, it’s nice to look at the world as though it’s art. You can’t help but notice the original artist had great taste in color and in which colors to put together. Like, the night sky is the original setting for diamonds against black velvet. You all must have your own examples.

Abstruse Goose’s little mouseover says, Please credit the original artist. And he’s right, it’s nice to look at the world as though it’s art. You can’t help but notice the original artist had great taste in color and in which colors to put together. Like, the night sky is the original setting for diamonds against black velvet. You all must have your own examples.

Except my neighbor, Al, who told me in a voice full of evil mischief that those neon red and violent magenta azaleas that he planted next to each other were beautiful because all the colors of nature went together. I forebore to say that not one of those colors was one God had ever seen before.

Ever since I reviewed Ignorance: How it Drives Science, a charming new book by the Columbia neuroscientist Stuart Firestein, I’ve been thinking about ignorance. And I tell you, it’s been a bit of a headache.

Ever since I reviewed Ignorance: How it Drives Science, a charming new book by the Columbia neuroscientist Stuart Firestein, I’ve been thinking about ignorance. And I tell you, it’s been a bit of a headache.

Firestein teaches a popular science class at Columbia, also called Ignorance, in which he invites scientists from different disciplines to talk about what they don’t know. (“Recruiting my fellow scientists to do this is always a little tricky — ‘Hello, Albert, I’m running a course on ignorance and I think you’d be perfect,’” Firestein writes.) But Firestein’s guests soon realize that they, like all scientists, are in the business of creating questions — of creating ignorance, so to speak. “Once they get over not having any slides prepared for a talk on ignorance, it turns into a surprising and satisfying adventure,” Firestein says.

Of course, the scientific pursuit of ignorance has long been exploited by those with something to lose from it. The tobacco industry perfected the strategy: Portray the doubt and uncertainty inherent in science as, well, plain old doubt and uncertainty — otherwise known as very good reasons not to act.

This week was LWON’s second birthday. To celebrate, we rounded up some of our favorite comments of the past year and threw them a little party.

Cameron told us why abalone are like Neil Gaiman, just putting his ideas out there, never knowing what would be read, what someone might respond to.

Funny enough, that’s also what Christie loves about unpaid blogging; no paycheck means no “producing content”.

Christie also tells us what it was like to watch the annular eclipse through wine-in-a-box, and the importance of thinking about your place in the universe.

Some people have Bette Davis eyes; Cassie explains to us about her “mushroom eyes.”

See you next week!

Single White Abalone: female, 7, seeks male. Too bad we’re not hermaphroditic like terrestrial gastropods, or I wouldn’t have to be so picky. Likes: rocky substrate, algae. Looking for a mate who lives within three to five meters. Long-distance just doesn’t work for me.

The white abalone, the first marine invertebrate to make the federal endangered species list, has a problem with distance. In fact, most abalone do. They’re broadcast spawners, sending their gametes out into the sea. If a male and female are farther than five meters apart, it’s like they’re on opposite sides of the ocean—they won’t be able to reproduce.

So when something starts to wipe out their population—overfishing, diseases, predators like sea otters—things can go bad, and quickly. Continue reading