So what do we do about invasive species? Exterminate ’em, right? and feel holy about it. And when the invasives are goats on the Galapagos, we still exterminate ’em, right? Only it doesn’t feel so holy, says Virginia.

Ann, in her obsessive search for the metaphors of science, finds another one: sub-grid physics, or making it up as you go but not fooling yourself about it.

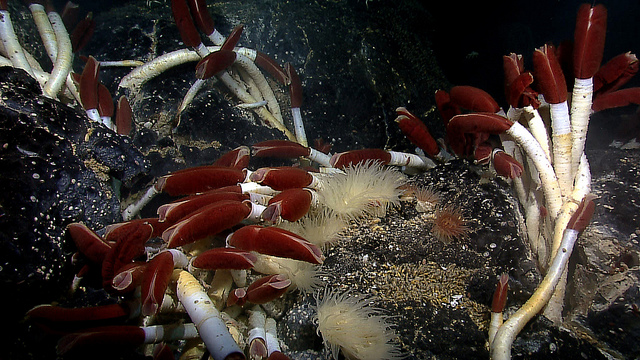

Guest Erin Gettler loves the old naturalists who observed so closely for so many years so she tries it herself, gets bored, thinks she’s doing something wrong, tries again.

The Colorado River water crisis, says Michelle, might be solved “if water negotiators in the western United States can bring themselves to act like giant tubeworms — even a little bit.”

Richard reads through his inbox the morning after the announcement of the Higgs boson, is on the whole happy, but don’t get him started on “God particle. And while you’re at it, look at the picture of those people listening to the announcement — have you ever seen a bunch of backs look more intense?

Bonus: the Galapagos/Judas goat post has a lively comments fight.

——–

photo by Erin Gettler