This post is a re-run from 7/15/2010. The situation hasn’t improved.

I grew up noticing what a writer notices — stories and how things are said — and educated myself accordingly. So I never learned much science and now, after I’ve unexpectedly turned into a science writer, my questions to scientists are generally English-major questions.

Me: Why do a tennis ball and a bowling ball fall at the same speed?

Physicist: Are all your questions like this?

My problem is made worse because I write about the physical sciences which, with the exception of gravity, are rarely part of an English major’s life experience. Nevertheless, on the whole, scientists are tolerant of my questions. Maybe they understand the unfathomable distances between their education and mine. Maybe because they usually teach undergraduates, they are used to such questions. Or maybe they don’t expect much from me in the first place: like the dog walking on its hind legs, they think, the wonder is not that she does it well but that she does it at all.

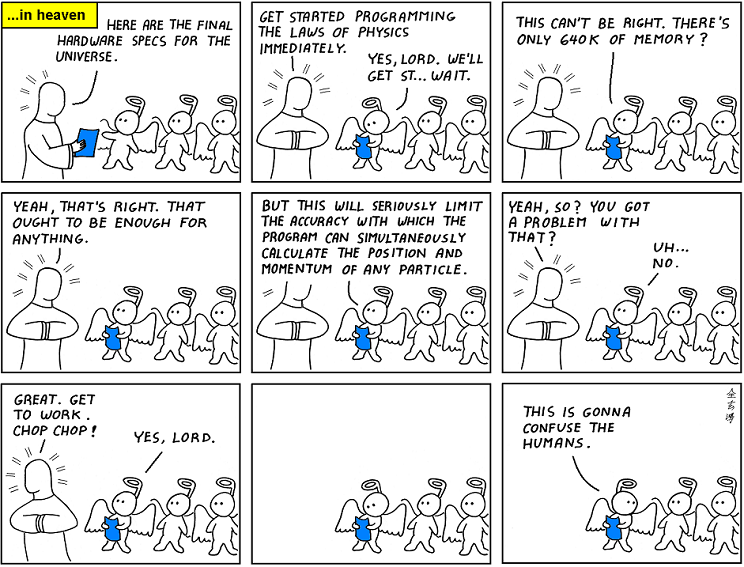

As I ask my questions, I can see them trying to figure out how to answer, how to communicate with this creature from another world, how translate the equations in their heads into words, let alone words about relationships between abstracts. They’re earnestly trying their best to communicate but sometimes they get tired and give up.

Me: Can you explain to me the work you did in quantum field theory?

Physicist: You asked me that the other day and you couldn’t understand what I told you then. That would still be true. Continue reading