For nearly five decades, a scientific loner guarded a great labyrinth of lines on the desert floor near the small Peruvian town of Nazca. Day after day, until she was too elderly and too ill for such solitary work, Maria Reiche set out into the barren vastness with camera, compass, and papers, mapping thousands of straight lines and dozens of immense ground drawings inscribed on the desert floor more than 1500 years ago by the Nazca, masters of maize agriculture and irrigation.

For nearly five decades, a scientific loner guarded a great labyrinth of lines on the desert floor near the small Peruvian town of Nazca. Day after day, until she was too elderly and too ill for such solitary work, Maria Reiche set out into the barren vastness with camera, compass, and papers, mapping thousands of straight lines and dozens of immense ground drawings inscribed on the desert floor more than 1500 years ago by the Nazca, masters of maize agriculture and irrigation.

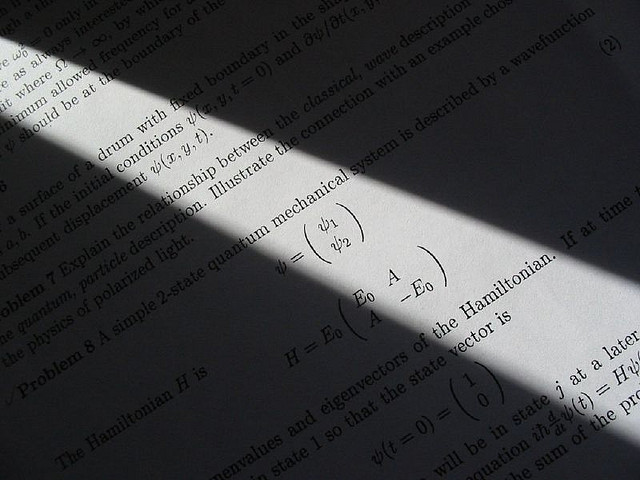

Reiche had studied mathematics as a young university student in Weimar Germany. She thought that the Nazca Lines formed a vast celestial calendar, an early scientific masterpiece akin to the calendar that Maya astronomers created and preserved in bark-paper books known as codices. Reiche believed the desert was a Nazca codex, and she brooked no intruders, no vandals on the lines. She paid for guards herself, and by the strength of her convictions she persuaded the Peruvian government to protect the lines. After her death in 1998, Alberto Fujimori, then president of Peru, talked of renaming them the Reiche Lines.

I was reminded of all this, when I came across a Reuters news story from Lima last week. Continue reading