But not every day is a good day. For good journalism, you will have entire days wasted on logistics, getting lost, or just plain sitting on your butt. That’s kind of what happened a couple weeks ago.

During the war, German anatomists who were university professors did research on bodies of people who died in the concentration camps. I don’t know how Heather can even write about it.

Guest Jill U. Adams talks to her son about driving rules and speed limits, has to figure out what to tell him about life’s gray areas. The Northeast’s fish restoration efforts aren’t helping.

A reality show that Jessa actually learned from: indigenous arctic people raised in the cities, sent back out on to the tundra. Turns out they don’t know how to tan moosehide.

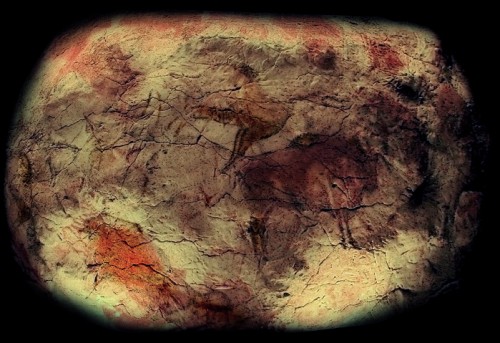

Guest Michael Balter goes to an ice age exhibit at the British Museum called Arrival of the Modern Mind. He loves it He wishes that its judgment of modern wasn’t off by 100,000 years.

Erika decides the apple juice has been in the frig long enough, decides she better drink it, asks Tom what’s the weird stuff floating in it, Tom’s no help. Dear reader, should she drink it or not? HELP!

When the British Museum puts together an exhibition of more than 100 pieces of prehistoric art from all over Europe, stretching back nearly 40,000 years, you want to go. And so I did, making the rounds of this spectacular show the day after its opening on February 7. You’ve got until May 26 to see it yourself, and it’s as good an excuse as any to visit London and maybe even catch a glimpse of William and Kate while you’re there.

But I had mixed feelings about the exhibition, not least because of its title: “Ice Age art: Arrival of the modern mind.” What does this mean? Was the human mind already modern on its arrival in Europe, or did it only get modern after its arrival on the continent, borne by anatomically modern Homo sapiens immigrating from Africa? Indeed, the title immediately evoked what most human origins researchers today would consider a retrograde, Eurocentric view of human evolution.

I have to admit, that very first episode of Survivor, oh so many years ago, held a certain wow factor for me. I was amazed they were allowed to do such a thing, back when it appeared as if they were truly going to leave a group of people to their own devices on a desert island. But as the voting procedures and lame challenges proliferated, all appeal quickly faded, and I’ve never enjoyed another episode of reality television. Until now.

In the deep recesses of the Aboriginal People’s Television Network website, a new series from my neck of the woods (Arctic Canada) is streaming its episodes in full. Dene: A Journey brings out the best a reality show has to offer. Each week features a young indigenous adult who lives an urban lifestyle, disconnected from their traditional culture. They are sent out on the land with elders to learn particular skills they’ve always meant to pick up but somehow never had the chance to experience. Continue reading

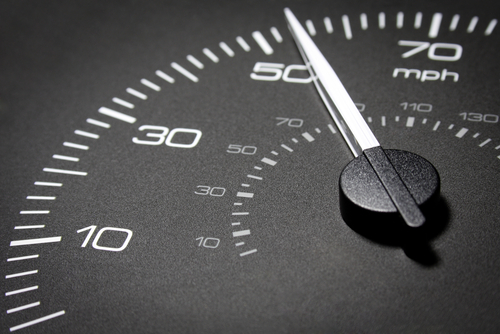

My 16-year-old son has started to drive. He holds a learner’s permit, which means he can’t drive without me sitting in the passenger seat. Me, narrating, reminding, commenting, coaching, evaluating, and reinforcing. We haven’t done much highway driving yet, so I haven’t directly addressed the idea of breaking the law — which almost everybody on the highway does.

My 16-year-old son has started to drive. He holds a learner’s permit, which means he can’t drive without me sitting in the passenger seat. Me, narrating, reminding, commenting, coaching, evaluating, and reinforcing. We haven’t done much highway driving yet, so I haven’t directly addressed the idea of breaking the law — which almost everybody on the highway does.

Around town, he’ll ask me: “What’s the speed limit here?” I’ll say, “Probably 30 mph” or 40 or 25 or whatever the size of the road seems to allow. (And yes, I take pride in the fact that I usually guess right. I’m glad I can still be an expert at something for my almost grown son.) Yesterday, he slowed way down when he realized he was driving in a school zone. I said nothing, as if it’s a given that he’d follow the letter of the law.

But what about the highway? Will I say, “The speed limit is 55 mph here, but most people drive 60-65.” How will I frame that gray area between stated rule and common practice for my son? As a cringe-worthy “everybody does it” excuse or as a rationalization, based on what I believe to be true — that it’s safest to drive at the speed of others around you.

While we’re exploring gray areas, my son, let me point out that there are plenty of examples of rules and regulations put in place with the best intentions and then blithely ignored. Continue reading

In the first week of September 1942, 29-year-old Libertas Schultze-Boysen waited desperately for word of her husband Harro, an official in the Reich Aviation Ministry in Berlin. The couple had passionately espoused a cause that few Germans of the age dared even to discuss. With a small group of friends, Libertas and Harro organized a resistance group known as the Red Orchestra, and in 1941 Harro passed intelligence to a Soviet embassy official concerning Hitler’s plans to invade the Soviet Union—information that the Soviets sadly failed to act upon, at great cost to human life.

In the first week of September 1942, 29-year-old Libertas Schultze-Boysen waited desperately for word of her husband Harro, an official in the Reich Aviation Ministry in Berlin. The couple had passionately espoused a cause that few Germans of the age dared even to discuss. With a small group of friends, Libertas and Harro organized a resistance group known as the Red Orchestra, and in 1941 Harro passed intelligence to a Soviet embassy official concerning Hitler’s plans to invade the Soviet Union—information that the Soviets sadly failed to act upon, at great cost to human life.

Libertas was the daughter of one of Berlin’s most famous couturiers, Otto Ludwig Haas-Heye, who also served as the head of the Arts and Crafts School in Berlin. She grew up in a world of beauty and elegance, far from the horrors that the Nazi regime began to visit upon its Jewish citizens and upon all political opponents. But the young German activist felt a deep need to do something about it. Continue reading

This week, Erik had a fascinating look at the people who think wind turbines are making them ill.

Cameron explained why alligators never have to worry about shrinkage.

Abstruse Goose neatly captured the infinite regress that tortures us science writers.

I told you how gross bugs do Valentine’s day.

And Richard investigated why the human brain treats time like a Slinky.

See you next week.