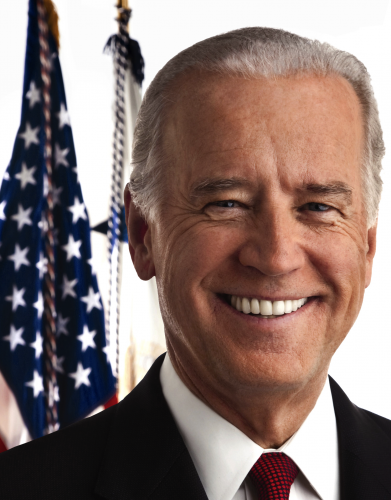

Kepler strikes again! A couple of weeks ago, in a two–part essay, I wrote about a 1608 book by the German astronomer Johannes Kepler that scholars consider the first work of science fiction: Somnium—Latin for The Dream. This past week, I got to thinking about Kepler’s book again, after the discovery of dwarf planet 2012 VP113 (which the discoverers have nicknamed VP, as well as Biden, because of all the stars in the background of his official portrait) (or maybe not), an object that redefines the edge of the solar system.

Kepler strikes again! A couple of weeks ago, in a two–part essay, I wrote about a 1608 book by the German astronomer Johannes Kepler that scholars consider the first work of science fiction: Somnium—Latin for The Dream. This past week, I got to thinking about Kepler’s book again, after the discovery of dwarf planet 2012 VP113 (which the discoverers have nicknamed VP, as well as Biden, because of all the stars in the background of his official portrait) (or maybe not), an object that redefines the edge of the solar system.

In Kepler’s book, a narrator recounts a dream in which he reads a book about a boy who hears a story from an alien who often travels to the Moon. Kepler had good reason to keep his distance, authorially speaking. To imagine the universe from a perspective other than Earth’s was a radical notion—so radical that The Dream wasn’t published until 1634, four years after Kepler’s death.

I don’t think the discovery of a dwarf planet—or the idea of there even being such a thing as a dwarf planet—would have surprised Kepler. In The Dream, he’s open to exotic possibilities. The alien describes enormous creatures with spongy skin that turns brittle in the sun. Instead, I think if you told Kepler that a planet-like object would be discovered at the edge of the solar system, his response would have been pleasure at the use of the term “solar system”: The system really is solar, as in, you know, revolving around the Sun? (Okay, the “you know” might be anachronistic.)

March 17 – 21

March 17 – 21