As I’ve followed the NCAA basketball tournament (join me and some folks from Radiolab tonight, as we live tweet the final game), I’ve been thinking about the value of collegiate sports. My first experience with sports in college came as an NCAA division I cross-country runner. I lettered in cross-country at the University of Colorado my freshman year, but a freak knee injury cut short my collegiate running career. Though I had no experience in the sport, I started training with my school’s Nordic ski team, and I also bought a bike and joined the cycling team.

As I’ve followed the NCAA basketball tournament (join me and some folks from Radiolab tonight, as we live tweet the final game), I’ve been thinking about the value of collegiate sports. My first experience with sports in college came as an NCAA division I cross-country runner. I lettered in cross-country at the University of Colorado my freshman year, but a freak knee injury cut short my collegiate running career. Though I had no experience in the sport, I started training with my school’s Nordic ski team, and I also bought a bike and joined the cycling team.

Cross-country and skiing were both division I, NCAA sports, but cycling was governed by its own body, outside of the NCAA system, and was overseen by club sports, rather than CU’s varsity athletic program. The difference was immediately noticeable. As a varsity NCAA athlete, I received special treatment — advance, preferential registration for classes, private tutoring if I needed it, and excused time from class to attend practice and meets, not to mention free tickets to all sporting events. This special treatment fostered a sense of privilege. We were part of the student body, but we were treated as if we were somehow above it.

My teammates and I were good students, and we were there to get a degree, we didn’t expect to make a profession out of sport. Nevertheless, as varsity athletes, we understood that performance was expected of us. Our sport was no hobby — we were there to win.

Things were different on the cycling team. Continue reading

Oh, but I was proud of myself yesterday. The rain was coming,

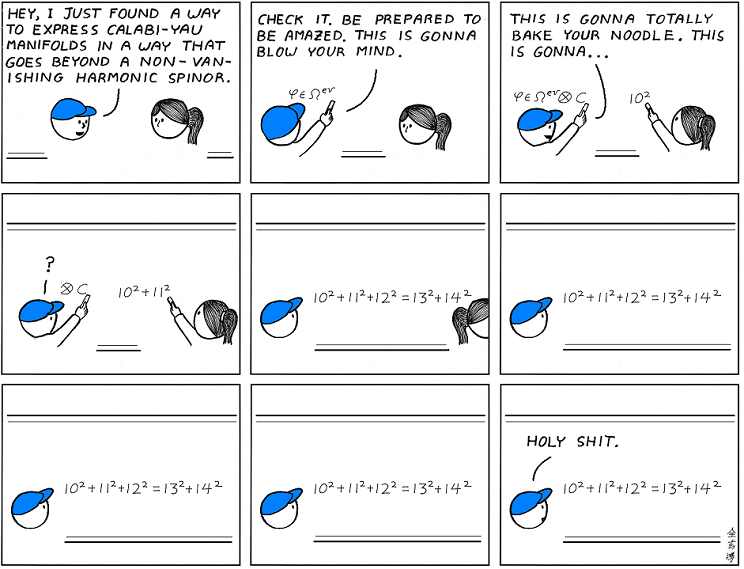

Oh, but I was proud of myself yesterday. The rain was coming,  April is Mathematics Awareness Month. April is also National Poetry Month. Coincidence? Yep, almost definitely. But it’s also an opportunity: I’d like to propose that we—you and I, at least until the end of this blog post—merge the two and celebrate the first-ever Mathematical Poetry Month. No fooling.

April is Mathematics Awareness Month. April is also National Poetry Month. Coincidence? Yep, almost definitely. But it’s also an opportunity: I’d like to propose that we—you and I, at least until the end of this blog post—merge the two and celebrate the first-ever Mathematical Poetry Month. No fooling. Kepler strikes again! A couple of weeks ago, in a

Kepler strikes again! A couple of weeks ago, in a