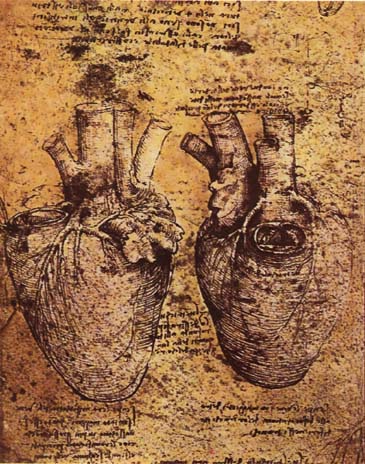

In his third post, Colin Norman faces a daunting prospect: heart surgery. “The operation isn’t as simple as snipping out the piece of aorta that includes the aneurysm and sewing in the Dacron tube. Because my aneurysm is right at the root of the aorta, the surgery would involve the left ventricle itself.”

Richard Panek treats us to more bad science poetry. Here’s my favorite line: “The Higgs is a boson, not something with clothes on.”

Karen Masterson explores the US’s history of ham-handed attempts to “help” Liberia, and wonders whether the effort to get the ebola outbreak under control will be the latest example. “Don’t step in again with a big foot and then leave. There’s no pill to make Ebola go away; it will come back.”

Helen Fields catalogues all the times that she has been pooped on by birds in the past decade. The list is extensive. “An informal poll of Facebook friends finds that I have been pooped on more in the last decade than everyone but a dog walker and a biologist.”

And on Friday, Ann Finkbeiner calls on Geoff Brumfiel and Sharon Weinberger to discuss Lockheed Martin’s announcement that the company is a decade away from having a fusion reactor. Geoff and Sharon are skeptical. “Couldn’t you just assert that you, Ann Finkbeiner, are going to build a fusion reactor ‘within 10 years.’ That’s what everyone else does,” Sharon says. Ann agrees to try.

Photos: “Fusion Reactor” by Annabeth Robinson, via Flickr