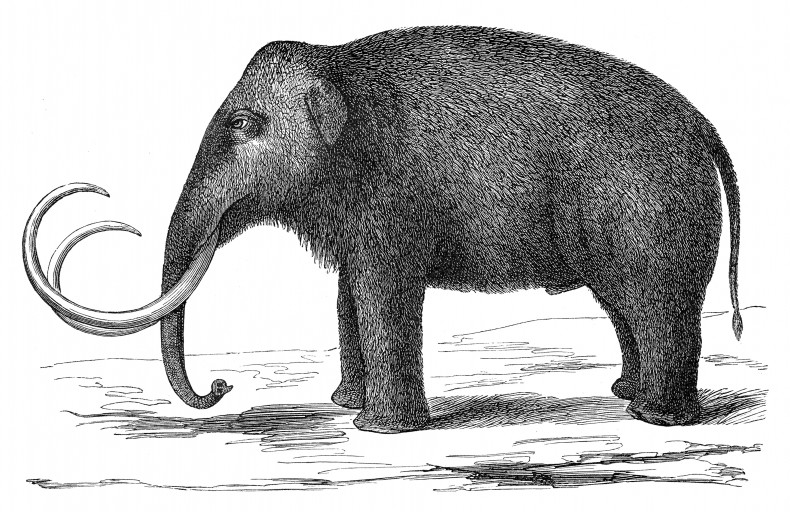

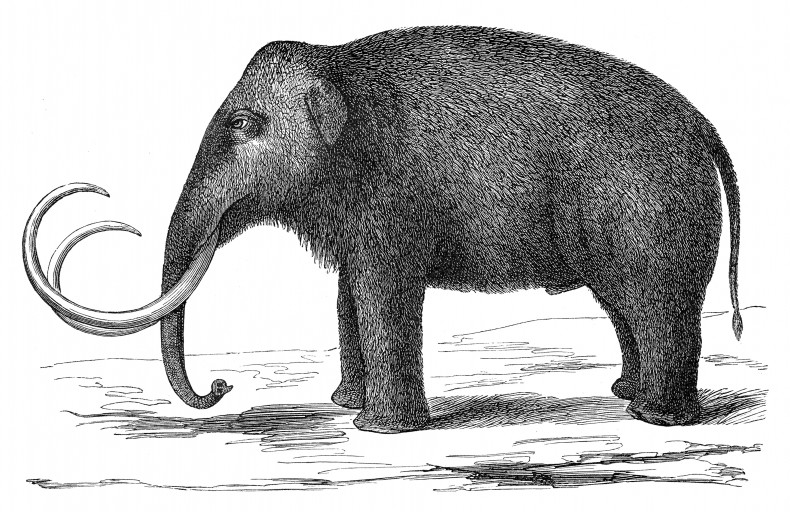

Seeing a mammoth is not the same as looking over a zoo wall at a modern elephant, or even standing next to a live, gray, wrinkled wall of flesh with scant, coarse hairs. Watching the flexible, prehensile reach of an elephant’s trunk and the slow cross-wise chewing of hay, I’ve found it hard to see the larger mammoth inside.

Seeing a mammoth is not the same as looking over a zoo wall at a modern elephant, or even standing next to a live, gray, wrinkled wall of flesh with scant, coarse hairs. Watching the flexible, prehensile reach of an elephant’s trunk and the slow cross-wise chewing of hay, I’ve found it hard to see the larger mammoth inside.

Elephants and mammoths are obviously related, both proboscideans evolved from a trunked African animal the size of a pig some 60 million years ago, eventually becoming the largest land animal on earth. The earliest version of the mammoth, Mammuthus subplanifrons, originated in the African tropics about 5 million years ago. A later mammoth, Mammuthus meridionalis, entered forests and grasslands in Europe and Asia about 3 million years ago, eventually leading to the famed wooly mammoth, Mammuthus primigenius, which adapted to cooler, more arid treeless conditions in the north from the British Isles to eastern Siberia and into North America. The wooly mammoth was a latecomer to the New World, arriving from Siberia across the land bridge only 100,000 years ago. A previous mammoth species had arrived in North America a million years earlier and moved into warmer more southerly parts of the continent where it evolved into the what is known as the Columbian mammoth, Mammuthus columbi. This was one of the larger proboscideans to have ever lived, up to 13 feet tall at the shoulder.

In museum collections, I’ve looked for this animal by running my hands along the arcs of their tusks, 10 or 12 feet of solid ivory, colored chestnut from time in the ground. In the clean lighting and gentle hum of air ducts, I still couldn’t see the actual beast. Taken out of the context of its environment, I saw paleontologists and plaster jackets more than I saw mammoths.

The best view I ever had of this animal was in the gypsum wastelands of a bombing range in southern New Mexico where mammoth tracks have been repeatedly discovered. Continue reading →

In the beginning: The week started with Part IV of guest Colin Norman’s every-Monday series on undergoing heart surgery. (Spoiler alert: He lives to write another day.)

In the beginning: The week started with Part IV of guest Colin Norman’s every-Monday series on undergoing heart surgery. (Spoiler alert: He lives to write another day.)