You may have heard that conservation biologists are arguing with each other. Some say nature should be protected for humans; others say it should be protected from humans; others say it’s possible to do both. This may sound like an academic debate—and in many ways it is—but it has become a very nasty one, and over the past couple of years it has severely taxed an important field that has far too few resources to begin with.

You may have heard that conservation biologists are arguing with each other. Some say nature should be protected for humans; others say it should be protected from humans; others say it’s possible to do both. This may sound like an academic debate—and in many ways it is—but it has become a very nasty one, and over the past couple of years it has severely taxed an important field that has far too few resources to begin with.

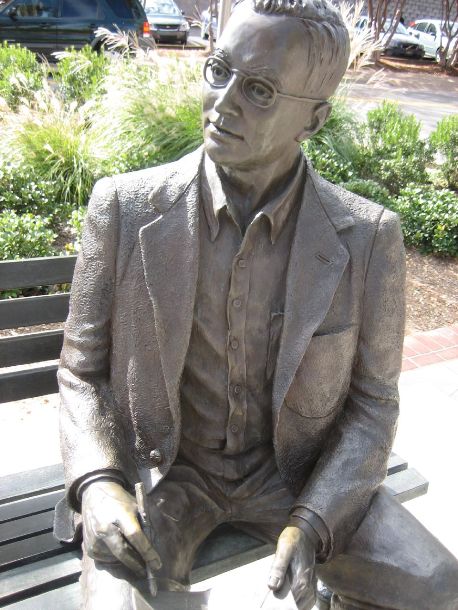

I’ve written about the argument’s gory details elsewhere, but here I’d like to take a longer view. For this fight was, in its broadest sense, settled more than a half-century ago, and the referee is still relevant. His name was Aldo Leopold. Continue reading

The other day while we were playing at a nearby park, a woman got out of her car and swooped over to where my sons and their friends were trying to flip over small boulders. She had these awesome knee high boots, and bright red lipstick. Seeing her reminded me what happens to everyman hero Emmet in The Lego Movie’s everyman when he first sees master-builder WyldStyle—the world goes fuzzy, and the screen is filled with her smile, her stiffly swooshing hair and an angel choir soundtrack.

The other day while we were playing at a nearby park, a woman got out of her car and swooped over to where my sons and their friends were trying to flip over small boulders. She had these awesome knee high boots, and bright red lipstick. Seeing her reminded me what happens to everyman hero Emmet in The Lego Movie’s everyman when he first sees master-builder WyldStyle—the world goes fuzzy, and the screen is filled with her smile, her stiffly swooshing hair and an angel choir soundtrack.