Exactly 10 years ago today, I got one of those calls we all dread. My mom had cancer, a stage-4 brain tumor, the kind that seems to pop up out of nowhere fully formed and beyond repair. I was standing in my kitchen when I heard the news, and I remember dropping the phone as I slid down the wall to the floor, unwilling to process what it meant. She lived just over two months after her diagnosis, and I spent most of that time helping to care for her. Not surprisingly, the holiday season, already crushingly stressful, has ever since been a melancholy time for me.

A few years after my mom’s death, I wrote an essay about her, called Her True Calling: My Mother’s Last Gift, that ran in the Washington Post Style section. I was amazed at the reception—it reached so many more people than I expected, and hundreds of them let me know how much it meant to them. I was moved by and grateful for all of their comments.

So, in honor of my mother, and in a bit of shock at the fact that a decade has passed without her, I’ve decided to run a slightly modified version of the original essay here on LWON. I hope it touches a new audience and reveals once again how special this woman was to me.

—

Her True Calling

My mother stopped trying to find herself when the tumor in her brain spilled from one hemisphere into the other, pushing the midline to one side like an unexpected bend in an arrow-straight road.

“They’re on the move,” she told me over the phone from the hospital the night she was diagnosed. “They’re marching through.” I suppose that in her drug-induced haze she meant the tumor cells were like soldiers advancing, leaving rubble in their path. It was the night before Thanksgiving, and after that she forgot where she was going.

For years she’d sought something she couldn’t explain. “I need to fill my cup,” she’d say. She tried it all: acting, singing, politics, religion, painting, buying houses and selling them soon after — a “hobby” that almost ended her second marriage. She was going to save the local theater, fight animal cruelty, help dying children get wishes granted. As a nurse she traipsed endless avenues — obstetrics, children’s cancer, ER, addiction, Hospice — and to each she brought a special compassion and gentle hand. And each time she switched directions she thought she’d find that thing she was supposed to do, the person she was supposed to be.

I can picture her pondering her next move, sitting in her favorite sunny room upstairs with the sink-down chair wide enough for curled knees and two cats, the dream catchers and Santa Fe talismans on the walls. Her shelves are heavy with books (on laughter, on forgetting) and trinkets — Dorothy’s ruby slipper in miniature, a dish of sand raked into soothing swirls, urns of ashes of past cats and our old Weimaraner Gretel. And she has pictures of me here and there, one from our mother-daughter trip to Mexico years back — a shot of two giddy brown-eyed brunettes sipping sour drinks through curly straws, our mouths in tight O’s — and of me posing with her in mind while on writing assignments around the world for National Geographic. She’d tell anyone who’d listen about me and my adventures, as proud a mother as I’ve ever known.

“Jenny, my love, my love,” she sang into the phone one afternoon. “I think I’ve finally figured out what I need to do.”

I braced myself, recalling recent talk about crystal energy therapy and angels with names like Bob and Sandra who were watching over her. (She later laughed at such a silly idea—everyday angels?—as if it hasn’t been hers.)

But she surprised me with something reasonable. She was going to be a hospital chaplain, she said, and she’d already spoken to a woman at the Clinic who could mentor her.

It was something I could imagine her doing well, and I wanted to be supportive. But this conversation was painfully familiar and I couldn’t give in so easily. I’d grown weary of the constant flip-flopping from dream to dream, a once-endearing trait that had begun to make me sad, especially as I’d seen similar torments in myself: indecision, dissatisfaction, the fear that what was out there was better than what was inside me. I snipped at her: What happened to starting a foundation? Running for mayor? Revamping the animal shelter?

She was never put off by my tone, never let the negativity in. Her new career choice made more sense, she said. Politics gets too ugly — all that testosterone. This is more spiritual and would fill that hole in her life.

But as always came the obstacles. The application asked for essays on who she was and what she believed. That meant focusing, having and sticking to a perspective on life and death. (I later saw the yellow pad with her lovely compact script — it always looked like writing that was practiced, as when a woman is changing her name and wants to see if it’s pretty on the page. She filled less than two sheets, a lot of words crossed off, the whole thing trailing off mid-thought. She soon abandoned the paperwork.)

And she’d need to go back to school. Did she really need all those classes to help people? she asked. “Honey, I’m not sure if I know how to study anymore!” Still, she signed up for the first course, bought books and pens, notebooks with red covers and clean, smooth pages. I don’t know that she ever attended a session.

And then, they told her she had to declare herself something. “I have to pick a religion,” she moaned.

I had to laugh. “What did you expect?” I asked. “It’s a religious position.”

She sighed, audibly. “I guess I was hoping I could just be whatever each patient needed me to be.”

She never became a chaplain. She also gave up on a mayoral run, on building a university, on singing lessons. Her search for purpose reached out like a sunburst in all directions, and each pursuit gave her a glimpse at happiness before fizzling out. Nothing was enough to warm her through, to keep her cup filled.

And then she got very, very sick, and the search hit a wall.

It was nearly two months after her diagnosis, and my mother was a brittle shell. I was there in Minnesota’s winter gloom, having said no to one of those assignments that months before would have made her gush. I wanted, needed, to take care of her as she always had patients or pets or me when I was hurting. My stepdad and I had decided it was most humane to give nature control—researching her disease had given us purpose for a time—so no chemo, no radiation. Mom was getting steroids, insulin, morphine now and then. More important were the most basic of things: blankets layered to keep her warm, chocolate pudding to make her eyebrows lift (our signal for yes), soft music of flutes and wolf howls. A lot of loving hugs.

One night when she could no longer walk, and could barely speak, we spent the evening sitting together in the quiet of her room. The China-red walls were covered in family photos my stepfather had hung — of my husband and me, my brother and his wife, their boy, the grandchild my mother wanted for years and now would never know. And it got to me — all of it. The horror of her decline, the humiliation she’d endured. The body and mind that had been stolen from her. After years of being a nurse to others, she could no longer put a spoon to her mouth or a brush to her hair. And she would fade away some night soon still unsure of who she was.

My stepfather lifted her, a rag doll, onto the portable toilet set up near her bed. Her pajamas were stained down the front with cottage cheese. Blankets trailed from her shoulders, towels lay on the floor from the last cleanup. Pride gone. Muscles gone. Her hair was thin and upended from sleeping and smelled of scalp; that lovely smooth skin had finally lost its youth. And her eyes were heartbreakingly sad; in recent days they’d hardly connected with us, with anything we could see.

I was sitting holding her skeletal hand when I finally broke. Crying aloud, letting it all out — feelings hidden from her for all those painful weeks. Suddenly a child who had seen too much, I wanted to crawl away and escape the scene, the smell of disinfectant, the trill of that damn flute music that will always, always sing of death to me. I cried knowing there was so much left in life for her to try — why hadn’t I, who quietly shared her vacillating nature, helped her to find what she craved?

And yet my mother, exposed and ready to die, suddenly looked right at me for the first time in weeks, through her stringy hair and straight into my eyes, and held and patted my hand. And she said, her voice gravelly but familiar for one beautiful moment, “It’s okay, Jenny. Sweet girl. Don’t be sad for me. It’s really okay.”

And just then it was clear to me, as perhaps it was to her: She was already playing the part that suited her perfectly — with no audition, no essay, no special declaration but love. Above all, even when intent on the journey to find herself, she had always made time to be a wonderful mother to me, never failing to wipe away my tears and ease my pain. It was the one role she could see through to the end.

—-

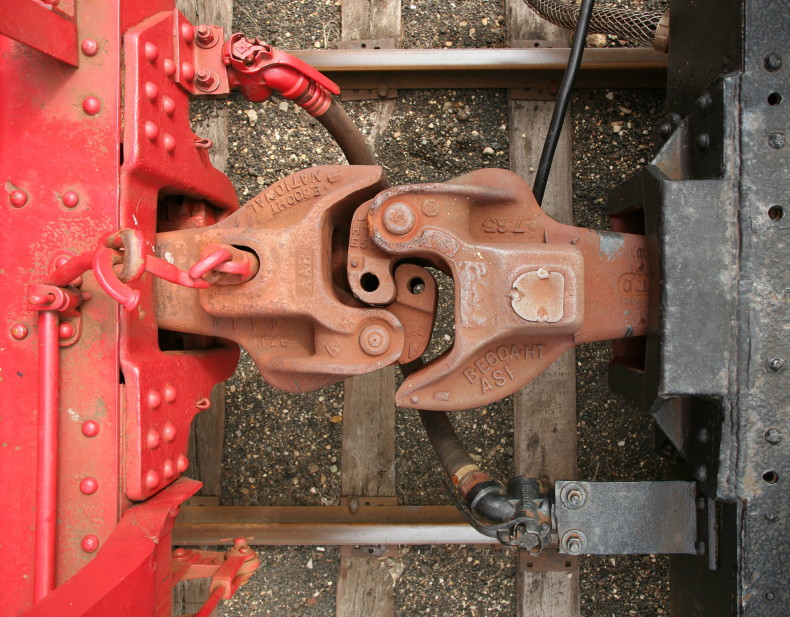

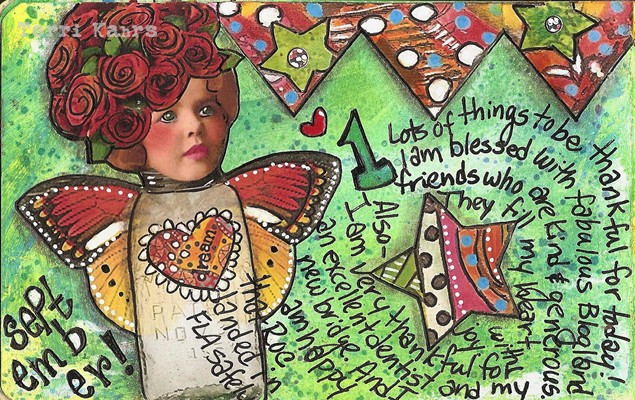

Photos: Mom doing her Santa Fe thing, in healthier times; Mom and me, toward the end.

Over the past six weeks, my sister and two of my dearest friends have celebrated landmark birthdays (the kind with a zero at the end). These festivities have left me thinking about birthdays. Why do we celebrate them?

Over the past six weeks, my sister and two of my dearest friends have celebrated landmark birthdays (the kind with a zero at the end). These festivities have left me thinking about birthdays. Why do we celebrate them?

I didn’t know how much I cared about pie until I realized I wouldn’t be having one this week. We’re going snow camping and although I know that it’s possible to make a pumpkin pie with a campfire, a little creativity and the right ingredients, at this point I just want to focus on making sure we have enough warm layers and hot chocolate to get us through the nights.

I didn’t know how much I cared about pie until I realized I wouldn’t be having one this week. We’re going snow camping and although I know that it’s possible to make a pumpkin pie with a campfire, a little creativity and the right ingredients, at this point I just want to focus on making sure we have enough warm layers and hot chocolate to get us through the nights.