Just recently, the Chinese government ended its one-child policy, telling married couples they could reuse their nurseries one more time. It wasn’t out of the goodness of officials’ hearts. The original policy, put into effect in the late 1970s, was about demographics, an attempt to control the pull on the flailing economy. The change is still about demographics. Eventually a child-limiting policy tips a populace toward the elderly, and the Communist Party is now ready to pump more young bodies into the system.

That a government can have any say over baby making is hard for many of us to swallow. It’s a true violation of the most personal of freedoms.

But Earth–or really, Homo sapiens—has a big problem. There are, at the moment of my writing this, 7,299,918,507 people sharing the planet, and those last digits are clicking up fast. [Watch it yourself.] China, India, and the little-old U.S. of A are the most prolific (the first two have whizzed past a billion each). A commonly cited estimate is that every second we humans have around four babies while only two of us die. Sounds like growth to me.

Growth isn’t spread evenly: In some countries it has slowed considerably, and worryingly for those governments. Parts of Europe are even seeing population shrinkage, as is Russia and Japan. But overall expansion continues: We are still projected to have a world population of 9.6 billion by 2050.

The U.S. government has been a big supporter of growth. After devastating losses from WWI and WWII, officials encouraged people to have more kids using tax incentives. Those haven’t gone away. Most U.S. parents today receive a $1,000-$3,000 credit on their federal tax return for each child dependent. Other countries have related incentives, whether straight-up money per kid (e.g., Australia) or, as in Germany, free childcare.

The economic model that many countries aim to follow, in fact, goes against logical science. Unlimited growth with limited resources is clearly unsustainable. Technology can only take us so far.

No one likes talking about overpopulation. It leads to often-ugly debates over what may be the most human thing we do. One can’t discuss making fewer babies without sounding elitist, racist, and many other “ists”…there are cultural, religious, and practical reasons some people have larger families than others. Those who suggest any of those reasons are outdated or selfish or bad for the planet are bound to feel the burn of a sizzling backlash.

Meanwhile, a federal government like ours is an animal that demands to be fed, by taxing the electorate and taking on massive debt based on the promise of repayment by generations to come. A country needs people to fill those coffers, to care for the elderly, to build roads and schools and banks, to spend their earnings and grow the economy. And maybe, robust populations of young people making a difference in the world are a source of national pride. No government wants its country to become a side note.

Can migration fill the void? In an ideal world, perhaps. Equitable distribution, open arms to those in need of a home, a neat blending of cultures that celebrates both differences and common ground…it sounds perfectly logical and moral. But wherever in the world I’ve been where diversity has become policy, I’ve seen it—discrimination, self segregation, battles over assimilation and representation. Distrust and all around bad behavior. Multiculturalism is a messy thing that, sadly, brings out all those ‘isms’ that divide us.

I’m no expert on population or on government policies related to demographics. I’ve simply been thinking about all this recently because I’ve been talking to scientists about panda conservation, for a Nat Geo article I’m writing. One source, Sarah Bexell of the University of Denver, took a step beyond the usual answer to “why are these animals in trouble.” Yes, it’s habitat destruction and lack of enforcement of reserve boundaries and the changing climate and the other usual suspects. But the core of the problem isn’t as much what we do as people as it is how many of us there are doing it. “Population growth the world over is at the root of all species declines,” she said.

Of course, she’s right. And this goes well beyond endangered species. Population is at the root of pollution, of poverty, of environmental degradation, of desertification, of food and water shortages. Name the issue and one could argue that with fewer people needing (and taking) resources, the problem would be manageable.

I’d be remiss not to note, though it’s obvious, how completely unbalanced that resource taking is around the globe. Our Western footprints are those of giants compared with so much of the larger world population. People in the West may be making fewer babies, but our outsize “needs” make us highly culpable in what’s happening to our environment.

I don’t know the answer to this Herculean problem, of course. If I did, I’d be getting all kinds of prizes. My husband and I don’t have children, and while overpopulation was on our minds as we made our decision, it wasn’t the main factor. Mostly, we just don’t like kids. (Just kidding. We like them. We just don’t want them touching our stuff.) We try to use resources wisely. But we use plenty of them.

I hate the idea of a government regulating family size. I would never argue for that route, here or in parts of the world that are growing fast. But incentives that go the other direction, that make small families, requiring less stuff, a good choice? Can a government support the truth that more of everything isn’t always best, and give credit to those who get behind that idea? It seems to me a better, more moral way to address the human problem, a shift more people can live with (though it would be political suicide for anyone in democratically elected office).

I know most adults feel a great pull to have children—it is, after all, what we’re built to do. I believe those people should be allowed to exercise their reproductive rights. And I know governments have economic reasons for growing the populace (which often don’t make real sense—a topic for another time, perhaps). It takes a bold leader to suggest that less is more.

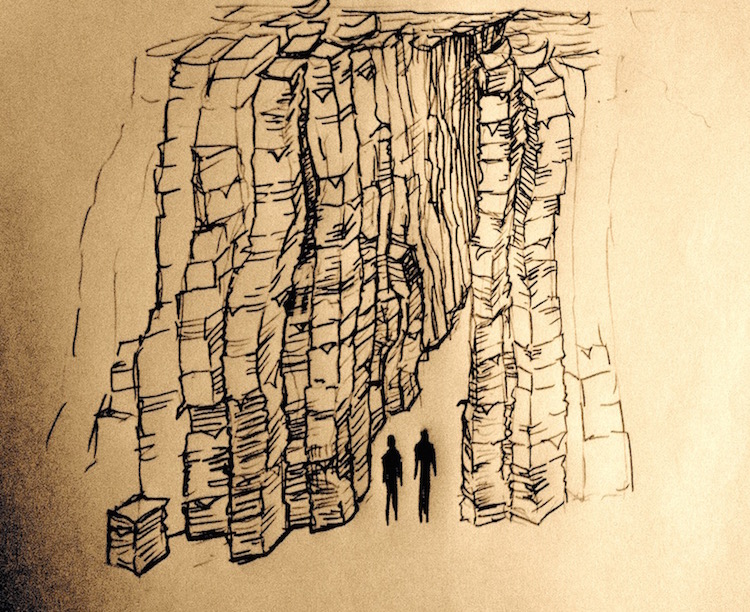

But when I step back to look at the global picture and trace the trajectory of our current path, I see excellent reasons for more of us to walk that path two by two.

Photos from Shutterstock

Yesterday: Urban Lichens, Part 1: OMG! Urban Lichens!, in which we learned that there are lichens in the city.

Yesterday: Urban Lichens, Part 1: OMG! Urban Lichens!, in which we learned that there are lichens in the city.