My kids are really into this cartoon called The Octonauts. It’s about a group of undersea rescuers and researchers (there’s a penguin medic, a sea otter marine biologist, a polar bear captain, among others, plus a group of squeaky-voiced creatures called vegimals.) In one of their (and my) favorite episodes, one of the crew members stays out all night to observe shy garden eels. Others wonder if he’ll be ok all alone out there, but the captain says it looks like it will be a quiet night: “Nothing out there but one little jellyfish. What could go wrong?” Continue reading

My kids are really into this cartoon called The Octonauts. It’s about a group of undersea rescuers and researchers (there’s a penguin medic, a sea otter marine biologist, a polar bear captain, among others, plus a group of squeaky-voiced creatures called vegimals.) In one of their (and my) favorite episodes, one of the crew members stays out all night to observe shy garden eels. Others wonder if he’ll be ok all alone out there, but the captain says it looks like it will be a quiet night: “Nothing out there but one little jellyfish. What could go wrong?” Continue reading

Early in the 17th century, two lions lived in the zoo in Ghent. Their names were Flandria and Brabantia. There were probably other lions nearby. Archduke Albert and his wife, Isabella, ruled the region, now in Belgium, and they had a menagerie at their palace. Having a menagerie was the sort of thing extremely wealthy people went in for at the time.

One way or another, the artist Peter Paul Rubens found his way to some live lions, put chalk to paper, and created images. The lions he drew are expressive and realistic, with manes and teeth. (Read more about them in this book.)

Rubens was a very influential painter, with a busy studio in Antwerp, and his lion drawings survived. The British Museum has a couple, and one (above) is here in Washington, D.C., in the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Art. It hasn’t been on display since a temporary exhibit in 1998, but you can make an appointment to visit it.

You don’t have to make an appointment to visit the final work that these lions ended up in, though. It’s Daniel in the Lions’ Den, a massive painting that hangs on the dark-paneled wall of Gallery 45, in the museum’s West Building. Continue reading

Being human is hard. Sometimes we treat each other poorly, putting our own feelings or wellbeing first. Mathematical-game models explain the logic behind selfish acts, suggesting that they often make the best sense. (Remember the Prisoners’ Dilemma?)

Being human is hard. Sometimes we treat each other poorly, putting our own feelings or wellbeing first. Mathematical-game models explain the logic behind selfish acts, suggesting that they often make the best sense. (Remember the Prisoners’ Dilemma?)

But straight-up logic dismisses empathy. The truth is that deep down, and sometimes even up near the surface, we’re actually quite good. Intuitively, we’re generous and cooperative. When given the choice to share and to trust that others will do the same, even if a selfish move promises a better individual outcome, most of us lean toward collaboration and shared gain.

Being kind can be catching. Hearing about a Good Samaritan’s good behavior, for example, may encourage us to do something nice, too. I know I’ve felt that way. As others make positive gestures around me, I often think, What have I done lately that’s not utterly about me? I like to think I’m a giving person, but when I break down my day-to-day actions, I’m sadly lacking in charity.

Friend and writing colleague Ann Finkbeiner recently posted a beautiful essay about how meaningful her friends’ and neighbors’ little generosities were as she mourned her husband’s death. I was part of a group who sent Ann a wool blanket as a gift we hoped would soothe her. She wrote to us when it arrived to say she loved it, that it was the perfect thing to help ease the kind of pain she was feeling. I felt warm inside reading her note, and good about myself for participating—reminding me that even kindness can have a selfish motive. Regardless, that ability to empathize and offer comfort is one capability we humans can be proud of. Continue reading

This interview with Radiolab’s senior editor (also my husband) focuses on why the show hasn’t done a story on climate change. It originally ran on May 22, 2014. Since then, Radiolab host Jad Abumrad has spoken the words “climate change” on air . . . as part of an episode on nihilism. Progress? (The show is actually one of my very favorites. You should listen.)

The most recent report from the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) doesn’t pull any punches. The globe continues to warm, ice continues to melt at an alarming pace, and the seas continue to rise. Climate change isn’t some distant dilemma. It’s already happening. The science is solid, and the problem is urgent. “Nobody on this planet is going to be untouched by the impacts of climate change,” said IPCC chairman Rajendra Pachauri at a news conference in March. Continue reading

February 15-19, 2016

Sea glass: a reworked human product returned to the sand from whence it was wrought. There’s less of it now, but you can tell a lot about its origins if you know what to look for.

Designer and writer Matt Steel is working on a simplified version of Thoreau’s Walden, and Michelle supports the experiment.

Ann’s husband died last month, and the empathy she received was an elixir that gave her pain meaning.

It’s disappointing when you’re onto a great story and a new source tells you why it’s not a story at all. Rose argues the lesson to take is to seek out those killjoys on every assignment.

The Arctic Circle is a group that has met monthly for 70 years. I attend for a talk about mercury.

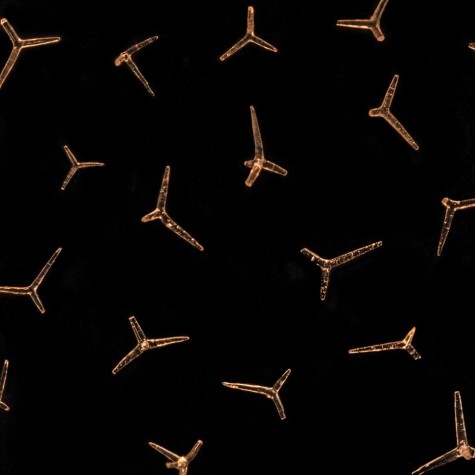

Image: Grains of sand from Ireland, candlelit, arranged with an acupuncture needle Jenny Natusch, www.sandgazer.com

On a slushy Ottawa night last week, I tromped into the Officer’s Mess of the Royal Canadian Air Force, here to attend the 513th meeting of the Arctic Circle. When I moved north to Yellowknife ten years ago, my Aunt Diana wrote that her husband Graham would have been pleased I was living in the land he loved so well. He had been an Arctic explorer, as they called northern geographical and archaeological activities in those days. Diana said she had a group of friends who met every month to discuss the Arctic, and she encouraged me to attend if I had the chance.

It turns out her monthly meeting has been taking place since 1947 – almost 70 years! – and features speakers from every discipline relevant to the region. Around 30 people were ranged behind heavy wooden tables and the lecturer, Alexandra Steffen, was here to induct us into the secrets of quicksilver – specifically the methylated form of mercury that causes havoc in growing human brains after bioaccumulating in the marine food chain. Continue reading

Last year, I abandoned a story. It happens, journalists don’t write every story they think they might. But this one I still think about.

It started innocuously enough. A paper caught my eye about looting and archaeology. The premise was somewhat counterintuitive: the author argued that in places where the economic situation was particularly dire, looters were looting because they had no other way to make money. I started reading other papers on looting and ethics. His cut against a lot of the arguments, and it appealed to my upper middle class liberal sensibilities. How dare we, in the West, sip our Starbucks and pass judgement on what people should and should not do with their own heritage, when they have nothing else to live on?

I talked to the author of the paper over Skype chat. He was nice and clear and convincing. It was a good conversation. Everything was going well. Continue reading

My husband died. He wasn’t young any more and was sick and weak but we weren’t expecting his death to come as quickly as it did, within a few days, almost overnight. He just went away. Maybe there are worse things than a quick, quiet death.

My husband died. He wasn’t young any more and was sick and weak but we weren’t expecting his death to come as quickly as it did, within a few days, almost overnight. He just went away. Maybe there are worse things than a quick, quiet death.

Here’s what happened next.

My brother and sister-in-law (who live a couple of hours away) called: We’ll be there tonight, and we’re staying until you make us leave.

A friend: I have some lentil soup, may I bring it over? And may I bring the rest of my family and we’ll all eat it together?

A neighbor: When you need to start sorting through things, may I help?

A friend: The kids and I are coming to Baltimore for the weekend. May I bring them and some pies, and come sit by the fire?

Empathy. Continue reading