I’ve been working on a couple of essays over the last week, knowing I had to fill this space. But when the time came to post one of them, I couldn’t do it. The subject was too irrelevant, too glib in the shadow of yet another sick fuck shooting innocent people. It didn’t belong.

This is not the first time I’ve paused before posting my work, even when I felt extra good about the piece I’d written. Occasionally there’s a collective change in tone that makes the text feel out of place in any public forum. When readers’ attention has been yanked in a single direction, it’s hard to lure them back—and under tragic circumstances it feels wrong to try.

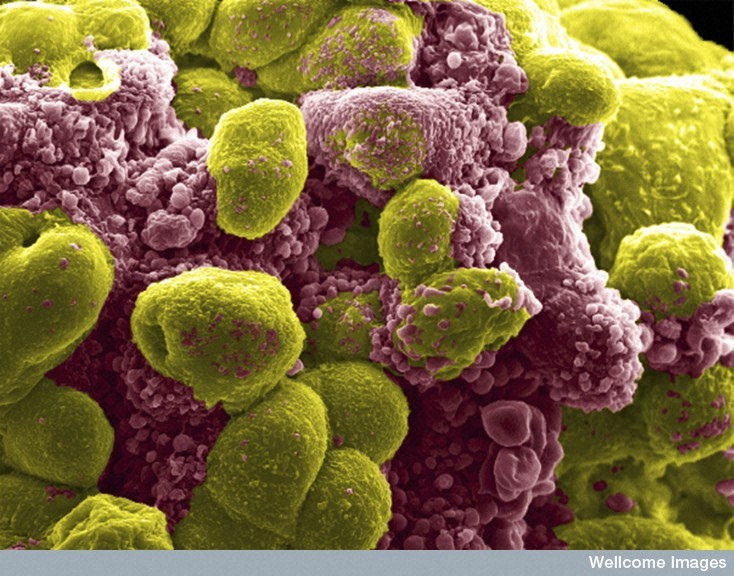

I’d imagine that most writers who publish on the Web have experienced this awkward mental flip-flop, questioning the validity and timing of their work before hitting “post.” As one who often covers quirky animal science or, here on LWON, personal absurdities from colonoscopies to battles with beach fleas, I’ve finally named the feeling because it has become so familiar. I call it J-Shame (for Journalists’ Shame). It hits when your beat is way out of synch with a big tragic thing that’s on everyone’s mind. It shrivels your confidence and embarrasses you for not taking on something with bigger-picture importance.

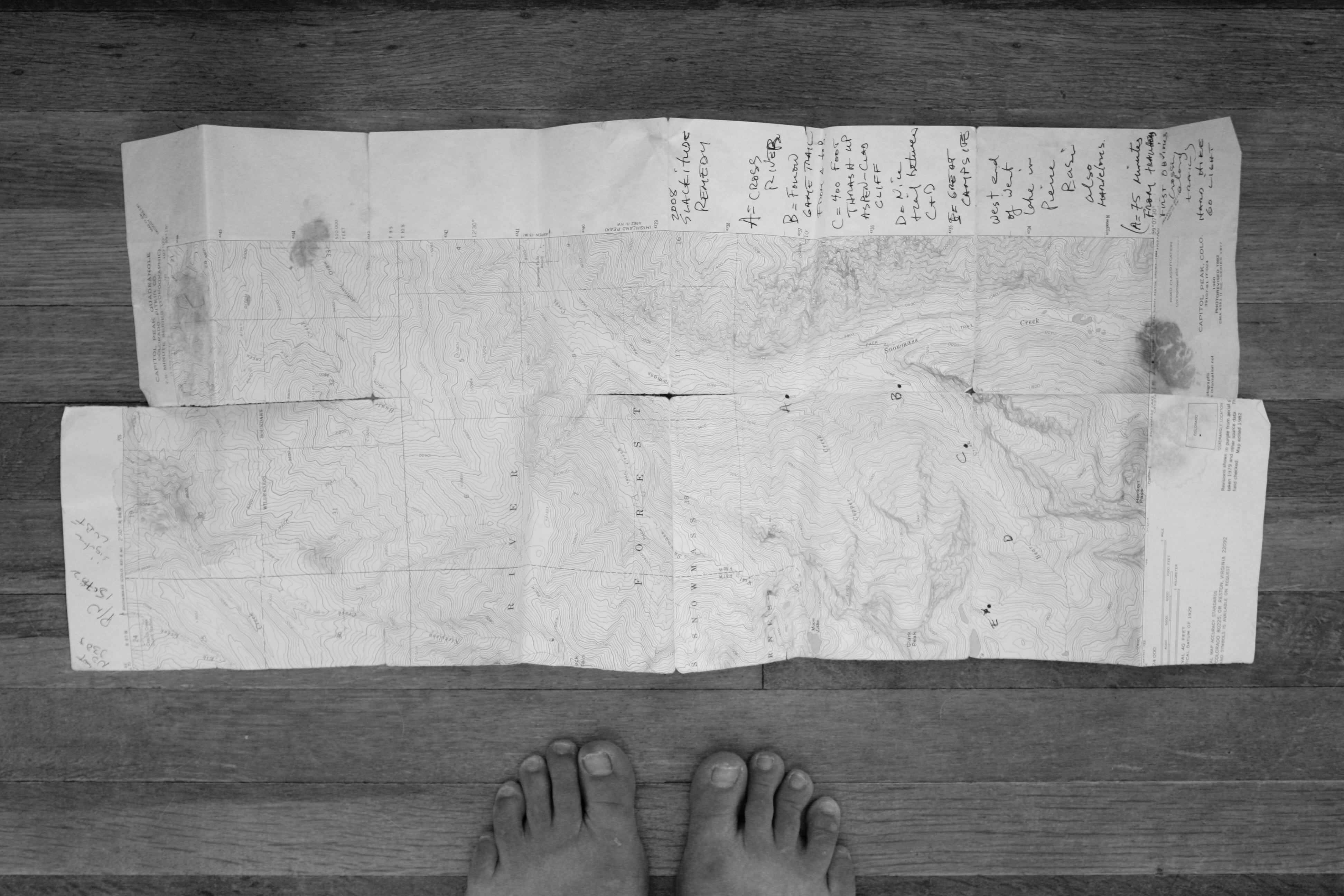

I keep a wooden box on my bedside table.

I keep a wooden box on my bedside table.