The Goose Pond Fish and Wildlife Area, a patch of restored prairie and wetland in southwestern Indiana, is a a favorite stopover for migratory birds and itinerant birders. On January 3, while driving the grid of ruler-straight county roads around the wetland, a birder saw an unmistakable large, white shape: it was a whooping crane, one of the most endangered birds in North America, and it appeared to have been shot dead with a high-powered rifle.

The birder, who happened to be a volunteer with the International Crane Foundation (ICF) in Baraboo, Wisconsin, reported the find to state wildlife officials. The investigation is now in the hands of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the crane’s five-foot-tall carcass is under examination at the National Fish and Wildlife Forensics Laboratory in southern Oregon. For the scientists and conservationists who have spent decades trying to coax whooper populations back to self-sustaining numbers, the news of the shooting was crushingly familiar: 33 whooping cranes have been shot and killed in the United States since the year 2000, according to records obtained by Lizzie Condon of ICF. That’s a huge toll on a species with only about 440 free-roaming members.

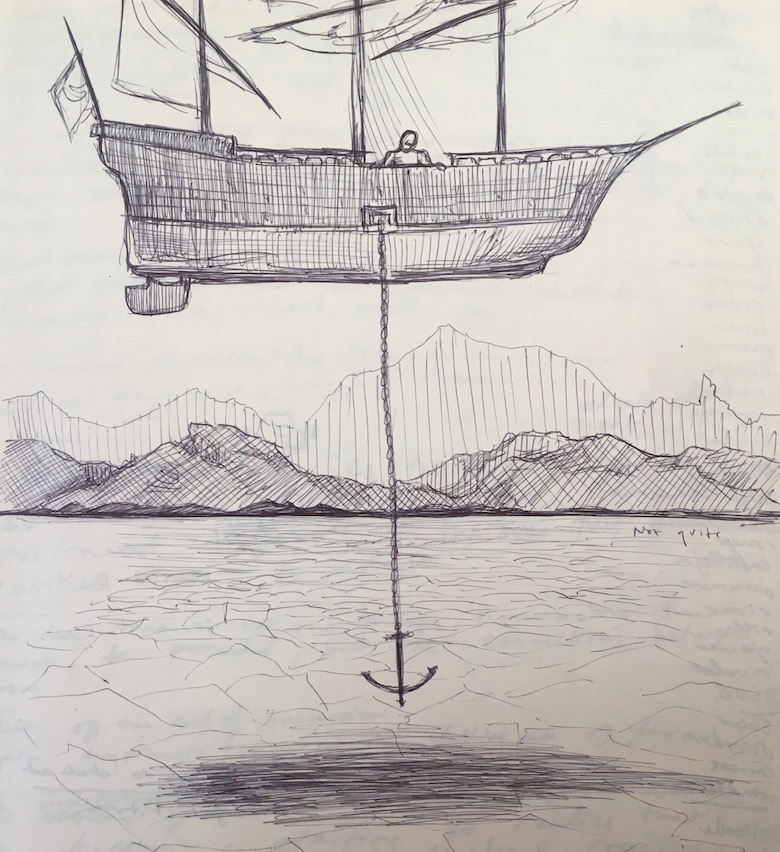

Perhaps 500 yards from my door—up an icy, winding driveway, a short way down a gravel road, beyond barbed wire fences and snow-skirffed pastures and the wind-twisted trunks of piñon and juniper trees—is a barn that shelters two sailboats in the middle of the Colorado desert. I first spotted them on a walk and stopped to stare. The nearest large reservoir is more than two hours away from the house I am borrowing here; the ocean, more than 16 hours away.

Perhaps 500 yards from my door—up an icy, winding driveway, a short way down a gravel road, beyond barbed wire fences and snow-skirffed pastures and the wind-twisted trunks of piñon and juniper trees—is a barn that shelters two sailboats in the middle of the Colorado desert. I first spotted them on a walk and stopped to stare. The nearest large reservoir is more than two hours away from the house I am borrowing here; the ocean, more than 16 hours away.

Since last week, we’ve been watching the weather forecast with something that’s almost joy, but won’t quite let itself be. Often, the weekly report has a beaded string of sunshines, with different ways to describe them. Abundant sunshine. Plenty of sun. Hot. Sometimes, there are clouds. But even when the slot machine lineup of my weather app has a series of rainy days, I’ve learned to wait until I see the silver falling. Ever optimistic, the forecast will show those lucky rainstorms even when the chance of rain is as low as 10 percent.

Since last week, we’ve been watching the weather forecast with something that’s almost joy, but won’t quite let itself be. Often, the weekly report has a beaded string of sunshines, with different ways to describe them. Abundant sunshine. Plenty of sun. Hot. Sometimes, there are clouds. But even when the slot machine lineup of my weather app has a series of rainy days, I’ve learned to wait until I see the silver falling. Ever optimistic, the forecast will show those lucky rainstorms even when the chance of rain is as low as 10 percent.