I had dinner the other night with, among others, a graphic designer. He said he liked looking at contemporary photographs but to be honest, he didn’t know why he liked looking at them. He knew they were better than snapshots, he said, but he didn’t know why they were.

I had dinner the other night with, among others, a graphic designer. He said he liked looking at contemporary photographs but to be honest, he didn’t know why he liked looking at them. He knew they were better than snapshots, he said, but he didn’t know why they were.

I’m certainly the last person to have an answer to that. But I remembered this guest post by Steve Smith, one of those contemporary photographers whose pictures look like somebody just sort of took them — no moody lighting, no startling contrasts, no obvious lines, just black and white pictures of people doing stuff. When I ran Smith’s post, I was most interested in the stories behind the pictures because that’s the kind of person I am, a story-person. And Smith graciously complied with a story that is sweet and surprising, and writing that’s direct and clean and personal. But after my friend the graphic designer asked his question, I went back and looked at Smith’s photos again.

I recommend you do this too. I hadn’t seen how much was going on in them, how they seem mundane and still, but how full of movement they are. Every single person in every single photo is intent on being his or her very own self, going on his or her own private trajectory. You know what every single one of them is thinking. You could write thought-balloons over their heads. You know these people.

But also you don’t understand them. And you have a million questions. Why are the two listening women dressed alike, with their satchels uncomfortably across their fronts? How did the guy hurt his hand? And what’s under his other arm? He’s talking friendly but the listening woman looks skeptical. Why are guys in the back having such fun? Why, in what is clearly a white-peoples’ world, is one of those guys darkish? let alone the black woman sitting by herself? Where are they? Is it an airport? What in heaven’s name is that hot air balloon doing bobbing around up there?

And how does he DO that? Have fun. But it’s a little unsettling.

_____

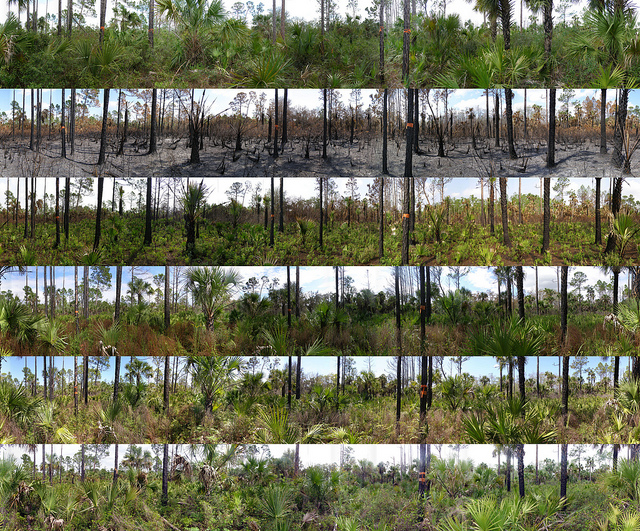

Photo by Steven Smith, not included in the original post.

You know those sounds that slip across the senses until they settle, in the brain, on an association entirely unrelated to their maker? Those sounds that seem to almost synesthetically transform one thing into another? The way noise can be brilliant, or color evokes flavor, or a smell touches old dreams?

You know those sounds that slip across the senses until they settle, in the brain, on an association entirely unrelated to their maker? Those sounds that seem to almost synesthetically transform one thing into another? The way noise can be brilliant, or color evokes flavor, or a smell touches old dreams?

Last week, according to some real news, Earth got a wave hello from far away, from some-3-billion-year-old vibrations that were set off when two black holes smashed into each other. (Really? There’s not room for both of you up there?) According to the New York Times, the collision—reported by the

Last week, according to some real news, Earth got a wave hello from far away, from some-3-billion-year-old vibrations that were set off when two black holes smashed into each other. (Really? There’s not room for both of you up there?) According to the New York Times, the collision—reported by the