This post ran originally in November of 2014, about excavating the desk of a prominent ice researcher at a small camp in Greenland. The researcher, Konrad Steffen, appears alongside Al Gore in the film and book “An Inconvenient Sequel,” which just released. With record high temperatures sweeping the country, enjoy some ice and snow.

Earlier this month, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change came out with an even firmer stance on current environmental affairs, including reams of new data from more scientists saying, basically, news is not good. The New York Times called it “the starkest warning yet.” Little new was revealed in the report, rather it deepened the empirical resolve that changes we are now witness to are the tip of an ever-growing iceberg.

Earlier this month, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change came out with an even firmer stance on current environmental affairs, including reams of new data from more scientists saying, basically, news is not good. The New York Times called it “the starkest warning yet.” Little new was revealed in the report, rather it deepened the empirical resolve that changes we are now witness to are the tip of an ever-growing iceberg.

The findings of the IPCC are not numbers invented out of black boxes. They come from the ground, from sensors, from live people getting eye to eye with the changes that faraway news media eventually pick up.

In May of 2010, I had the back-breaking pleasure of excavating the desk of IPCC cryosphere author Konrad Steffen. Using a shovel, I dug through hard-packed snow to get to his desk and see what he’d been up to.

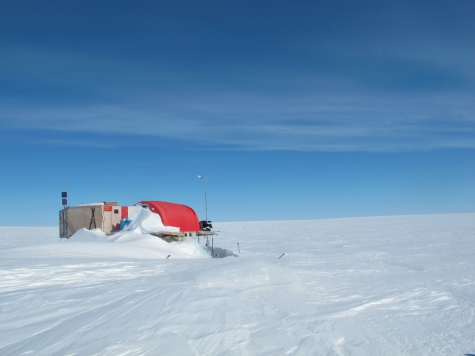

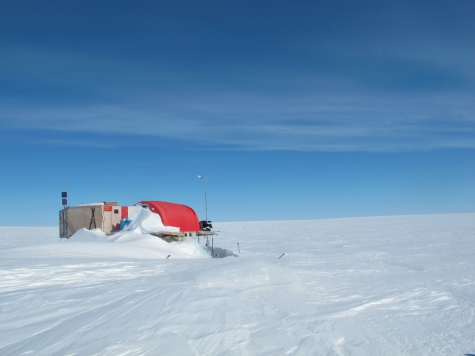

One of the first to land that spring at the small research station of Swiss Camp on the Greenland Ice Sheet, I had arrived with a chaos scientist and climate researcher, Jose Rial, from the University of North Carolina. We were dropped off by ski plane, finding camp crippled by incredible storms that winter, the kitchen tent popped open, snow poured in. Steffen’s office in another tent had turned into a haven of snowdrifts. All six snowmobiles had tumbled to the ice, and would take a few days of hard digging to get out. Once dug out and repaired by Steffen, the snowmobiles would be used to check arrays of remote sensing sites focused on the temperature, movement, and the rise and fall of Greenland’s ice.

A long way from that, I was just starting into Steffen’s desk. The door had creaked open over the winter, and snow drifts covered everything. This wasn’t the kind of snow you’d shovel off a sidewalk. As dry and packed as gypsum, it was easiest broken off in big chunks, shovel wedged to crack off blocks to carry outside. Ghosts shapes had gathered on everything, the ceiling hung with eerie stalactites, fine snow crystals clinging to each other like feather down.

Steffen, Zurich-born and now working out of the University of Colorado, Boulder, is one of the more sought-after voices in cryopshere research. He’d spent thirty-five consecutive seasons on polar ice and overwintered twice in a tent. When he began his studies in the 1960s and 70s, the world’s great ice sheets were thought of as immobile. Glaciers might move, but the big ice was fixed. During his career, that turned out to be false, and Steffen’s own measurements revealed that on one warm summer day, the entire Greenland Ice Sheet will speed up. Meltwater lakes draining suddenly down to bedrock beneath the ice lubricate the process, and he now sees this vast white expanse as highly mobile and easily influenced. Swiss Camp, built in the early 90s, is moving a few feet per day, over decades surfing up and down on oceanic waves as the ice sheet flows toward the coast and ultimately into the sea.

On his desk, I dug down to electronic equipment, sensors in various states of construction and repair. I saw whatever Steffen had been working on when he last evacuated his camp, taking the first weather window, his desk left in mid-action, pencils sharpened to stubs. With an over-mitt, I picked up a candle burned halfway down, imagining Steffen sitting here writing his late-night papers, his findings adding to the weight of the IPCC not from a four-walled office, but out here on the ice.

I found under a drift a bottle of Johnny Walker Black Label, a Scotch whiskey Steffen had marked with his name. Being alcohol, it was the one thing not frozen. I uncapped it and took a swig, warming my insides from the scientist whose desk I was exhuming. What IPCC researcher, I wondered, does not have a bottle somewhere nearby? Knowing what he knows, how the big machine of the earth is shifting beneath us, around us, I’d take more than one swig.

When Steffen’s plane landed at the edge of camp, more of the crew climbed out. Gear was unloaded quickly, pilot chasing windows in blustering polar weather.

As the plane flew off, Rial showed Steffen the damage that we’d found, camp tents partially wrecked, snowmobiles gone. Steffen had a lean-boned face, a healthy-looking character with a thick, neatly-trimmed beard. His beard iced up as soon as he emerged into the cold. Rial led him around, pointing out solar panels that had blown off, and a weather station bent over by winter storms.

In one swift move, Steffen lit a cigarette in the crook of an upraised arm. Holding it in his teeth, confidently sucking to keep the thing lit in the wind, he said, “I’ve seen worse.”

Photos by Craig Childs

There’s an unclaimed patch of ground right next to our driveway, the planting strip between the sidewalk and the street. Over the years it’s been filled with many things. Weeds, mostly. Orange poppies. Maroon-colored amaranth that toss confetti seeds across the sidewalk. Weeds, again.

There’s an unclaimed patch of ground right next to our driveway, the planting strip between the sidewalk and the street. Over the years it’s been filled with many things. Weeds, mostly. Orange poppies. Maroon-colored amaranth that toss confetti seeds across the sidewalk. Weeds, again.