The Last Word

The Last Word

November 20-24, 2017

Sarah changed her landscape, and finds herself changed. I never meant to be one of those people who would trade redrock bones of desert and mountain crags and the velvet nakedness of tundra for the claustrophobic press of forest. For a place so green and eager to grow that if you sit still too long you’ll be mossed and brambled over, just another soft shapeless lump at the toes of giants.

Craig looks for pockets of acoustic delight wherever he travels. I move through the city the same way I move through the desert, looking for shaded alcoves that might hold rock art, hissing or clucking my tongue to hear the sound bounce back.

Emma eats an Impossible Burger with Charles Mann. For lunch, Mann and I dined at Farmers & Distillers on Massachusetts Ave, one of the early adopters of the Impossible Burger, a wheat-based veggie burger that includes heme produced by genetically engineered yeast. It tastes not exactly like beef but light-years more like beef than any veggie burger I have ever tried.

Thursday was Thanksgiving in the US, and the People of LWON talk about gratitude. It’s not payment for goods delivered in hope of getting more, but a sentiment, a weightless emotion, a thank you. Whatever it is, it goes out and not in.

On Friday, we rehash our Thanksgiving memories. Some people associate scents like baking pie crusts and buttery sweet potatoes with the fall holidays. That would be nice. My scent memory is no less powerful, though not quite as pleasing. Giblets.

*

Image by Sarah Gilman

Craig

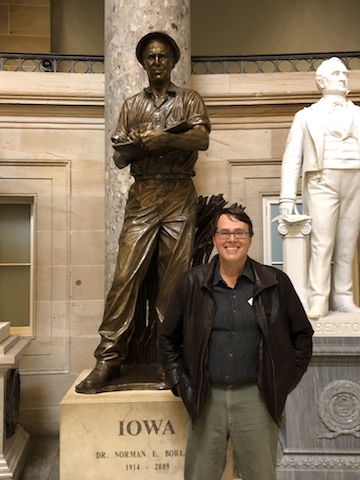

Craig If you are planning a huge, calorie-dense feast for dinner later this week, you might want to take a moment to thank a man you’ve likely never heard of—a man whose scientific breakthroughs in agriculture made food cheaper and more plentiful around the world.

If you are planning a huge, calorie-dense feast for dinner later this week, you might want to take a moment to thank a man you’ve likely never heard of—a man whose scientific breakthroughs in agriculture made food cheaper and more plentiful around the world.  In caves and rock walls of the southern Utah desert, pictographs have been painted, added to the backs of clamshell-shaped sandstone enclosures. Many are noted to have acoustic properties, meaning these ancient, Indigenous images seem to be correlated with the way sound reflects around them. I’ve spoken in a normal voice back and forth from one sheltered rock art panel to another an eighth of a mile downcanyon. The way sound spreads and is refocused, we could hear each other’s every word.

In caves and rock walls of the southern Utah desert, pictographs have been painted, added to the backs of clamshell-shaped sandstone enclosures. Many are noted to have acoustic properties, meaning these ancient, Indigenous images seem to be correlated with the way sound reflects around them. I’ve spoken in a normal voice back and forth from one sheltered rock art panel to another an eighth of a mile downcanyon. The way sound spreads and is refocused, we could hear each other’s every word. I never meant for this to happen.

I never meant for this to happen. There is no roadmap for confronting a neighbor in the grocery store about a sexual assault that happened twenty years ago.

There is no roadmap for confronting a neighbor in the grocery store about a sexual assault that happened twenty years ago.