UPDATE, 10/27/2020: This post is about, among other things, Peter Ganz, a German philologist with an unlikely personal history. One of his sons, Adam, just wrote telling me about a centenary at Oxford University that celebrates Peter’s accomplishments. I thought you might like to know. I mean, the man left Buchenwald, then helped spy on German bomb physicists, then ended up as a medievalist at Oxford — not your normal life trajectory.

This first appeared in December 19, 2013. I run it again now because I’ve been reading David C. Cassidy’s new book, Farm Hall and the German Atomic Project of World War II, subtitled, “A Dramatic History.” Cassidy is an historian of physics, so the “history” part of the subtitle is not unexpected. But he also wrote a play — the “dramatic” part — about a subject which for no good reason I’m obsessed with and which is explained below. Cassidy’s dramatic history is a play followed by the nearly everything Cassidy knows about the subject, which is considerable: so, a play with its historical context. It’s an unusual and charming thing for an academic historian to do. The book isn’t making me any less obsessed.

____________

About a month ago, I wrote a review of a play by David C. Cassidy about Farm Hall. Farm Hall was the English country house in which the British government, just after World War II, sequestered the German nuclear scientists they’d kidnapped. The scientists’ rooms were bugged, and their conversation was recorded and transcribed by listeners. The result was a transcript which had fairly cried aloud to be turned into a play. David Cassidy, among others, did. I reviewed it and afterward, heard from Dr. Oliver Dearlove, pediatric anaesthetist (retired) who lives in the UK.

Oliver: Very interested to read your review in Nature about the Farm Hall play. I remember 2010, Adam Ganz did another play about Farm Hall on Radio 4. In the e-book of the Farm Hall transcripts, one of the listeners was a Peter Ganz. I suspect/wonder if he was Adam’s father.

Oliver: Very interested to read your review in Nature about the Farm Hall play. I remember 2010, Adam Ganz did another play about Farm Hall on Radio 4. In the e-book of the Farm Hall transcripts, one of the listeners was a Peter Ganz. I suspect/wonder if he was Adam’s father.

Ann: How very extremely interesting. I’ve never heard of either one. With your permission, I’ll forward your question to David Cassidy, who not only wrote the play I reviewed, but is also an historian of physics who wrote a splendid introduction to one publication of the transcripts.

Oliver: Thank you for your speedy reply, dear madam. Please send to Cassidy the following version of my question which I have tarted up in true scientific fashion.

Tarted-up official question was sent immediately to Cassidy.

David Cassidy: Dr. Dearlove, I am the author of the play Ann Finkbeiner reviewed, and I thank you for the reference to the Radio 4 play. Do you happen to know how I might locate Adam Ganz?

Oliver: I am sorry for not replying sooner. Adam Ganz is to be found here. His play is listed on the Radio 4 website but as far as I can discern it is unavailable for playback. Do you think that A. Ganz is related as I suspect to P. Ganz?

David: I’ll try to get in touch with A. Ganz. It’s a shame that his play isn’t available.

A short interval occurs before emails resume.

Ann: But you CAN, you can, you can get Ganz’s play. My work has been going badly so I’ve clicked around on the internet. And the Radio 4 link really is dead but there’s another secret one. This is the best thing I’ve done all day.

Oliver: We are having an excited Adam Ganz experience via the internet.

David: A jolly good find, indeed!

Ann: And here’s Peter Ganz! Or rather, his obituary.

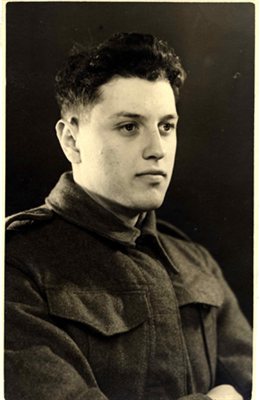

And what a life Peter Ganz had. He was born in Mainz, Germany to a Jewish family that became Lutheran. But converting didn’t help the family during Kristallnacht and Peter’s grandfather, Adam’s great-grandfather, was killed at Auschwitz. Peter himself was sent to Buchenwald but some reason, was released. He fled to England, went to university, and became a philologist at Oxford – specialty, medieval German; sub-specialty, Jacob Grimm. But while he was still in college, he was put in an internment camp as an enemy alien, and a little later, was sent to Farm Hall as a listener.

And what a life Peter Ganz had. He was born in Mainz, Germany to a Jewish family that became Lutheran. But converting didn’t help the family during Kristallnacht and Peter’s grandfather, Adam’s great-grandfather, was killed at Auschwitz. Peter himself was sent to Buchenwald but some reason, was released. He fled to England, went to university, and became a philologist at Oxford – specialty, medieval German; sub-specialty, Jacob Grimm. But while he was still in college, he was put in an internment camp as an enemy alien, and a little later, was sent to Farm Hall as a listener.

Oliver: This is clearly the father even from the internal evidence in the play – one of the characters specifically mentions philology and Grimm. The names of all the listeners seem to be on p. 275 of Helen Fry’s book, The M Room. And there’s Peter Ganz, on the list.

Ann: And on p. 166, here he is, being transferred to Farm Hall. Amazing what you can do on Amazon with a Look-Inside.

Oliver: Yeah the American Look-Inside must be bigger better all round than the British one – all I got was an index.

David: My goodness, you two have been busy. This is quite a treasure trove. As I told you, I wrote to Adam Ganz, and he’s just written back.

Adam Ganz: Yes, Professor Cassidy, my father was one of the listeners at Farm Hall. His supervisor at college was the language consultant to Enigma. He found the work extremely interesting but he spoke little about it. I talked with him a little toward the end of his life. Of the German scientists, he liked and respected Otto Hahn very much, he admired Max van Laue, he really didn’t like von Weizsacker.

David: I don’t think anyone liked von Weizsacker.

Nevertheless, Adam Ganz’s play, Nuclear Reactions, is kind to von Weizsacker. In fact, it’s kind to all the German scientists, to all these famous physicists who’d been trying and failing to build an atomic bomb for Nazi Germany. They are heard clearly in the transcripts to be creating an alternate version of the truth — a lie, in fact — in which they hadn’t built the atomic bomb because they wanted to work on a reactor for generating energy in peacetime.

At the end of the transcripts, they were released from Farm Hall and allowed to return to their jobs and universities. But the transcripts are reality and reality is of course messy – no single right interpretation, no one clear storyline, no moral, none of the meaning that a playwright imposes.

Adam’s take on the incoherent transcripts is that the Germans were allowed their lie; that Britain in its own interests sent them back to Göttingen to help post-war Germany rebuild its science and industry; that perhaps Germany needed “normal Germans who wouldn’t build the bomb,” the play says. “Germany doesn’t need any more criminals, it needs heroes.”

And it’s true that many of them, von Weizsaecker included, later signed the Göttingen Declaration, warning against the proliferation of nuclear weapons and promising that “none of the undersigned are prepared to participate in the creation, testing or deployment of any type of nuclear weapon.”

§

The email conversation moved on to other subjects but I was still interested in Adam’s kindness to the would-be bomb builders.

At one time, Adam went back to Mainz and visited the cemetery where the Ganz family was buried. The cemetery wasn’t old; each Mainz family had bought plots with its dynasty in mind, so the headstones had a name or two at the top and space left for the names of the coming generations. But it was a German Jewish cemetery, and the Jews fled or were killed. So the headstones are blank.

Adam wrote an essay, “On Speaking and Silence and the Refusal of Historical Accuracy.” It was about the cemetery, and about finding documents his great-grandfather had left behind before Auschwitz, and about trying to piece together his family history; and then about wondering what to do once he’d exhausted the documents, once he’d exhausted history. Fiction, he wrote, “can help us to recreate the grandparents we needed and tell the terrible story of their eradication, and how through us, something somehow floated to safety. Like writers before us, we can simply make it up.”

So Adam made the play’s narrator a German philologist with a fondness for Grimm’s fairy tales — someone who could sound very much like Peter Ganz. At the play’s end, with the nuclear scientists all back in the directorships of their scientific institutes, Adam’s narrator/Peter says that Grimm collected many stories: some like Hansel and Gretel we remember; and some like The Jew Amongst Thorns, we pretend to forget. “We pretended they were heroes,” the narrator says, “and sent them back to Göttingen, and you know the most amazing thing? That’s what they turned into.”

§

In his play, Adam tells one of the Grimm fairy tales, The Shroud. A mother has a little boy whom she loves dearly. But the little boy gets sick, and dies. And mother weeps and never stops weeping. One night the boy comes to her in the little white shroud in which he was laid in his coffin, and asks her to stop crying because his shroud is wet with all her tears and it won’t dry. So the mother stopped crying.

“And the next night the boy came again, holding a little light in his hands and said Look, Mother, my shroud is nearly dry and I can rest in my grave. The mother gave her sorrow to God’s keeping and bore it quietly and the child came no more and slept in his little bed beneath the earth.”

__________

Note on historical accuracy: the facts here are right; but the conversations are partly a reconstruction – a lie – from actual emails, organized and edited so that they make sense as a story. It’s a process related to what Adam Ganz was doing, but not the same thing at all.

__________

Adam Ganz has written two other, related plays, Listening to the Generals, about a similar British bugging of a country house, this one full of German generals; and the Gestapo Minutes, about Mainz during the war.

___________

Photo of Peter Ganz through the kindness and courtesy of Adam Ganz. Photo of the old (not the new) Jewish cemetery at Mainz by Ralf Mauer, via Wikimedia

Last month I published a story in Nature about the sad story of the axolotl. It’s a tragic tale of an incredibly bizarre creature looking at extinction in the wild. Of the many odd attributes of the axolotl – ability to regrow limbs, giant cells, laughably big genome – the one that always gets mentioned by science writers is their neoteny.

Last month I published a story in Nature about the sad story of the axolotl. It’s a tragic tale of an incredibly bizarre creature looking at extinction in the wild. Of the many odd attributes of the axolotl – ability to regrow limbs, giant cells, laughably big genome – the one that always gets mentioned by science writers is their neoteny.

Happy 12th month, readers! Lurch with us into December with these fine offerings:

Happy 12th month, readers! Lurch with us into December with these fine offerings:

On Tuesday, I texted my friend Michelle

On Tuesday, I texted my friend Michelle